Scientists may have just found what makes the sun's outer atmosphere, the corona, so inexplicably hot.

For decades, scientists have been struggling to explain why temperatures in the sun's outer atmosphere, the corona, reach mind-boggling temperatures of over 1.8 million degrees Fahrenheit (one million degrees Celsius). The sun's surface has only about 10,000 degrees F (6,000 degrees C), and with the corona farther away from the source of the heat inside the star, the outer atmosphere should, in fact, be cooler.

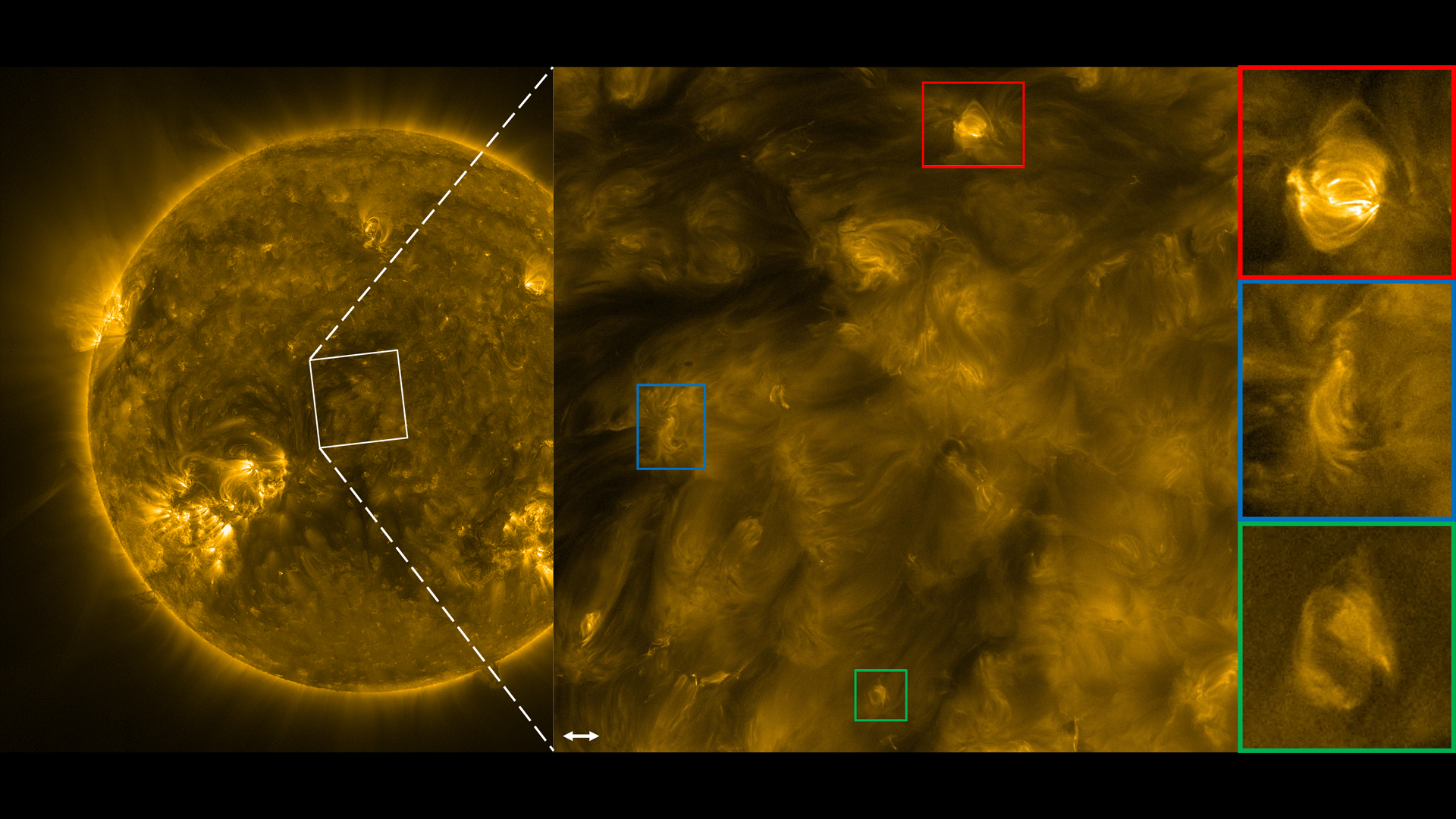

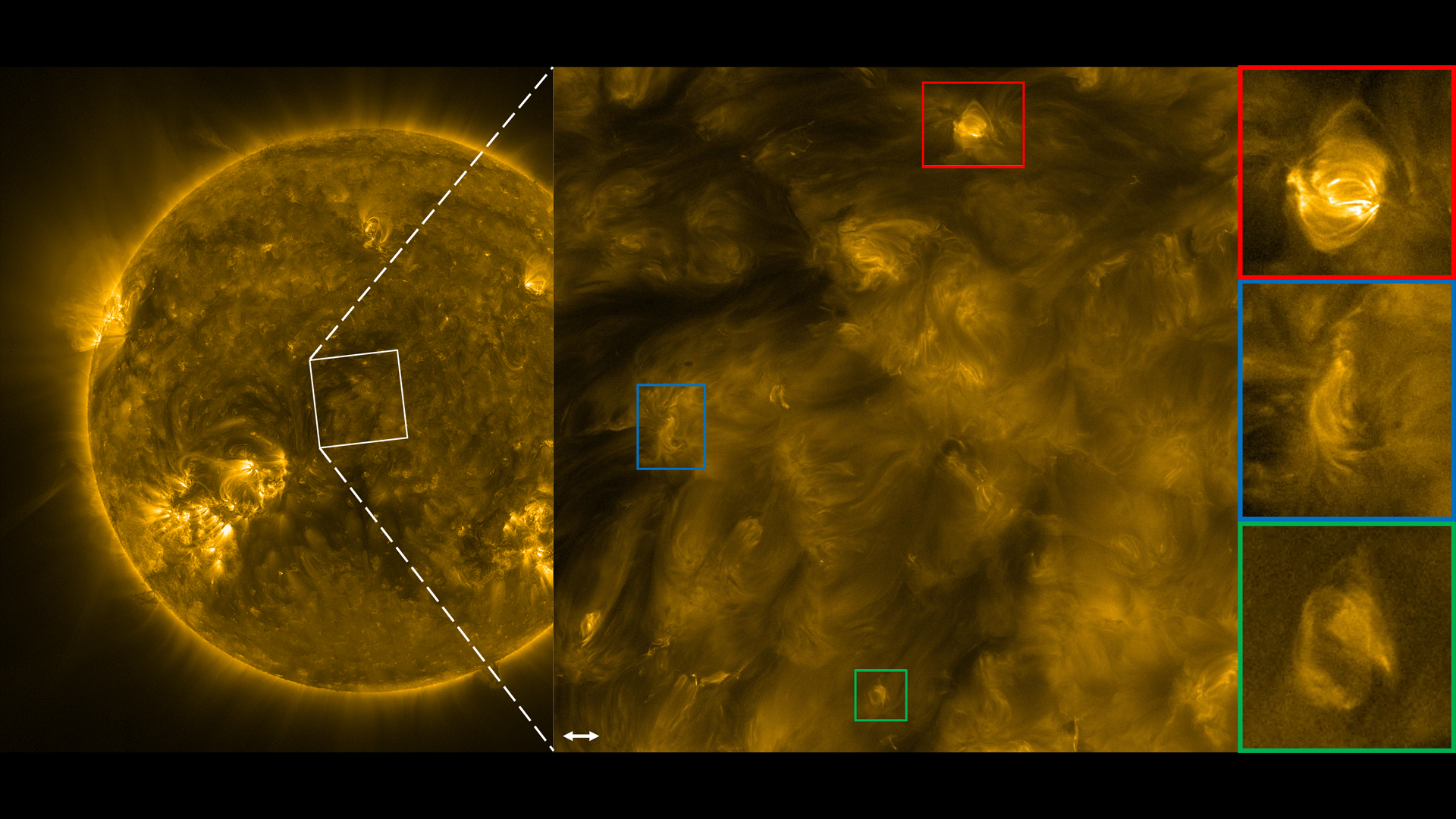

New observations made by the Europe-led Solar Orbiter spacecraft have now provided hints to what might be behind this mysterious heating. Using images taken by the spacecraft's Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI), a camera that detects the high-energy extreme ultraviolet light emitted by the sun, scientists have discovered small-scale fast-moving magnetic waves that whirl on the sun's surface. These fast-oscillating waves produce so much energy, according to latest calculations, that they could explain the coronal heating.

Related: Solar Orbiter spacecraft takes its closest look at the sun

Scientists have previously detected slower magnetic waves, but those didn't seem to produce enough energy to explain the enormous temperature difference between the sun's surface and the outer atmosphere.

"Over the past 80 years, astrophysicists have tried to solve this problem and now more and more evidence is emerging that the corona can be heated by magnetic waves," Tom Van Doorsselaere, a professor of plasma physics at the Catholic University of Leuven in Belgium and one of the authors of the new study, said in a statement.

The newly discovered structures can be seen in a video sequence captured by the EUI instrument in October last year. Each of the magnetic oscillations, highlighted in blue, green and red rectangles, is less than 6,200 miles (10,000 kilometers) wide. For context, the solar disk measures 864,000 miles (1,392,000 km) in diameter.

Solar Orbiter, launched in February 2020, takes the closest images of the star at the center of our solar system. Although Earth-based telescopes can provide images of the sun in a higher resolution, these telescopes can't study the extreme ultraviolet part of the solar light spectrum. Because these frequencies are filtered out by Earth's atmosphere, ground-based telescopes therefore don't see many of the key phenomena driving the sun's behavior.

Solar Orbiter, which makes regular approaches to less than 48 million miles (77 million km) from the sun (closer than the orbit of the solar system's innermost planet Mercury), doesn't have those issues. In its first images of the sun alone, released in June 2020, Solar Orbiter found other indications of processes that might play a role in the coronal heating mystery.

David Berghmans, the principal investigator of the EUI instrument and solar physicist at the Royal Observatory of Belgium added that the team will now dedicate more time to studying the newly discovered magnetic waves on the sun's surface.

"Since her results indicated a key role for fast oscillations in coronal heating, we will devote much of our attention to the challenge of discovering higher-frequency magnetic waves with EUI," Berghmans said in the statement.

The study was published on Monday, July 24, in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.