Russian president Vladimir Putin has yet to call for universal conscription, although he recently announced mobilisation of 300,000 reservists. The reason why the Kremlin has not introduced a wider policy may lie in the history of conscription and its impact on public support for war.

In recent research, my colleague Doug Atkinson and I analysed a dataset of everyone serving in the US army during the second world war. Although there are a number of obvious differences between the US of the 1940s and present-day Russia, both countries used selective – rather than universal – conscription to staff their military.

The way the US conscripted its military was deliberately hard to understand. It also helped shield certain voters who were crucial to electoral success of the Democratic Party at the next election.

In December 1941, the US faced Germany and Japan with their massive modern military forces. It had to quickly convert its industrial output to a wartime footing, modernise its own military and conduct offensive operations on four continents. Victory would require a military staffed by millions of soldiers, engineers, technicians and administrators, backed up by the full agricultural, industrial and intellectual power of the civilian workforce.

Anticipating involvement in the second world war, the US Congress passed the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940, which created a way to rapidly conscript large numbers of soldiers. The Selective Service System (SSS) relied on the judgement of political appointees and local draft boards to choose who was conscripted. In spite of whatever good intentions may have been behind it, the conscription of young men for military service was unequal. Nearly 140,000 fewer soldiers enlisted in the military from “swing” counties than “safe” counties (either backing or opposing the government) – a force equivalent to the Allied landing force at Normandy in June 1944.

Support for government and war is likely to dwindle among families who experience loss or injury. Governments may lose the support of not only those families but also their friends, neighbours and coworkers.

Our research suggests that strong core supporters and opponents of war are unlikely to shift their support, even in the face of losses. So the government doesn’t gain much from protecting those voters from enlistment. Therefore, the group most likely to benefit from selective conscription will be weak or “tenuous” supporters – swing voters – many of whom are likely to “bolt” back to their previous party. Keeping their dissatisfaction low is vital to remaining in power.

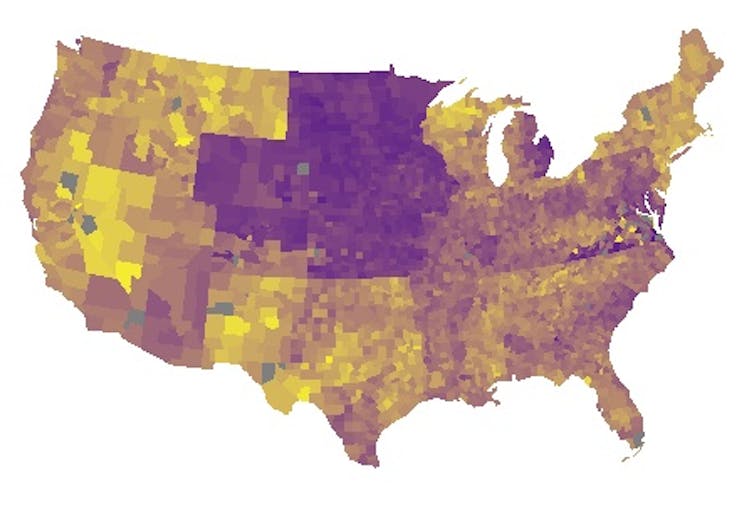

We drew on a new dataset of 9.2 million individual service records from the army, aggregated by county and year. The map below shows enlistment rates by county in 1942; brighter yellow refers to higher enlistment rates, while deeper purple reflects lower enlistment rates. There is clear evidence of lower enlistment in the swing Midwestern states and counties, with higher enlistment in the south and the northeast (the Democratic and Republican party base regions at the time, respectively).

Enlistments in the US army by county, 1942

Our findings show that in counties that narrowly supported President Franklin D. Roosevelt in previous elections, between 50-55% had fewer residents enlist into the army, volunteers and conscripts alike. Across a large range of models, we demonstrate how swing counties had fewer enlistments, either as a share of the total population or the military-eligible population.

This research shows that the easiest and most transparent way would be to bar swing voters from enlisting, but doing so makes it clear to the wider public that the conscription system was unfair.

The SSS created an inefficient, decentralised system of recruiting individuals, with two mechanisms that let partisans manipulate enlistment. First, the centralised leadership of the SSS – who reported directly to the White House – in Washington DC would set quotas for each draft board. The SSS and Congressional regulators then had the responsibility for ensuring quotas were met. Considerable discretion was given to the head of the SSS: its leader, Brigadier General Lewis Hershey, even instructed his subordinates:

“I do advise you to not leave a lot of memoirs on what you did. If you make decisions, you will not have time to justify them.”

Second, the SSS made counties the unit of organisation for draft boards, and allowed local civic leaders to participate in meeting enlistment quotas. These civic leaders were often local party officials as well. If a county did not meet its quota, then it would be up to the central SSS – again, who reported directly to the White House – to enforce the quota.

These twin mechanisms provide a ripe ground for partisan manipulation: a lack of transparency, often made by elected or appointed partisan officials, meant that the Democratic Party may have protected some young men in key swing constituencies from enlisting.

Parallels with Russia

Similarly, the Russian conscription system today is not easy to understand – regional governors are assigned quotas, and the central government has the discretionary power to punish governors who do not meet them. There are indications that Putin may be following the same strategy as the US to protect his support for the war, allowing him to stop politically valuable segments of society from being sent to the front lines.

“One idea was that the local governor was keen to meet his quotas like a schoolboy before schoolteacher Putin,” Alexandra Garmazhapova, leader of an activist group that has reported on the draft in the region told The Guardian.

We see evidence of this everywhere. Russian mobilisation in regions such as Dagestan, Buryatia and Siberia (historically anti-Moscow and anti-Putin) is rife with large-scale conscription, protests and violence. By contrast, unconfirmed reports suggest that Moscow and St Petersburg, areas which are more pro-war, have seen relatively low-profile conscription efforts.

Different approaches by Ukraine (where there is a nationwide conscription policy of men between 18 and 60) and Putin may in the long run lead to a more unstable Ukrainian government and a more stable Russian government. By protecting its winning coalition, the Putin regime is trying to ensure that anti-government action is small and manageable.

The Zelensky government in Kyiv probably must ensure victory if it maintains universal conscription. Battlefield failures, economic deprivation and long-term fatigue for the war might lead to its electoral coalition fragmenting and public support dwindling.

However, Putin may not be able to continue with his partial mobilisation strategy if his forces continue to take severe losses. His decision then will be whether he can risk undermining support for the war any further.

Kevin Fahey does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.