Researchers have drilled the deepest-ever sample of rocks from Earth's mantle, penetrating 0.7 mile (1.2 kilometers) in the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, where the seafloor is spreading apart.

At this spot, which is rich in hydrothermal vents, the interactions between mantle rocks and seawater create chemicals that are important for life. Previous efforts to drill into mantle rocks brought to the surface in the deep sea had reached only 659 feet (201 meters) — not deep enough to look for organisms such as heat-loving bacteria that might dwell farther down, said Gordon Southam, a geomicrobiologist at the University of Queensland in Australia and a co-author of a new study describing the core sample.

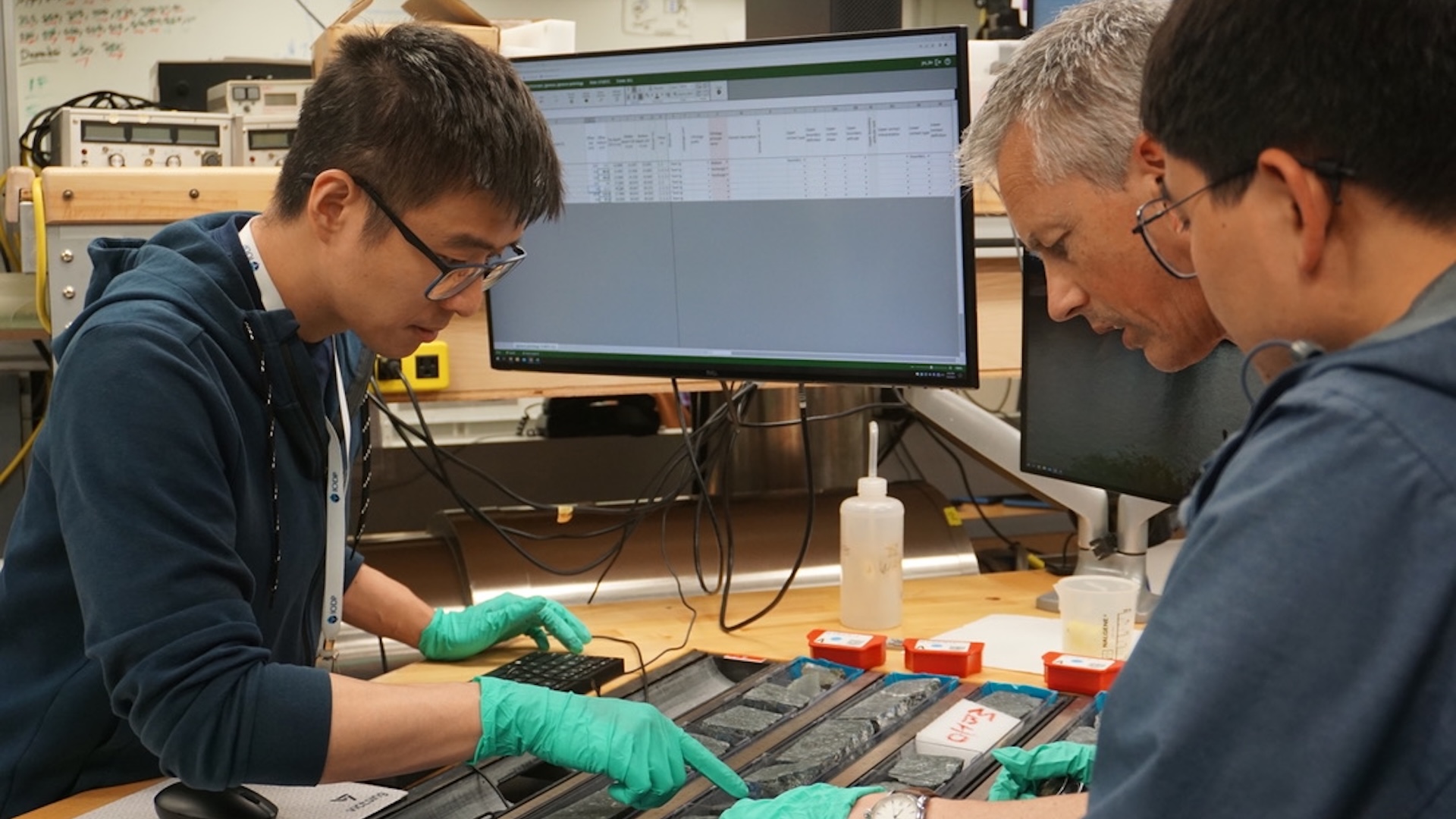

"Every time the drillers recovered another section of deep core, the microbiology team collected samples to culture bacteria to determine the limits of life in this deep subsurface marine ecosystem," Southam wrote in an email to Live Science. "Our ultimate goal is to improve our understanding of the origins of life and to define the potential for life beyond Earth."

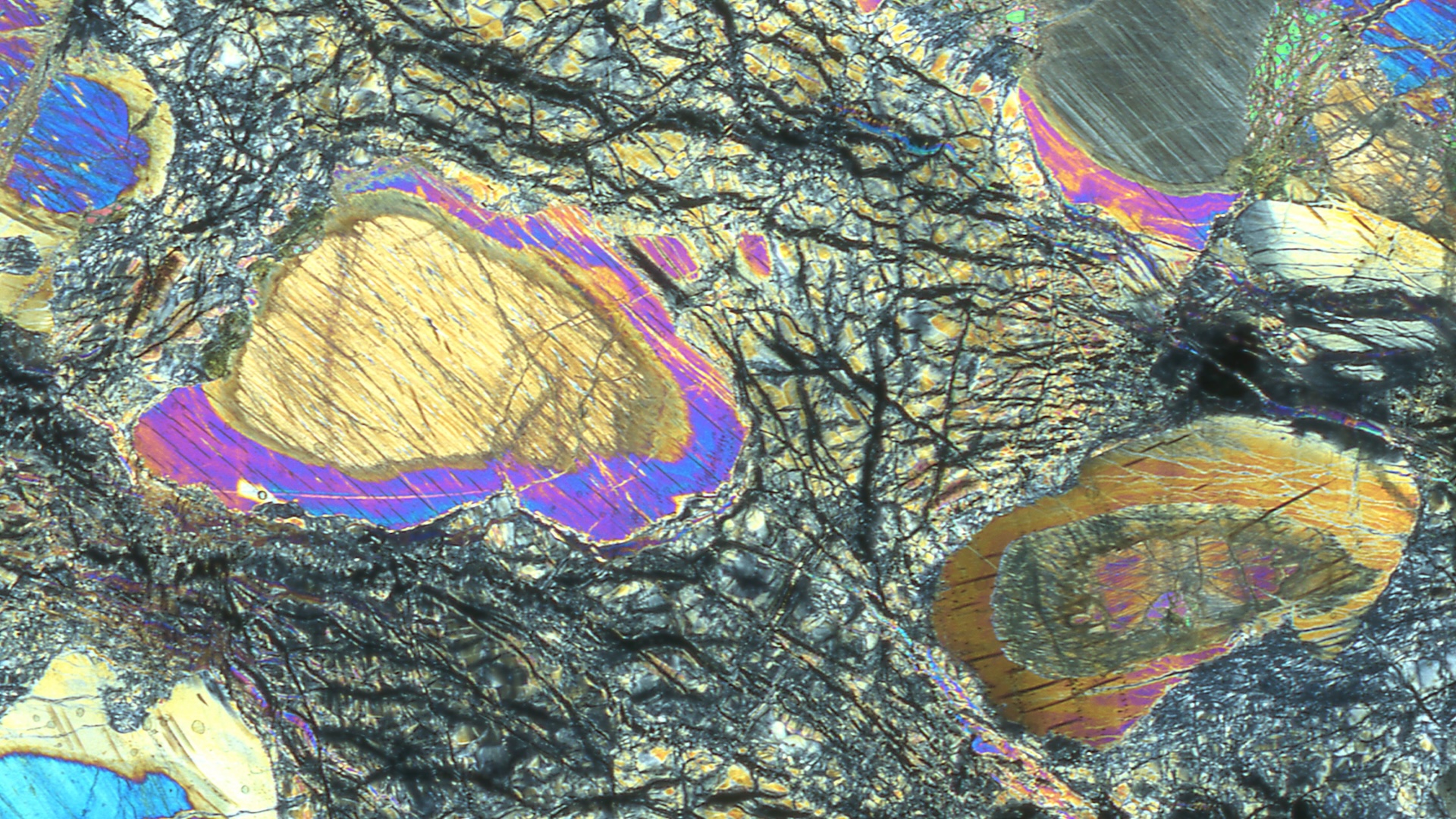

The rock core can also answer questions about the movement of the mantle, said Johan Lissenberg, a geochemist at the University of Cardiff in the U.K. and first author of the study, published today (Aug. 8) in the journal Science. "We know from the rocks that erupt in oceanic volcanoes that the mantle has a lot of different 'flavors,'" Lissenberg told Live Science. These "flavors" are varying rock compositions that come from the recycling of tectonic plates into Earth's interior.

With the new mantle sample, "we can really try to see what flavors have we got and on what scale do they vary," Lissenberg said, "and then reconstruct how those different bits of the mantle melted and then how they migrated towards the surface."

So far, the team has found that rather than traveling vertically, melts seem to move obliquely, traveling in a diagonal, inclined path toward the surface, Lissenberg said.

The core was drilled by the International Ocean Discovery Program in 2023. Researchers aboard the JOIDES Resolution research vessel drilled into the Atlantic Massif, a portion of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge where the ocean floor is pulling apart and mantle rocks are rising to the surface. The spot drilled was near the "Lost City," a hydrothermal vent field crowded with beehive- and tower-shaped structures that release methane and hydrogen into the ocean. Numerous microorganisms live off these molecules, supporting communities of small invertebrates like snails and tubeworms.

Mantle rock is fragile and tends to fall apart, jamming drill bits, Lissenberg said, but the team was remarkably lucky.

"For some reason, the mantle rocks in our site drilled like a dream," he said. "It was absolutely incredible to see."

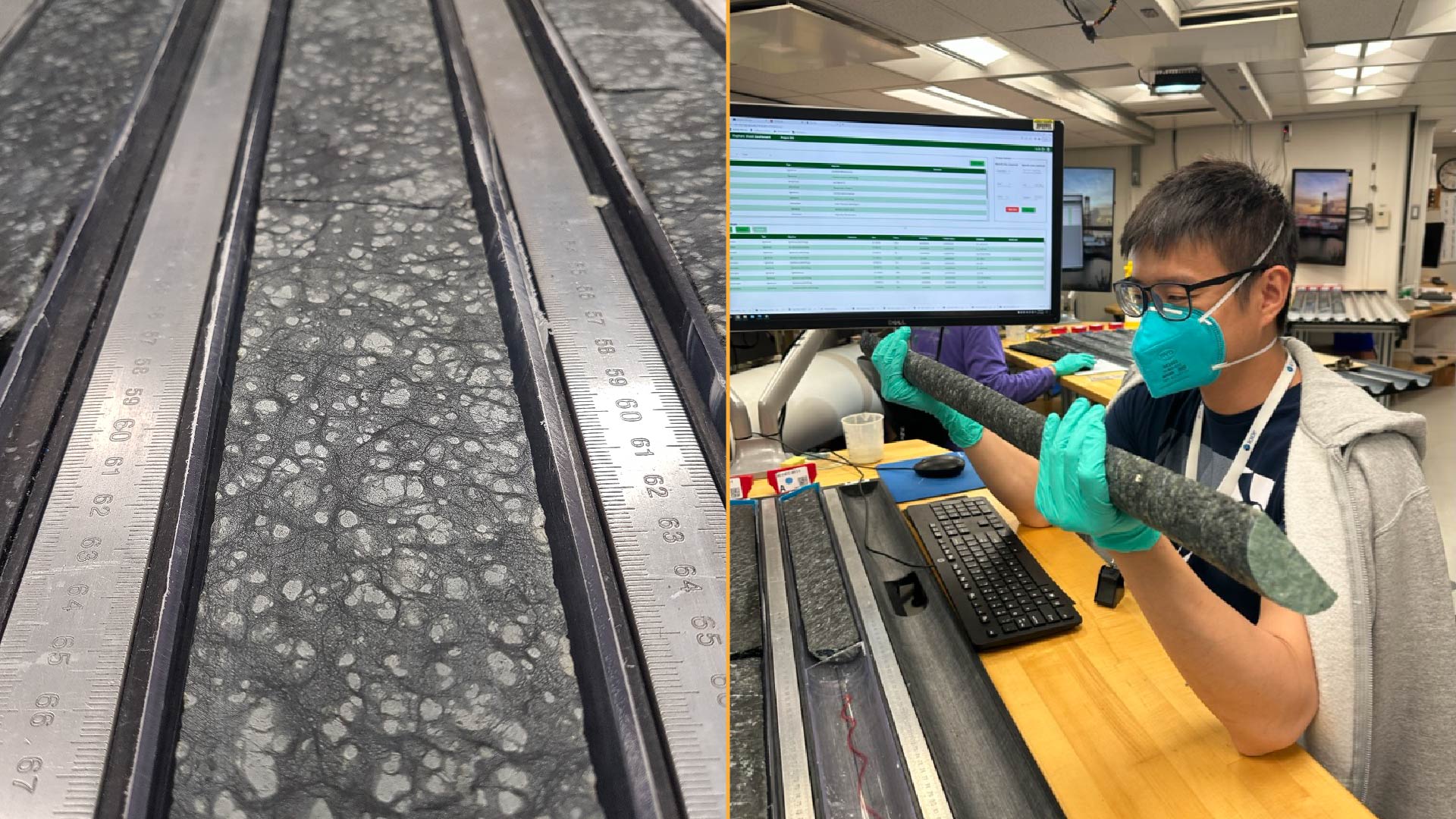

The team began pulling intact sections of up to 16.4 feet (5 m) from the hole. In total, they retrieved a continuous record of more than 70% of the 0.7-mile core.

"We collected so many more samples than we had been expecting that we had already consumed many of our sample collection supplies by halfway through the expedition," study co-author William Brazelton, a microbiologist at the University of Utah, wrote in a statement emailed to Live Science. The microbiology team was smashing rocks with sledgehammers nearly 24 hours a day for the two-month drilling project, he added.

"The nearly continuous recovery down to 1.2 km provides an excellent opportunity to document the relationships among microbial diversity, abundance, and activity with depth and temperature, including temperatures approaching the limit for life," Brazelton said.