Saudi Arabia recently sentenced Nourah bint Saeed al-Qahtani to 45 years in prison after she had expressed her views on social media. This comes just a couple of weeks after a Leeds University student, Salma al-Shehab, was sentenced to 34 years in prison for using Twitter to retweet views of activists who are critical of the country.

There had been a few small signs that Saudi Arabia had been offering its women a few more freedoms in the past few years, but recent harsh prison sentences against women have sparked increased debate about the country’s human rights abuses.

Despite these cases, the country’s de facto ruler, Mohammed bin Salman, was invited to Queen Elizabeth II’s funeral, although in the end a government minister attended in his place. The fiancee of murdered journalist Jamal Khashoggi, Hatice Cengiz, criticised the invitation and its implications that the UK, and the international community, were turning a blind eye to Saudi Arabia’s excesses. Khashoggi was murdered inside the country’s Istanbul consulate in 2018.

One factor that means that the west is less likely to criticise Saudi Arabia right now is the Ukraine war.

Read more: Saudi Arabia: why Boris Johnson not getting an instant deal is down to history

The Russian invasion has led to petrol price increases, disruptions in the suuply of natural gas as well as inflation and other issues, which have left the west struggling – with some mainland European states, including Germany, suddenly waking up to their extreme reliance on Russian gas.

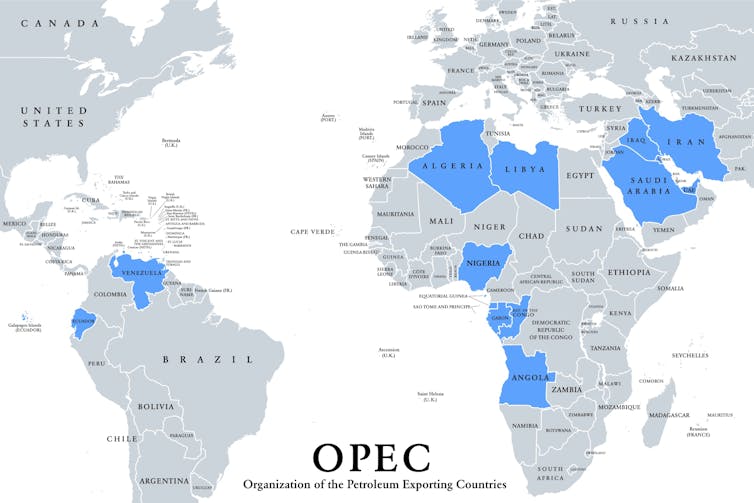

Even though the UK and the US are not as reliant on Russia as their mainland European allies, their national economies and populations have been also greatly affected because of globalised markets and economic interdependence. There is also a need to fill the energy gap left by Russian oil, and Saudi Arabia is one of the states that can help do this.

The UK and US governments have been trying to rebuild and secure Saudi Arabia’s continued support and partnership by carefully planned visits to maintain good relationships. Just a couple of weeks after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, former UK prime minister Boris Johnson visited Saudi Arabia to discuss oil and energy security.

While the US may be more energy independent than other western states, inflation and global recession as a result of the Russian war in Ukraine are still affecting its energy prices.

US president Joe Biden followed Johnson to Saudi Arabia in mid-July to pursue energy security talks, and to ultimately stabilise global markets. In an article written in the Washington Post, Biden pointed out Saudi Arabia’s strategic importance: “Its energy resources are vital for mitigating the impact on global supplies of Russia’s war in Ukraine”.

Biden has been more critical of the Saudi regime than his predecessor Donald Trump. As a result, Biden has not received a particularly warm welcome from the Saudis. But his determination to let Saudi Arabia be part of the solution to the global crisis gives Saudi Arabia increasing power.

Johnson’s visit to Saudi Arabia coincided with Saudi Arabia’s execution of 81 people. Yet, the prime minister’s office did not openly condemn the executions, only promised to raise the issue with the Saudis.

Saudi Arabia thinks that its relative importance has grown to such an extent that the west no longer dares to harshly criticise it.

Taking the long view

The imprisonment of these two women, however, is just an intensification of long-term oppression of women by the regime, while the west looks the other way.

The Trump administration avoided the issue, refraining from criticising Saudi Arabia’s human rights record. Trump made Saudi Arabia part of his first foreign trip and further affirmed the US longstanding policy of keeping a close partnership with Saudi Arabia. The Obama administration was more critical and raised some concerns over human rights, though it still maintained a stable working relationship with the Saudis.

The UK, as another key global actor, has more or less followed the same trajectory as the US. It cooperates with Saudi Arabia on a variety of matters – politically, military, economically, and even selling Saudi Arabia arms that the latter then has used to indiscriminately target civilians in Yemen.

Some would argue that the west has been letting Saudi Arabia get away with human rights violations for years.

Saudi Arabia has had one of the poorest human rights records in the world for decades. Year after year, organisations such as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International report Saudi Arabia’s human rights violations. Under Saudi Arabian law many basic human rights including freedom of speech and the right to a fair trial are limited or denied.

While some token advances have been made lately – such as women being allowed to drive – these are really just symbolic efforts to disguise the reality. Women remain second-class citizens. Saudi women still cannot get married or obtain healthcare without the permission of their male guardians, or pass on citizenship to their children. This guardianship of women has been in place for decades and world has tolerated it.

Even the most shocking cases of human rights abuses by the Saudi regime have often been met with very weak international responses. When Saudi Arabia executed 81 people without a fair trial in one week in mid-March the US barely condemned it. The United Nations did condemn the lack of fair trials and voiced concerned about the wide interpretation of “terrorism” under the law but took no further action.

The UK declared its commitment to the protection and promotion of human rights, as shown in its review of UK foreign policy, defence and security – where it proudly announced it was the first European state to impose sanctions on Belarus for its human rights violations.

The same document also stated that the UK would build upon its close security partnership with Saudi Arabia, while not mentioning any of that country’s human rights violations. Currently, there are no UK financial sanctions on Saudi Arabia , even though they are imposed on other regimes with arguably less terrible human rights records than Saudi Arabia.

Because of the Ukraine war, Saudi Arabia’s record of violating human rights is unlikely to improve and may even worsen in the near future. But the west needs a friendly regime in Riyadh for all the reasons already discussed – and these issues are not likely to go away any time soon.

Veronika Poniscjakova does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.