Once called “the redwood of the east” with a typical height of more than 100 feet and a diameter up to 10 feet, the American chestnut is a historical icon of Appalachian ecology. Its destruction was also an archetypical North American ecological disaster. But now, amid the rising despair and psychological weight of climate change, citizen scientists are using community conservation to restore an ecology of hope for the trees. Their victories are preserving more than a keystone biological species. They’re saving a living vessel of ancient stories from cultures around the world — including the hidden histories of their own mountain homes.

Among the most significant dietary and economic resources in Appalachia, the chestnut fed a rich sprawl of multiracial agrarian communities, fattening both hogs and children among Kentucky’s poorest families, whose grandparents still recount memories of individually named trees.

“In 1898 my father built a party telephone line five miles long from his store on Wells Creek into Sandy Hook, the County Seat of Elliott County, Kentucky,” reads the account of Curt Davis, collected by the American Chestnut Cooperators’ Foundation.

“He specified in the construction of the line that all poles be chestnut that were seven to eight inches in diameter at the butt and 24 feet long. He knew that there would not be more than one inch decrease in the diameter in 24 linear feet because they grew straight and tall. He also knew that the poles would be uniform and long lasting,” he wrote.

Davis, born in 1910, tells of a land busy with harvesting the timber and fruit of chestnuts — and of the chestnut market news brought by his father’s new party-line telephone.

“I find in my father's 1898 and 1899 ledgers where chestnuts used in bartering at the country stores were traded at $0.12 to $0.15 per gallon, for baking powder at $0.05 a pound,” he said. “Salt at $0.02 a pound….sugar at $0.04 a pound.”

But one day, a rich man in New York brought all that to a crashing end for Appalachia.

In 1876, Samuel Browne Parsons Jr. caused what is often called the greatest ecological disaster in American history when he imported a crop of Japanese and Chinese chestnut trees to sell in the U.S. Parsons was a landscape architect whose father had made a tidy career importing Asian plants. Parsons himself attended Yale and then inherited his dad's business, selling his imported chestnut crop to renowned planners like Frederick Law Olmstead and distributing them throughout America’s parks.

Parsons’ trees, however, were carrying passengers. One was a pathogenic fungus called Cryphonectria parasitica, or chestnut blight. It lay quietly in the Asian trees whose native immunity concealed its threat, but the North American species was highly vulnerable. The blight precipitated an insidious acid in the American chestnut trees, and gnawed grievous cankers into their woody trunks. Weeping orange gashes oozed spores that spiraled down the harrowed bodies of the ancient giants. Mycelial wedges squirmed into their tight layers of protective underbark and water-feeding cambium. The blight slowly choked American chestnuts to death, toppling entire forests throughout the temperate Appalachian and Allegheny ranges.

Though their fine straight planks continued to stand vigil in the fence lines and barns of family farms, the trees themselves seemed to suddenly disappear.

“I can remember well that all of them were gone by 1927 on the Wells Creek farms in Eastern Kentucky where I was born,” Davis said.

There is no mention of this massacre in the New York Times’ glowing profile of Parsons’ 30-year tenure over the city’s Department of Parks. But his legacy came at a cost which Appalachia has paid ever since: The imported chestnut blight killed nearly 4 billion American chestnut trees across 200 million acres of US forest. In less than 40 years it would obliterate enough ecosystems to drive some species into extinction. That fate seemed likely for the chestnut as well.

But a curious thing was discovered about the old forests in the mountains. The blight did not always kill the entire tree. Rot and death would spread through their venerable trunks and crumple their limbs — but their roots and stumps, cradled by the continent’s most ancient mountains, lived on in the sandy, acidic Appalachian soil.

Stumps generally survived the blight, and kept producing hopeful shoots for years to come. The diseased tendrils would stretch themselves toward the sun each spring, even while weaker and thinner than they ought to be, climbing skyward for five years or so before succumbing to the blight and dying back down. Most never even grew old enough to flower, but the trees kept trying. They still are: About 430 million American chestnut trees exist across the species’ native range today. In a sense, they were buying time for us to figure out how to save them.

Most surviving chestnut trees have a relatively tiny diameter at breast height, or DBH, measured at about 4.5 feet from the ground. As of 2022, roughly 84% of such trees were measured at one-inch DBH or smaller, while those whose DBH is 10 inches or larger only total in the tens of thousands. The only reason that estimate is known, or even possible, is because the chestnut has had other allies besides the mountains. The people of the mountains likewise refused to give up. And now, against all odds, the trees and their friends are winning.

Shepherds of the forest

The American Chestnut Foundation (TACF) is the Appalachia-based nonprofit that has given the disappearing tree its greatest hope for resurrection. TACF’s small band of tree stewards have fought for the species’ conservation since 1983, but they’re just the face of the volunteer-led local groups that power TACF every day. Citizen scientists are the eyes, ears and pruning shears of TACF. The group connects these local researchers to national experts and scientists at the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Forest Service. Thanks to those local communities’ efforts, TACF logged more than 500 of the larger chestnuts by 2022, and now tracks hundreds of orchards across the entire native range.

Jared Westbrook is TACF’s national science director, overseeing the testing and cultivation of orchard strains across every state chapter. Under Westbrook, TACF is taking a few different approaches to preservation, each offering a different degree of success depending on the region. The key strategy, however, is to backcross-breed blight-immune Chinese chestnuts (Castanea mollissima) with the heirloom American chestnuts in order to create a hybrid species that is as genetically as close as possible to the native species while still offering the maximum possible disease resistance.

“We retain a very small fraction — 1% or less — of the trees that we plant,” Westbrook said. “And so now we've gotten to the point where we've been able to generate populations that inherited most of their genome from American chestnut. They have some intermediate resistance. We've identified that needle in the haystack.”

Much as animal species can be bred for hardiness by selectively mating the strongest pairs, the scientists gather the handful of chestnut trees from each stand that show improved blight resistance over their predecessors, and use only those for cross-breeding. To resurrect a sprawl of ancient woodlands is no task for the short-sighted, nor one that can be measured in units as tiny as years. Westbrook and TACF have learned to think in generations.

“We have good parents and cross them together,” Westbrook said. “And we generate the kids and we select even better. We have to do that repeatedly with more generations until we have trees that have adequate resistance where they can reproduce on their own in the forest.”

This hybrid breeding approach is slow work that requires methodical care from thousands of volunteers — planting hundreds of thousands of trees, physically maintaining and testing each of them, and cutting back all but the strongest. But it’s working. Results over the last decade, Westbrook said, have exponentially surpassed those from TACF’s entire 40-year history.

“We've improved the blight resistance like five times over from what an American chestnut has had naturally, looking at our forest trials. And yet, these victories are still not as resistant as Chinese trees,” he said.

Asked if he could roughly gauge the overall increase and how far the trees had to go, Westbrook said that “on a scale of zero to 100, the average resistance we're getting right now with our best parents is about 40 or 50.”

The ethics of tree medicine

TACF’s hybridization strategy isn’t the only approach to saving the American chestnut, however. Other groups aim to preserve the historical genetic diversity of the native species. Rather than lose the unique and native American tree and replace it with a newly created hybrid, they hope to cure the native species before it disappears.

The chestnut blight secretes a searing chemical, oxalic acid, into the tree bark, eventually causing cankers and death. In what are called Darling chestnuts, however, a CRISPR-modified wheat gene is inserted into the tree and thwarts this acid with minimal genetic alteration. Basically, this allows the creation of 100% pure American chestnut trees — or at least very close to that — with just one gene added.

Westbrook said that while TACF is working with other groups to refine this potential solution and preserve the heirloom American chestnut varietal, there are still significant hurdles to clear. Long-term resistance of trees with the inserted gene is unclear, and the gene creates an array of unpredictable side effects.

“The trees don't grow as tall for example,” he said. “They don't survive as well. They're a little more sensitive to stress....It’s like having a fever all the time, like your immune system is overactive. And you can't turn it off. So you have the advantage of, I guess, genetic purity, but the side effects of an overactive approach may not be a viable strategy going forward.”

TACF is now exploring ways to make sure that the wheat gene only “turns on” when the tree is fighting off the blight, and only in the right tissues.

“That’s the more pinpointed, precise way of making the tree resistant rather than it being on volume 10 all the time,” Westbrook said.

Chinese hybrids, however, already offer an entire immune system naturally geared for this challenge. For example, chemicals in the Chinese trees’ bark counter the acid cankers by creating a sort of scab around the injury.

“It’s all about this intelligent immune system in a tree that recognizes it’s under attack,” Westbrook said. “It enables them to mount an appropriate defense where it is only on when it's needed — and only as much as necessary, only as little as possible.”

Kitchen table conservation

In Kentucky, the slow process of careful hybrid cultivation means TACF volunteers like Ken Darnell can find themselves taking 3,700 steps forward and about 3,660 back.

Darnell is what one might call a kitchen-table conservationist. Before joining TACF, he spent his career leveraging forestry science and biotech for kitchen cabinet manufacturing. Now he says he’s ready to get back to the forest. One hike after another, handling one tree at a time, he is full-time TACF volunteer and the head of its Kentucky chapter, spending nearly 40 hours a week managing the orchards and organizing efforts across the state.

In just one orchard, Darnell oversaw the planting and maintenance of about 3,700 hybrid chestnuts in the last eight years. By the end of this year, all but the 40 strongest will be cut down. Those 40 or so trees, which prove maximum resistance against blight, will be used to hand-pollinate other orchards, making the next crop stronger. This orchard is a project in partnership with Eastern Kentucky University, the most highly maintained crop in the state. Its hybrids are about 15/16ths American chestnut and 1/16th Chinese chestnut.

“To plant those 3,700 trees was a lot of work,” Darnell said. “Kids, volunteers, members, Kentucky TACF chapter people, national leaders coming to help us — [it was] a tremendous amount of work and planning. Then once we planted those trees it was a lot of work to nurse them and baby them, to get them to grow up.”

That work includes weed control, planting, loading and fertilization. The Kentucky volunteers also have to watch over the trees throughout the year to protect them from the destructive ambrosia beetles, whose larvae would quickly kill half of the orchard if left unchecked. Volunteers must tend to each of the 3,700 trees, making the trek across the state three times per spring and spraying every single tree with protectants to give their tiniest leaves a chance at reaching maturity.

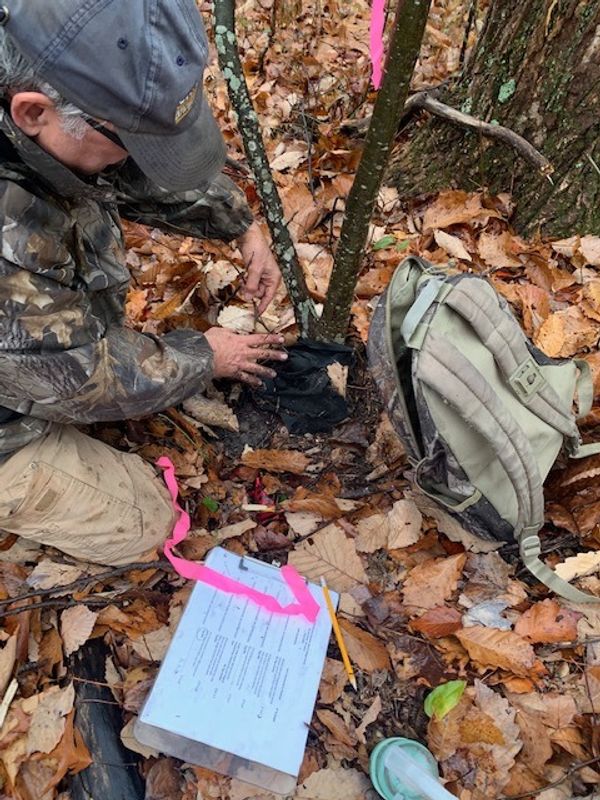

“Then we injected them with the blight. And what a mean thing to do to your baby trees,” Darnell said. “To test them, we actually acquired some blight in Petri dishes, cut a little hole in the trees, injected a piece of the blight from the Petri dish into the tree, and put a piece of tape around the blight in the tree, just to force the issue with the tree. Some of the trees inherit the right combinations of genes, some don’t.”

After giving the trees a couple of years to process the blight, the results become more apparent. The volunteers continuously sift the orchard, cutting off decaying pieces, sorting blight-stricken trees from those injured by other factors, measuring and recording each sproutling’s growth. Every two years or so, TACF scientists like Westbrook will come to the orchard to test the trees and guide the orchard selection.

“It helps us speed up the process and choose more quickly which trees to cut. It sounds like a sin to cut more trees, but it’s to let the better trees grow more vigorously,” Westbrook said. “That will let us get down to the final 40 or so that will have enough blight resistance to use their nuts for controlled cross-pollination.

“When we have these 40 trees, we can do any combination of breeding with them just once. We'll try to have 40 trees from diverse parents across the orchard. We don't want 40 trees of a single mother — that's not a good idea. We're trying to have genetic diversity.”

In Appalachia, the chestnut was once known as the “cradle to grave tree.” Its straight-grain, lightweight planks were used for both cradles and caskets. Its early summer blooms ensured plentiful offspring and protected it from an annual spring-frost death visited on other nut trees. Its thick foliage drew in game for hunting, sheltering small ecosystems and wrapping communities in a dense protective layer against the cutting mountain winds.

Kentuckians haven’t forgotten this. And Darnell now stewards the chestnut stands from cradle to grave, preserving their legacy and arborcraft, one sapling at a time. He watches as volunteers bring their kids into orchards to help maintain the tree communities, shows them how to care for the trees as the trees once cared for the people.

He often hikes the orchards in shared delight with others, and he says he’s not giving up on the trees any time soon. He can already walk through the shade and light of the newer 20-year orchards, enjoying the early fruits of TACF’s work, and giving us all a glimpse of the chestnut’s future.

Side quest: The tongues of nut-worshiping women

There are many names the world over for what we call the American chestnut tree, including the names given it by the first peoples of its native range. In Choctaw, it is otapi. Among the Powhatan-speaking Algonquian tribes of Virginia, the trees are opomens. The Iriquoian language of the Cherokee or Tsalagi peoples has several words for them, including tili (ᏘᎵ) and unagina (ᎤᎾᎩᎾ).

As far as Eurocentric science is concerned, however, our American chestnut’s official name is Castanea dentata. The Latinized Castanea is a more definitive version of the Greek kastana — an ancient linguistic mutation of the Tsakonian kastanakon karuon (κάρυον) meaning “nut,” “hard-shelled seed” or “kernel.” For Greek writers, it referred to chestnuts, walnuts, hazelnuts and other nut-bearing trees. The trees, they say, were danced to life.

The Peloponnese area of Greece, called Tsakonia, was once called Kynouria and became known for the hypnotic, serpentine dances of the dryads called Karyatides. That word means “ladies of the nut tree,” and the nymphs were devotees of the goddess Karya, chthonic all-mother Kar in Crete’s oldest pre-Minoan stories. She likely originated in the Babylonian kharimati, singing priestesses of bull-riding goddess Ishtar. Karya was later beloved of Dionysus, and was finally changed into a nut tree.

The city where the women danced became Karyai. Under the Greeks, the priestesses adopted Artemis Caryatis, moon goddess of the wilderness, twin sister to Apollo, the sun god. In 12-day autumn festivals they wove hands together and circled chestnut, walnut and hazelnut trees, their dance through labyrinthine groves like Ariadne’s gift to Theseus.

To this day, a magnificent plane tree crop still surrounds Artemis’ temple at Karyes. It’s said they were planted by King Menelaus in 1100 B.C., a tribute to his tree-cult devotee wife Helen of Troy, sister of the Castores (the mythic Gemini). And to this day in Kastanitsa the annual Chestnut Festival is held at the end of October.

The Greek Karuon or kỹros (κῦρος) both come from the Old Persian Kūruš (“like the Sun”) and meant not just a chestnut shell but a brain shell, a skull (as in cranium or crane). Here’s the connection: It becomes “horn” when written kérat (κέρᾰ, root of keratin), and as voú-keras (βούκερον) it becomes “ox or bull horn.” Finally, as kerátona vomón (Κεράτωνα βωμόν) it is the “Horned Altar” around which Theseus first danced in praise of the sun-god Apollo. A dance called the Crane.

If you steer your boat west from the Greek isles, you will find the largest and oldest known chestnut tree in the world. It has been living on Sicily’s Mount Etna for nearly 4,000 years. With an awe-striking circumference of 190 feet, it is called Castagnu dî Centu Cavaddi (the “Hundred Horse Chestnut”), which some argue is the largest single tree in the world. Its name is a boast of size, recalling a huntress queen once caught in a thunderstorm, who sheltered inside the tree with her entire retinue and horses. The first government act of environmental protection in the world is thought by some to have come from Sicily in 1745, when it instituted protection of the Hundred Horse Chestnut.

The same blight that killed one out of every four hardwood trees in Appalachia took hold of Greece in 1963. Just as in Kentucky, the devastation ripped an important cash crop away from rural mountain communities, spurring on city-bound migration as people fled withering agrarian economies. And just as on the eastern seaboard of North America, the damage spread faster in a vacuum of ecological protection.

By 1988, the threat wormed into Mt. Athos’ coppice forests, a UNESCO-protected site where local politics finally forced action. Losses were slowed in 1998 with a new conservation project that clear-cut infected trees, then deployed a naturally occurring virus against the fungus. Another project built on its success had spread across 29 counties by 2016. The virus spread and the orchards began to recover.

But Greece produced 18,000 tons of chestnuts a year in the 1960s, and by 2005 that was down to 11,000 tons. In Karystos, on the Greek island of Evia, a reforestation project now seeks to restore a magical chestnut forest called Kastanlogos, the oldest in the country. The project expects to restore 30,000 chestnut trees by the end of this year.

If the bias of Western empirical science leads us to ignore the names given to American chestnut trees by those who knew them first, then consider that the oh-so-scientific term of Castanea dentata asserts that the tree is a magical being. And it’s a she. To be exact, she’s an ancient pre-Hellenic goddess who was transformed into the tree. And her name isn’t Castanea; it’s Karya.

Her people have not given up on navigating her pervasive ecological disease. And her Greek dryads, the Karyatides, still dance today.

Biodiversity and cultural-climate change

As much in Kentucky as in Greece, the people of a place are fated by its forests. We may not have an ancient Minoan dance to celebrate the chestnut tree, but we’ve got a song from Dolly Parton, whose uncle Bill Owens was a 25-year TACF member and oversaw the planting of hundreds of American chestnuts at Dollywood. No Appalachian could ask for more goddess lore than that.

Preserving the diversity of Appalachia’s forests has also meant preserving the diversity of its people and culture. In the southern mountains of Kentucky’s Cumberland County lies a place once called Coe Ridge or Zeketown. It was founded in 1866 by Ezekiel and Patsy Ann Coe, a formerly enslaved couple who purchased the land after reclaiming their enslaved children, creating a prosperous Black community that would thrive for nearly a century with the help of 300 to 400 acres fueling its chestnut and timber trade.

Once the chestnut trees disappeared, though, Coe Ridge began to fade. Outward migration sent residents looking for work in neighboring Illinois, Ohio and Virginia. As historian Donald Davis writes, the chestnut played such an important role in the diet and economy of Appalachia that its loss helped tilt the region’s marginalized populations away from “a semi-agrarian and intimately forest-dependent way of life” to one concentrated in more industrialized areas.

That industrialization would come at a steep cost to mountains, forests and people. Coal mining, natural gas fracking and the accompanying pollution of air and water from unchecked resource extraction all ripped through the natural wealth of forests, leaving behind impoverished communities, multiple health hazards, few and distant hospitals and countless small towns with mortgaged futures.

Cassie Stark, TACF’s mid-Atlantic science coordinator, says her region is seeing specific challenges from climate change on top of the chestnut blight they’re already facing. The main threat is a root rot in the trees caused by a soil-borne pathogen called Phytophthora, a new strain of the same microorganism that helped cause the Irish famine of the 1840s.

“This used to be mainly a problem in the southern region. Now we're seeing it more northern,” Stark explained. “Phytophthora thrives on these humid, moist, kind of swampier sites. Unfortunately, that is the kind of problem that's kind of creeping up into our region as things start to warm up.”

An ecology of hope

If you scoured a map of the U.S. for the precise spot where climate change destruction and the country’s mental health epidemic most visibly intersect, your finger would likely land on Appalachia.

The growing pile of studies on mental health disparities in the region has been an early warning for other landscapes as climate-change dread creeps into America’s psychic periphery. In 2017, a study on Appalachian women who lived near gas extraction wells reported greater feelings of powerlessness and increased community illness to the industry’s presence. In 2012, those living near mountain-top removal sites were found to have a higher risk of mental health problems.

Also in 2012, a different study from the Appalachian Regional Commission found that “persons in Central Appalachia, where coal mining is heaviest, are at greater risk for major depression and severe psychological distress compared with other areas of Appalachia or the nation.”

That distress can be heard clearly enough in the voices of Appalachian students recorded in one 2022 study.

“It's really frustrating because the more I learn about stuff, the more overwhelming it becomes,” said one student. “I want to do my best to make a difference. I use my reusable bags and I have my metal straw. I do so much on the small scale in my everyday life to make myself feel like I'm making a difference, but it's frustrating knowing that the cause of all of this is out of my hands and there's nothing I as an individual can do to make as big a difference as I want to.”

Other students felt worn down, between concern over impending climate catastrophe and family political tensions. The region is often described as one where community identities are rooted in a sense of “place,” a bone-deep sense of connectedness not just to the land, but the collective. In many regions and groups, climate change drives feelings of hopelessness and powerlessness, which can set off a “paralyzing downward spiral of despair.” But those feelings of are felt even more strongly by those with a keener sense of connectedness to their environment.

It’s a double-edged sword: That sense of place-connectedness, if actively cultivated with a community, may also render us more resilient against the psychological weight of climate change. It’s no surprise that TACF’s efforts to conserve Appalachia’s biological heritage have had a fortifying affect on the spirits of its volunteers and members. Stark says she can see this effect in real time.

“We're often flooded with the news as to what's going on and how are we going to fix it. And ‘how do I do my part?’ and ‘Is one person enough?’ and ‘What can I do?’” Stark said. She gets a lot of calls and emails from people who “just happened upon our website, and they’re like, ‘How do I get involved? Where can I volunteer near me?’ They want to come out, they want to see the trees and they want to physically start making that difference and doing what they can.”

Increased volunteering and the recent breakthroughs in genetics are actually changing the pace of TACF’s work, hinting at a newfound momentum fueled by this symbiosis.

“I joined at an exciting time,” Stark said. “The progress we’re making in the past five years, compared to the progress that we've made in the past 30 years, is really astounding. That's just because of new technology and the way science is progressing. So I just feel really hopeful.”

We know from dozens of studies that time spent in the forests affords nearly immediate benefits to mental health, offering promising results for those with dementia, substance use disorders, depression and anxiety. There’s an umbrella term for these kinds of therapeutic interventions involving nature and animal conservation: “green care.” A 2023 systemic review of several meta-analyses likewise found that psychological and physical connections with nature improve both human well-being and the actual product of nature conservation work. It’s a symbiotic joy: The more helpful you are to the trees, the better your mental health.

Interestingly, these studies show we feel even better when we believe we’re in a more biodiverse forest and are contributing to its biodiversity. Another 2023 study surveyed 500 people who performed one 10-minute activity five times over eight days in any place with nature nearby and found specifically that “nature-based citizen science potentially supports people's well-being over-and-above the benefits of being outside.”

Last year, Oxford University psychiatry experts and National Health Service members called nature restoration work “an essential mental health intervention.” And actual forestry work itself — the light-intensity grunt work of planting, pruning, hauling saplings and tromping around a bit — was found to specifically improve participants’ sense that they themselves have been mentally and emotionally restored.

These restorative benefits seem to be growing among TACF volunteers, too. Members seem undaunted by the length of the intergenerational journey ahead, according to Stark. As volunteers work shoulder-to-shoulder with their neighbors, the long arc of the work ahead can help to soften the anxiety about impending doom, and to generate resolve, resilience and hope.

“The volunteers I work with are all so optimistic and passionate, and believe that this is something that we can accomplish. And a lot of them know this might not be in their own lifetime,” Stark said.

“It's a long process of restoration, especially when you're working with a tree. Their life cycles are so long. But just setting that groundwork for the next generation coming behind them, and continuing to work, is the idea.”

If you feel hopeless, if you are afraid and paralyzed, come to the woods and listen. If you are lost in the labyrinth of despair, watching the creeping dread-rot hollow you out — whether you’re circling the dark on the uptown 1 train or bleeding out willpower under fluorescent lights — follow Ariadne’s telephone wires through the web of straight-grain utility maypoles up the mountain. Hike the winding chestnut orchards of Kentucky, thrice-circle their groves in the spring and let your children learn their names.

If you can’t bloom, if you tire of climbing and wither without end — come sink your hands like roots into the sandy soil and let your oldest allies lend you strength to grow anew in enduring hope. Slowly by the seasons, one kernel at a time, you will feel your heartwood restored.

“We say restoration is a process,” Stark tells me, “not a product.”