Russian assets frozen as punishment for Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine could be used to rebuild the war-torn country, in a scheme proposed by the European Commission that seeks to answer the long-running question of what western allies should do with the hundreds of billions of pounds trapped by sanctions on the Kremlin and its associates.

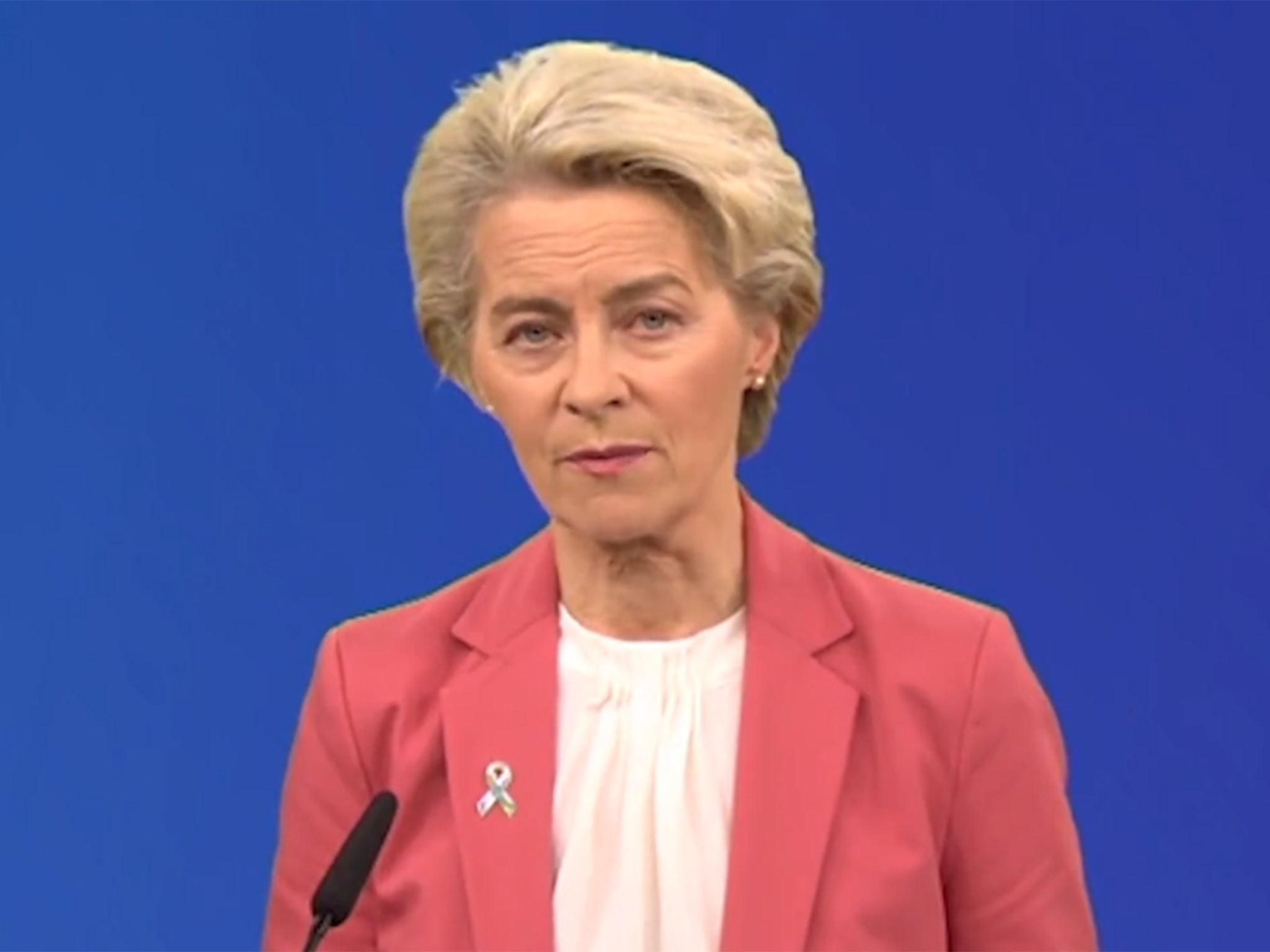

Ursula von der Leyen, Commission head, said Ukraine’s allies should seize the more than €300bn (£259bn) of Russian money held up by sanctions and invest it, putting the returns towards Kyiv’s estimated €600bn restoration bill.

In a statement on Russia’s accountability for the devastation wrought by the invasion, Ms von dr Leyen also said the EU was pushing to set up a specialised court “to investigate and prosecute Russia’s crime of aggression”.

The 27 EU member states along with the US, Britain, Canada and others have frozen billions of euros worth of Russian oligarch assets, with around €300bn of the Russian central bank’s foreign reserves locked abroad.

Ms von der Leyen said: “In the short term, we could create, with our partners, a structure to manage these funds and invest them. We would then use the proceeds for Ukraine.

“And once the sanctions are lifted, these funds should be used so that Russia pays full compensation for the damages caused to Ukraine.”

She added that the EU was working with international partners to develop such a scheme.

Officials in the EU, US and other allied countries have been at pains to devise a way to legally seize frozen Russian assets.

The problem for the EU, according to Reuters, is that in most member states seizing frozen assets is only legally possible where there is a criminal conviction. Also, many assets of blacklisted Russian citizen are held in the name of family members or front people, making them difficult to seize or even freeze.

Canada recently passed legislation allowing the government to order seizure of the assets of an individual deemed to risk a “grave breach of international security”.

Maria Nizzero, an analyst from the Royal United Services Institute, a British defence and security think tank, said this method has limited scope as such an order would be unlikely to stand up to challenges in the courts and could serve to dilute the impact of the wider sanctions regime.

In Britain, Ms Nizzero said, authorities are yet to decide the scope of their asset seizures, as politicans cannot agree on whether to take the opportunity to target Russian dirty money at the same time.

“A choice is needed, one that the UK is yet to make: while some MPs would like confiscation efforts to tackle the UK’s dirty money problem, others firmly believe they should be linked to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine,” Ms Nizzero said, adding that the “threat that dirty money poses to national security” warranted its targeting.