Russia is planning to buy “millions” of Soviet-era weapons from North Korea, a recent US intelligence report revealed. Britain’s defence intelligence has also confirmed that Russia is already using Iranian-made drones in Ukraine.

The revelations follow a series of diplomatic exchanges between Russian president Vladimir Putin and North Korean leader Kim Jong-Un to celebrate North Korea’s Liberation Day on August 15. The two leaders proposed a new strategic and tactical cooperation, and stressed the tradition of friendship between them, part of a recent Putin offensive to create and strengthen alliances with key authoritarian states.

In just a few days Putin has met China’s president Xi Jinping and Iran’s president Ebrahim Raisi, as well as promising a major trade delegation to Iran. Putin also promised to do everything he could to make Iran a full member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, a political and security alliance that includes Russia, China, Uzbekistan and Pakistan.

As Russia becomes isolated from the west following its invasion of Ukraine, the Kremlin is becoming more ideologically extreme, and is seeking to improve its cooperation with rogue regimes, particularly North Korea and Iran. This alliance, which is likely to include China, could pose a real threat to the west in the coming years.

Moscow enjoyed a close diplomatic relationship with Pyongyang during the cold war, and the Soviet Union was one of North Korea’s most important economic partners. The relationship changed dramatically in 1991 when the Soviet Union collapsed. Russia, no longer a communist country, focused on forging a positive relationship with western democracies.

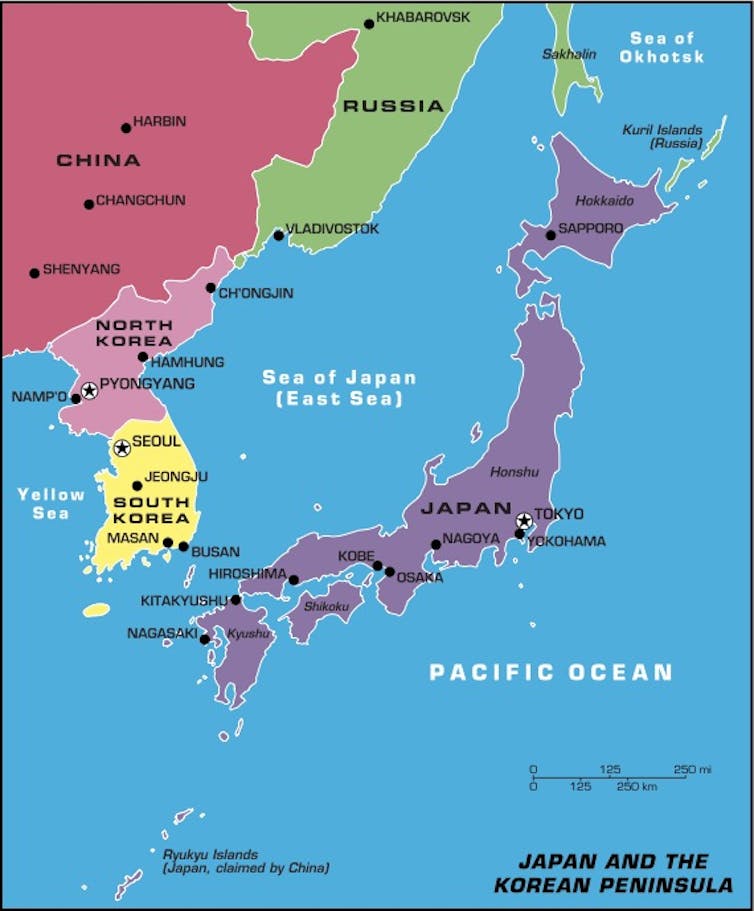

It prioritised economic relations over ideological ones, and sought to develop closer ties with the United States and South Korea. This damaged its relations with Pyongyang, and North Korea shifted its focus to developing a closer relationship with China.

North Korea’s isolation

When Putin came to power in 2000, he made attempts to renew Russia’s diplomatic relationship with North Korea. Kim Jong-Il, Kim Jong-Un’s father, even visited Russia on a few occasions.

However, the relationship was hindered by Russia’s deeply pragmatic approach to foreign policy. To maintain friendly relations with the west, Kremlin continued to condemn Pyongyang’s nuclear program.

This made it impossible for the two states to develop meaningful diplomatic relations. Russia’s economic and political isolation following its invasion of Ukraine provided a fresh opportunity for the two regimes to renew their ties.

Read more: Ukraine war: this map holds an important clue about Kremlin fears of Nato expansion

Since the fall of the Soviet Union, North Korea has become increasingly reliant on Beijing, with the vast majority of its trade and energy coming from China.

However, this relationship is not free from political tension. China’s key goal in the Korean Peninsula is to avoid the collapse of North Korea’s autocratic regime and prevent a reunification with South Korea.

This would be unacceptable to China, because it fears that a united Korea would bring greater US involvement in the region. As a result, China has been pressuring Pyongyang to become more moderate, hoping to stabilise the regime.

The strained relationship between Beijing and Pyongyang is one reason why Kim Jong-Un is likely to embrace the opportunity to get closer to Moscow and become more independent from Beijing. Another is that a closer relationship with Russia could result in subsidised energy and increased technological, scientific and commercial cooperation.

Some commentators argue that Russia’s turn to North Korea is a positive sign. They claim that Russia’s plea for weapons means that the military and economic sanctions against Kremlin are working. Unable to buy arms from other countries, Vladimir Putin is turning to North Korea and Iran, whose artillery is widely believed to be inaccurate and unreliable.

While this is true, a closer relationship between the world’s most dangerous autocracies should be a stark warning to the west. Russia’s interest in North Korea and Iran might be self-interested, it also signals that Moscow is no longer concerned with maintaining diplomatic relations with the west, and that it may be positioning the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation as a rival to Nato.

This autocratic bloc is almost certainly going to include China, whose relations with Russia deepened in the wake of the invasion of Ukraine. There is some evidence that Putin’s strategy is already working. In June, both Russia and China vetoed a UN resolution to impose new sanctions on North Korea as a result of its nuclear activities.

Read more: Ukraine war: Putin's failure will pave the way for China's rise to pre-eminence in Eurasia

This was an unprecedented move from two permanent members of the UN Security Council, who have condemned North Korea’s activities in the past. It signals a renewed effort to counter the global influence of the US and its allies who are, once more, seen as enemies rather than partners.

To counter a growing alliance of authoritarian regimes, the first step for the west is to acknowledge this is not necessarily a sign of Russian weakness, and not to rule out talks with the Kremlin.

While diplomatic engagement with these states might become increasingly difficult, engagement is preferable to a policy of isolationism, which risks encouraging more autocratic cooperation. The west must remain robust in its defence of democratic values and position itself as a necessary economic and strategic partner to autocratic regimes, or risk driving them further away.

Barbara Yoxon does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.