The typical reaction to learning about how people have lost money to a con artist is “how could anyone be so gullible?” But it’s the wrong question. Fraudsters fool even the most clever and admired experts by playing on their psychological vulnerabilities.

News of multi-million and even multi-billion dollar deceptions keep rolling in. Sam Bankman-Fried, the founder of FTX (a Bahamas-based cryptocurrency exchange), attracted an A-list of investors and celebrities. Among his investors were some of the most respected names in finance. The list of celebrities who endorsed him — Tom Brady, Steph Curry, Naomi Osaka, Larry David, Kevin O’Leary — was just as impressive.

A billionaire many times over, Bankman-Fried’s empire collapsed in November 2022. Now FTX is a bankrupt company and Bankman-Fried is awaiting trial on multiple charges related to fraud.

The Bankman-Fried story may not be so different from Elizabeth Holmes’s. At the height of her success, Holmes was declared the youngest self-made female billionaire. According to Forbes, her net value was a staggering $4.5 billion, based on her 50% stake in the now-defunct company Theranos. The line of investors in Theranos represented some of the world’s best-known names, including Rupert Murdoch and the Walton family. Recently, a court filing claimed Holmes bought a one-way ticket to Mexico in an attempt to flee the US after her conviction on fraud charges in 2022.

How did Holmes dupe so many experts and well-known people, as Bankman-Fried is also accused of? Like most skilled fraudsters, it is claimed they used their victims’ emotional needs against them.

No one is immune

The stereotypical image of fraud victims is that they are naïve and older. Data on fraud victims presents a very different picture, however, one that is far more nuanced. Depending on the type of fraud that researchers examine, it’s clear that sophisticated, well-educated and young people are all vulnerable to scams. Fraudsters often target a particular demographic – the well-off and well-known are targeted with scams bespoke to them.

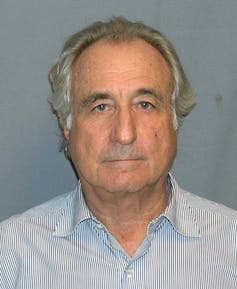

Research has also found that overconfidence is an important factor in fraud vulnerability. People who are high achievers in one domain (for example, military expertise) may overestimate their ability to perform due diligence in a separate field (medical lab equipment). This could, for example, help explain how Bernie Madoff was able to scam wealthy, well-educated professional people who are not necessarily financial experts.

In our research, we have found that people often feel confident in their ability to detect a scam. In a series of experiments that investigated why people engage with materials that are obviously scams – such as letters apparently notifying the person of lottery winnings – we found a subgroup of people who said such letters were probably a scam but would contact the scammers to see for sure, then still back out without any losses.

A typical scam starts by exposing a victim to the fraudster’s pitch, which is designed to evoke strong emotions such as fear. Then fraudsters use persuasion tactics such as commitment (making people feel obligated to follow through on a pledge), authority (police), scarcity (time pressure), and “social proof” to engage their targets.

Social proof is a term coined by psychologist Robert Cialdini to explain the way consumers will adapt their behaviour in response to what other people are doing. Celebrity social proof can be especially powerful. Famous people may not fully understand the technology yet still convey confidence in a product or service’s effectiveness.

In October 2022, Kim Kardashian agreed to pay a $1.26 million (£1 million) settlement to the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in relation to claims she failed to disclose that she had been paid $250,000 for publishing an Instagram post touting the cryptocurrency company EthereumMax. And a recent class action lawsuit named several A-list celebrities (Madonna, Justin Bieber, DJ Khaled, Paris Hilton, Gwyneth Paltrow, Snoop Dogg, Serena Williams and Jimmy Fallon) as part of a fraud case for endorsing luxury brand Bored Ape Yacht Club’s non-fungible token scheme.

New-age fraud

Social media has made it easier for famous people to communicate with their followers, something companies have been quick to monetise. Unfortunately. con artists have too. Celebrities’ credibility is being hijacked, dragging their legions of fans down with them.

Experts and wealthy people may feel that the authority their knowledge or riches gives them acts as a shield. But research shows people who are already comfortable with investing and taking risks are more likely to be approached with illegitimate investment opportunities. They are also more open to these opportunities.

From a scammer’s logistical perspective, it is much easier to defraud a few rich people or organisations than many poor ones. A report by wealth management service Saltus found that people whose net worth is over £3 million are twice as likely to report being a fraud victim, compared with those with a net worth of £250,000-£500,000.

When someone’s reputation is on the line, they might have less incentive to admit being a victim. This could help explain why the US attorney office in San Francisco needed to put a public call out asking for information from Holmes’s victims, and the US Justice Department had to create a similar mechanism for FTX victims.

In our work, we interviewed psychologists who had fallen for scams. Because part of their “brand” is expertise on human behaviour, they feared exposure and humiliation and were disinclined to report the crime or seek help. But their shame only allows the scam to continue and defraud more victims.

We are concerned that social media will only drive more investment scams in the future. So remember, investments that defy financial fundamentals should be approached with extreme caution. Involvement of a third party such as an accountant may help you avoid decisions based on superficial appeal.

Social media may have moved the goalposts, but the classic advice to never assume anything is true without checking for yourself is still worth heeding.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.