In How Hitler Hijacked World Sport (2011) — the story of one man co-opting sport for the Nazi cause — the author Christopher Hilton says, “he approached sport as he approached everything else, by being prepared to exploit it in the most shameless ways as long as it served his purpose. It brought an additional paradox because sport was built on exactly the opposite principles to those Hitler and the Nazis held…”

Less than a century later, another man and another political system is attempting the same strategy with a missionary zeal. Mohammed bin Salman Al Saud, the Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia, understands the power of sport to lend credibility to and buy acceptance for a regime which may not believe in human rights but has the resources to make the world act as if it does not matter. There are those who believe that all the perfumes of Arabia will not sweeten the country’s image, but they are increasingly in a minority.

The latest to join the Saudi bandwagon is tennis star Rafael Nadal, who has trotted out the usual excuses about spreading the game, attracting children to it, and so on. John McEnroe has called it a slippery slope for tennis across the globe.

Also, in March, Riyadh will host the top eight players in the world for the $1 million dollar inaugural Riyadh Season World Masters of Snooker. This time there is an innovation — a 23rd ball known as the Riyadh Season gold ball, and worth 20 points.

The questions of morality versus market, human rights versus convenience, and of ‘sportswashing’, or using sport to distract from a country’s societal abuses, aren’t new. Saudi Arabia simply have more funds. And as always, morality shares a room with hypocrisy in the house of politics.

Top athletes on playing contract with Saudi Arabia

Neymar (Al-Hilal-Saudi Pro League)

Cristiano Ronaldo (Al Nassr-Saudi Pro League)

Karim Benzema (Al-Ittihad-Saudi Pro League)

Jon Rahm (LIV Golf)

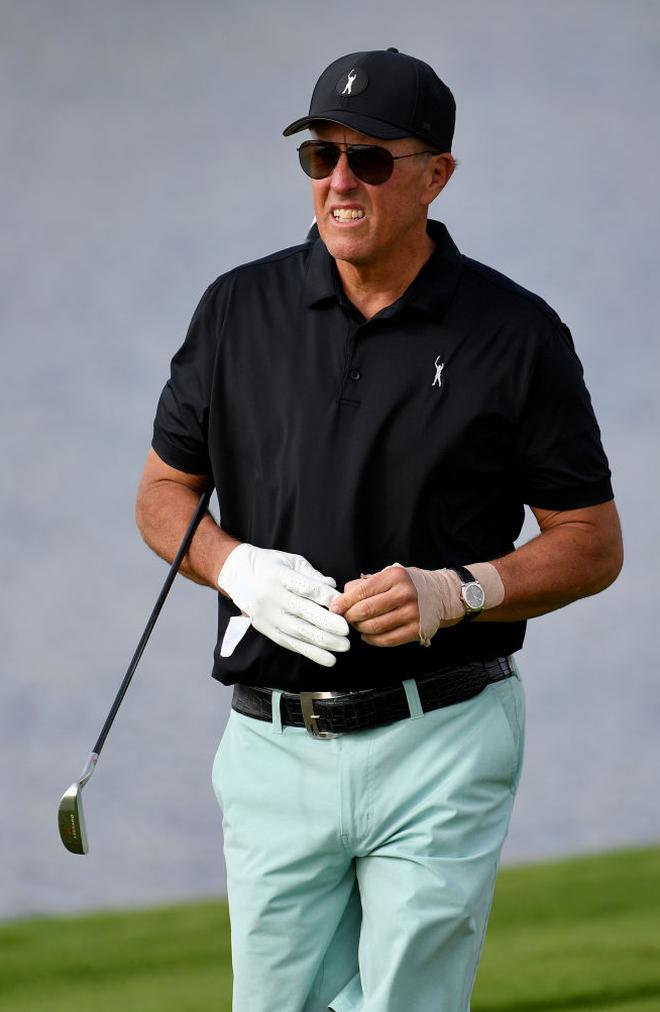

Phil Mickelson (LIV Golf)

PR case study

When Saudi Arabia unpacked the Vision 2030 programme nearly eight years ago, sport (alongside investment opportunities, tourism and entertainment) was merely one of the avenues towards a more palatable image for the country. Now, the desert kingdom could become the sports hub of the world. The re-branding is on an unprecedented scale, the PR exercise likely to become a case study in textbooks.

Some years after the Public Investment Fund (PIF) — worth $700 billion — was revamped to diversify the country’s oil-dependent economy came the murder and dismemberment of dissident and journalist Jamal Khashoggi. Then came the alleged mass killing of Ethiopian migrants and more atrocities that seemed to confirm the perception of Saudi Arabia as a backward, repressive country with regressive laws.

Only a small part of the PIF is invested in sport — a much greater amount is invested in U.S. venture capital funds — but sport is sexy and guaranteed to give a bigger bang for the buck. It works both domestically and internationally. Sixty-three per cent of the population is under the age of 30, and the unspoken social contract between the rulers and the youth is this: we will get you everything from international stars to futuristic cities, tourists and more. In return, keep your mouth shut.

Reputation-laundering through sports is important, but the greater ambition is to change the global narrative about the kingdom. If it upsets the equilibrium of international sports, and leads into uncharted territories, that’s collateral damage.

When the PIF began to throw money at sportsmen and administrators, few ducked. Most welcomed it, especially footballers like Cristiano Ronaldo who were close to the end of their careers anyway. Saudi Arabia might not have known it would be so easy.

The kingdom hosts a range of sports events, from Formula One to WWE, the world’s richest horse race, heavyweight boxing. In 2021, the PIF financed the purchase of Newcastle United football club in the English Premier League, then spent $2 billion on its own LIV Golf which then merged with the official Professional Golf Association in June 2023. In 2034, Saudi Arabia will host the football World Cup. A decade is a long time in sport.

There has been talk of investing in the Indian Premier League too. And there is a $38 billion plan to become an esports hub by 2030. There have been offers to buy Formula One, and controlling stakes in the U.S. leagues NBA and NFL, and the ATP (tennis). All this has the fascination of watching a predator swallowing its prey.

World’s richest sporting leagues

National Football League (U.S.)

Indian Premier League

English Premier League

Major League Baseball (US, Canada)

National Basketball Association (US, Canada)

“We know they killed Khashoggi and have a horrible record on human rights,” the golfer Phil Mickelson said while joining the LIV tour. “They execute people over there for being gay. Knowing all of this, why would I even consider it? Because this is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity...”

Sports for humanity

Athletes will be judged by the choices they make; what might be great for the individual is not always good for the sport. “What I know about morality and the obligations of men, I owe to sport,” said Albert Camus. Morality and sport ought to go together. Sport is an artificial construct, but what it stands for isn’t artificial: inclusivity, fairness, justice, diversity, empathy. Sport is what makes us human, a bubble where we can see our better selves. To use it to support policies that make us less than human is a cruel paradox.

Like the American Mickelson, Saudi Arabia too see it as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. Mickelson’s country doesn’t see the contradiction in cozying up to the Crown Prince after their President Biden had called Saudi Arabia a ‘pariah’ following Khashoggi’s murder. The U.S. is Saudi Arabia’s second largest trading partner, with $46.6 billion in trade in 2022. Last year, the U.K. did $21.7 billion worth of trade with Saudi Arabia. When sports stars ask why individuals should be expected to make decisions their countries shy away from, there is no clear answer.

“Mohammed bin Salman’s rule has been a truly dark time for human rights in Saudi Arabia, and no amount of talk about economic visions or of an expansion into new sporting ventures should be allowed to distract from that fact,” says Amnesty International. Sportswashing, however, cannot succeed without the co-operation of individuals and countries which place profit over probity.

“We are reforming,” said Saudi Sports Minister Abdulaziz bin Turki Al Saud in an interview to the BBC, “such events help us to reform.” The Minister’s admission that reforms are necessary might be significant. The enthusiasm with which administrators are genuflecting before the Saudi determination for a seat at the high table is changing the face of international sports.

Few can refuse the blandishments. Lionel Messi, who turned down an offer reportedly around half a billion dollars (he chose to play in the American league instead) is a tourism ambassador for $25 million. He is on social media saying things like, “I love Saudi Arabia. I didn’t realise it was so green”, posting photographs of his family holidaying there. Turns out his family was keener on the beaches of Miami than on the sands of the desert, hence his decision.

In 2018, Roger Federer had turned down a $2 million offer to play a single match in Jeddah. Tiger Woods turned down $750 million when the LIV Golf Series was inaugurated.

Already the PIF spends more money than the GDP of countries like Barbados on sport. Saudi Arabia have no hope of recovering any of that in the near future. But financial profit isn’t the motive.

“In 1940 the Olympic Games will take place in Tokyo. But thereafter they will take place in Germany for all time to come…” This is Hitler, quoted by his architect and armaments minister, Albert Speer. The idea was to have a stadium in Berlin holding 450,000 people for the quadrennial event. Hitler was planning to hijack the Olympic Games. And we’ll leave it at that.

The writer’s latest book is ‘Why Don’t You Write Something I Might Read?’.