It’s official: the royals are returning down under. King Charles and Queen Camilla are scheduled to visit Australia and Samoa in October, attending events in Canberra and New South Wales (with more details to come).

Royal visits are designed to communicate a curated vision of imperial loyalty, but have always been a flashpoint for tension. In fact, the first royal visit to Australia was a disaster. It cost the lives of several people and exposed deep social divisions. The prince himself narrowly escaped assassination.

An Irish-Catholic history

In October 1867, Prince Alfred, the second son of Queen Victoria (and great-great-great uncle of King Charles) arrived in Australia for a grand six-month tour.

The highly anticipated visit coincided with the end of convict transportation. It was an opportunity for the colonies to project an international image as loyal and productive citizens of the empire, rather than distant penal outposts. Instead, it exposed deep tensions between Catholics and Protestants.

Today, we sometimes forget the cultural diversity of the non-Indigenous people of colonial Australia. In 19th century Australia, for instance, about 25% of these people were Irish – and most of these Irish were Catholic.

This was a problem for the authorities, who were trying to model Australia on British Protestant traditions. The original population of Ireland had already suffered centuries of violent marginalisation and had mounted several failed uprisings.

Even in Australia, the loyalties of the Catholic Irish were sometimes suspect and anti-Irish discrimination was common. Some job advertisements listed “no Irish” and negative racial stereotyping promoted the view that the Irish were stupid, superstitious and violent.

A ‘tremendous’ failure

The prince landed in South Australia in October 1867 before travelling to Victoria.

During the welcome ceremony in Melbourne, a Protestant hall displayed a provocative image of William of Orange which deeply offended the Irish Catholic community (the victory of the Protestant King William III against the deposed Catholic King James II at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690 ended any hopes of Catholic rule in Ireland).

A riot broke out and shots were fired into the Catholic crowd, injuring several people, including at least two children. William Cross, a 13-year-old boy, died of his injuries.

Things didn’t improve after that.

Three days later a free public picnic was expected to attract some 10,000 people. But 40,000 arrived – another riot erupting amid the rush for food and wine. At the last minute, the prince avoided the event for his own safety. Newspapers described the picnic as “one of the most tremendous and utter failures we have ever known.”

The chaos continued as the prince visited Bendigo, where fireworks accidentally set a model ship on fire. Three boys perished in the flames.

Two days later, a hall built especially to host a ball in the prince’s honour accidentally burnt to the ground on the night of his visit.

The assassination attempt

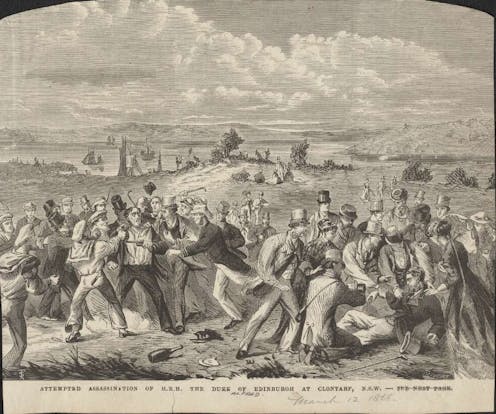

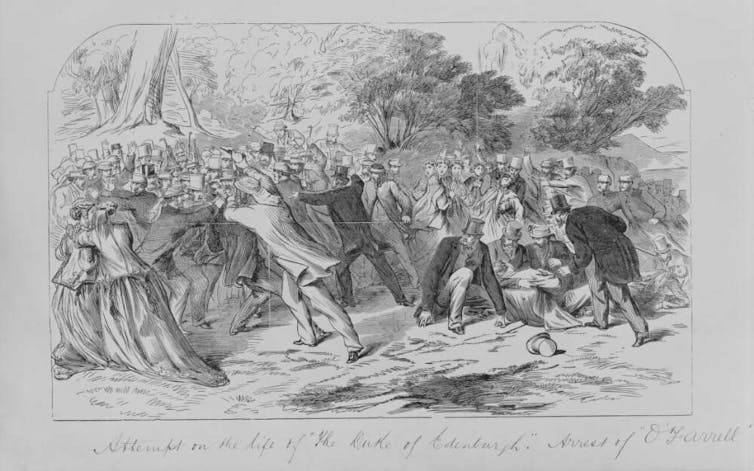

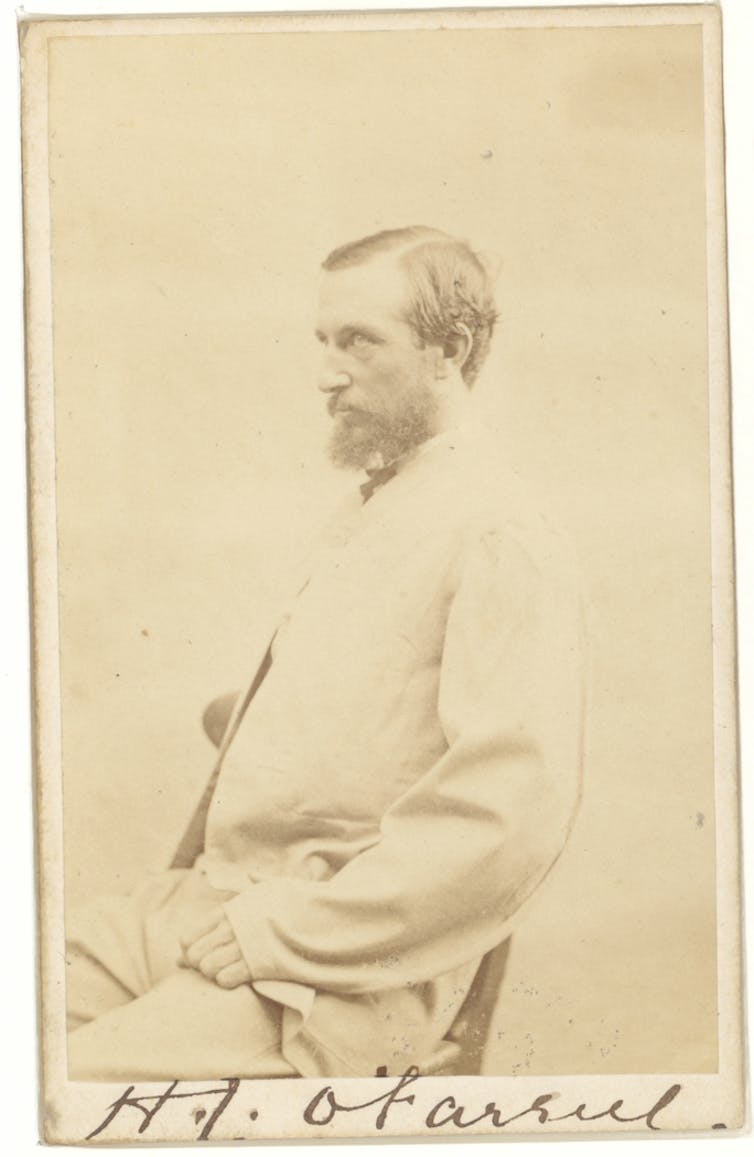

The prince then visited Tasmania and Brisbane before returning to Sydney. On March 12, 1868, while picnicking in Clontarf, an Irish man named Henry James O’Farrell approached the prince and shot him in the back. Miraculously, the bullet lodged in his ribs but missed his vital organs. The prince made a full recovery.

O’Farrell claimed to be part of a secret Irish Fenian plot. Fenians were members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, an organisation fighting for Irish independence.

Just two years prior, Fenians had attempted to capture Canada in return for Irish independence. They had also bombed a British prison only three months before the assassination attempt. Now, it seemed Fenians had infiltrated Australia.

The assassination attempt was a national embarrassment. Sir Henry Parkes, future premier of New South Wales, was certain O’Farrell represented the tip of the iceberg of a greater Irish conspiracy. The New South Wales government rushed through the Treason Felony Act to give authorities unprecedented power. It even made it a crime to refuse to drink to the queen’s health.

A national embarrassment

Meanwhile, the Australian public expressed extraordinary outrage. In the weeks after the assassination, more than 250 “indignation meetings” were held across Australia. The first meeting in Sydney, held the day after the assassination attempt, was attended by 20,000 people.

The media also played a central role; the recent invention of the telegraph meant the news travelled with exceptional speed while newspapers published racist cartoons reinforcing Irish stereotypes.

O’Farrell later admitted he had made up his claim of being a Fenian. And no evidence of a Fenian plot was ever discovered. At his trial, his barrister pleaded against the death penalty because of his “insanity”, a sentiment that was supported by the prince.

Despite this, he was executed. Today, historians accept O’Farrell was acting alone and that he suffered severe paranoia induced by mental illness and alcoholism.

Parkes was criticised for inciting anti-Irish hatred without evidence. Nonetheless, the event propelled his political career and he became NSW premier a few years later.

The Irish response

The Catholic Church denounced the assassination, while the Irish in Australia tried to distance themselves from any association with Fenianism.

Historians argue the assassination attempt resulted in the Irish-Australian community publicly reasserting their imperial loyalty. This community was at pains to emphasise a Catholic identity did not jeopardise their loyalty to their new home.

Ultimately, this led to greater cultural harmony and the emergence of a “nationalist” sentiment that would later power the movement to unite the colonies as one nation.

Today, a royal visit serves the same purpose it did in 1868. It’s a choreographed chance for the new king to show he cares about Australia – and therefore encourage loyalty among his subjects.

Ciara Smart does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.