Rising from playing Working Men’s Clubs in Yorkshire to US tours with Lynyrd Skynyrd and Ted Nugent, Be-Bop Deluxe were an arty enigma in mid-70s rock’n’roll. In 2019 band mastermind Bill Nelson sat down with Classic Rock to reflect on a life of musical adventures, flaming guitars and taking glam to shocked “hard, butch miners.”

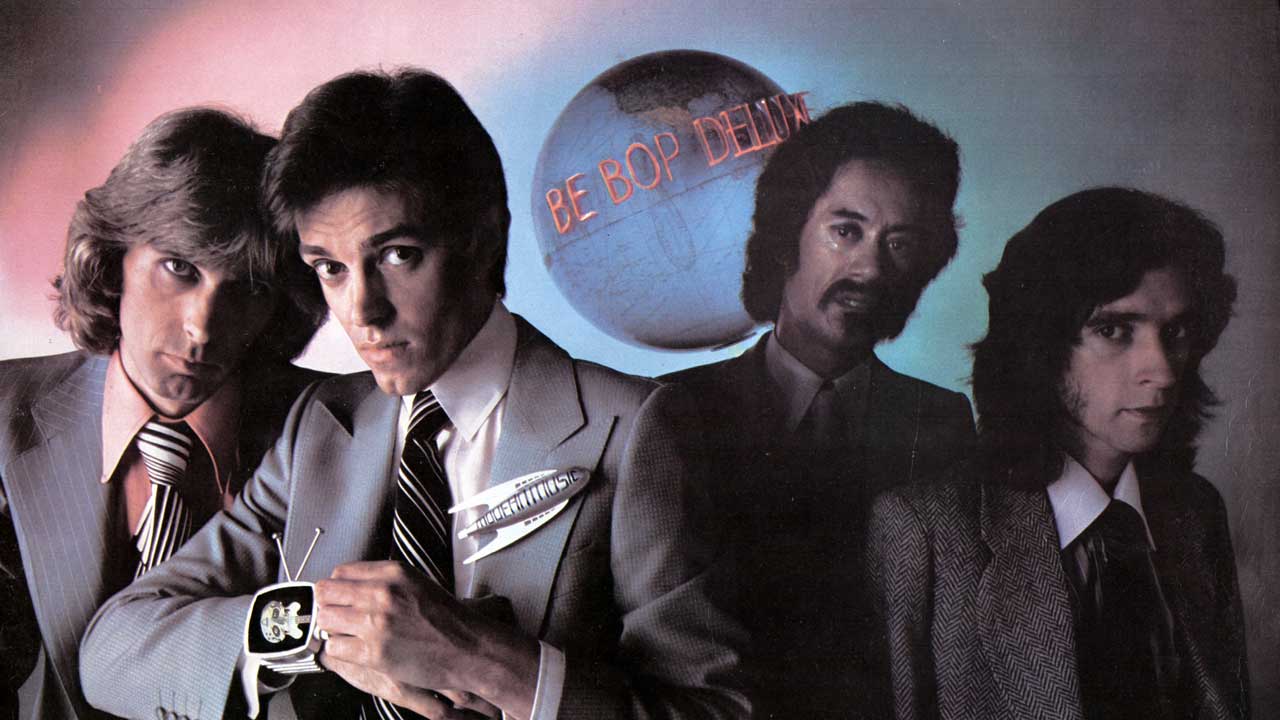

How do you solve a problem like Be-Bop Deluxe? That was the issue facing industry types and critics during the 1970s. The band were too savvy for rock’n’roll, too sleek for traditional prog, too complex for punk. They had hit singles they didn’t want, toured America with wholly incompatible acts and created pyrotechnical stage shows devised by the most reluctant of guitartoting frontmen. In short, they were the decade’s biggest enigma.

“We had some problems with the old guard in that things had to be clearly defined back then,” explains the band’s founder, guitarist, vocalist and songwriter, Bill Nelson. “We’d be pulling in all kinds of directions, not just from album to album or song to song, but within one piece of music. It made it very difficult for some people to grasp what we were about. We were a postmodern rock band.”

Across five studio albums, Be-Bop Deluxe blurred the battle lines between glam, art-rock and prog, offering a scintillating fusion that pointed to an unscripted future. Visionary works like Sunburst Finish and Drastic Plastic pre-empted the new wave of post-punk and beyond. Just as crucially, in Nelson they had the embodiment of the modern guitar hero; a riff lord of sophistication, guile and consummate ability.

A former art school student from Wakefield, his conceptual lyrics recycled pop culture in much the same way as those of David Bowie or Roxy Music, soaking up references from sci-fi, Pop Art and Expressionist cinema.

“The Pop Art thing was emerging when I was at college in the mid-sixties,” he says. “And that was part of the idea I had for Be-Bop Deluxe, to take the commercial pop and rock aspects and set them in a different context, to make people think and question it. Duane Eddy was the first guitarist I ever took notice of, then jazz players like Django Reinhardt and Wes Montgomery. The avant-garde came into play when I discovered John Cage and the Fluxus movement. So they were all swimming around in my head and somehow came to bear on the music.”

Nelson was working as a local government officer when he recorded his first solo album, Northern Dream, in 1971. A year later he and fellow employee Richard Brown started casting around for musicians to start a band. Be-Bop Deluxe quickly became known on the local club scene, although more for their visuals than for the music.

“It was never intended to be anything more than fun,” Nelson says, laughing. “We were playing in Working Men’s Clubs and pubs around Yorkshire, so putting on the glam-rock thing was kind of subversive. These hard, butch miners would be quite shocked by us. And we enjoyed that idea of getting up people’s noses. Instead of getting changed back into our street clothes at the end of a gig, we’d get in the van in our glam gear, with all the make-up still on, and stop off at a fish and chip shop. The looks we’d get were priceless.”

In the meantime, John Peel had become smitten with Northern Dream and played the whole record on his radio show in one go. EMI got wind of the album, too, and told Nelson they’d like him to re-record it with some choice session players. “At that point, I’d just started Be-Bop Deluxe and we were only about two weeks old as a group,” Nelson says. “I told them: ‘Actually, I’ve got a band now, so it’s not like that any more.’”

EMI were initially uncertain about Nelson’s new venture, but a storming gig at London’s Marquee in March 1974 persuaded the label to sign them up. Be-Bop Deluxe were promptly put on Harvest, the label’s progressive arm, and put in the studio to record their debut, Axe Victim. Largely comprised of songs road-tested for more than a year, the album veered from proggish reveries like Adventures In A Yorkshire Landscape to the hardnosed title track and winking sci-fi fantasias like Jet Silver And The Dolls Of Venus.

The band were packed off on tour for two months, supporting Cockney Rebel. “We went down really well with those audiences,” Nelson remembers. But sales of Axe Victim were modest.

For the follow-up, Nelson unveiled a slimmed-down new line-up, with bassist Charlie Tumahai and drummer Simon Fox. EMI duly teamed up Be-Bop with producer Roy Thomas Baker, who was then shaping the sound of another of EMI’s bands, Queen. But it wasn’t quite the harmonious union they’d hoped for.

“We recorded most of Futurama down at Rockfield Studios in Wales,” Nelson explains. “I was incredibly impressed by Roy Thomas Baker’s engineer, Pat Moran. I learned an awful lot just by watching him and seeing what he could do with the studio. But I wasn’t completely overwhelmed by Roy. He would sit in an armchair by the mixing desk and go: ‘Wakey wakey! Roly poly!’ And he’d organise food fights, which he seemed to believe was fun. He also set fire to the mixing desk by pouring sugar on it, then lighting it with a match. I thought: ‘This is public-schoolboy nonsense.’

“There was one occasion when we were at Sarm Studios in London, doing overdubs,” Nelson continues. “I asked for a bit more level for my vocals with the headphones and, ‘for a joke’, Roy turned it up full blast. I had to throw the headphones off, because my ears were nearly bleeding. I said to him: ‘Look, if you don’t stop this messing about, you’re off!’ I read an interview with him afterwards where he called me a prima donna. But this was our second album, and I really wanted it to be perfect, whereas this guy was just pratting about.”

Despite the less-than-ideal circumstances, Futurama, released in July ’75, contained several Be-Bop gems. Sister Seagull and Stage Whispers were fluid examples of Nelson’s foraging art, streaked with forceful guitar runs. Brightest of all was Maid In Heaven, a near-perfect single that deserved to be a monster hit.

“That’s definitely one of my favourite ever Be-Bop tracks,” Nelson says. “It’s so succinct.”

Be-Bop Deluxe were back in the studio by the end of the year, this time with keyboard player Andy Clark on board. Keen not to repeat the mistake of Futurama, Nelson insisted that he produce the album himself this time. EMI, in turn, forced a compromise, stipulating that he team up with Abbey Road engineer John Leckie, who was ready to make the leap to producer.

“John had actually engineered some of Axe Victim,” Nelson recalls. “We had lunch together in St. John’s Wood and decided we could do it between us. It turned out to be a really good working relationship.”

The resulting album, Sunburst Finish, issued in early ’76, was a masterpiece. Nelson had hit an early peak as a songwriter, displaying a renewed level of artistry and confidence, while the band were a perfect compliment to his formidable guitar playing.

As befits the final piece of a guitar-nerd trilogy set up by Axe Victim and Futurama, Sunburst Finish includes a searing tribute to Jimi Hendrix on the eloquent Crying To The Sky. “I’d seen Hendrix on Ready Steady Go!, making his first TV appearance in this country [December 16, 1966], where he played a guitar solo with his teeth,” Nelson remembers. “It was a Friday night, and I met my mates afterwards at the local Mecca dance hall. We just sat and talked about it all night, because it was so mind-blowing.”

Sunburst Finish also yielded a Top 30 single, Ships In The Night. With its airy synth and reggae-ish lilt, it was written partly to placate EMI, who’d asked him for anything that might sound like a pop hit. “I kind of wrote it tongue-in-cheek, thinking that this wasn’t great,” Nelson says, with a tinge of regret.

“But it was a hit. It has its place, but it’s probably my least favourite Be-Bop Deluxe number. I thought that maybe I hadn’t completely stuck to my principles with that song. At the same time, it did a lot of good for us. It opened up a certain area for the band, and people started to investigate the album as a result.”

Sunburst Finish itself went Top 20 in Britain, bolstered by an extensive tour on which Nelson’s conceptual stage ideas reached full fruition. Life In The Air Age was accompanied by footage of Fritz Lang’s pre-war sci-fi classic Metropolis. There were tracer lights, transparent tubes from which the band would emerge, and vast projections of pulp magazine covers, while Nelson had become a stage guitarist to equal any of his contemporaries. The show climaxed with him striking a pose with guitar aloft, similar to the one by the nude model on the album’s sleeve, before it burst into sacrificial flame.

“We had a guitar made for us – a cheap one, but it looked like my Gibson – and rigged by a special effects department to put an incendiary device in it,” Nelson explains. “It’d worked fine in rehearsal, but on the first night, for some reason, it didn’t light when I flicked the switch during the gig. So my guitar tech took a leaf out of Hendrix’s performance at Monterey by pouring lighter fluid all over it and setting it on fire. We did it at the Drury Lane Theatre Royal and got banned.”

Equally memorable, although for a different reason, were the band’s first tours of the US that year. As a measure of EMI’s inability to fathom the band, Be-Bop Deluxe were sent out with Lynyrd Skynyrd, Ted Nugent and Blue Öyster Cult.

“Skynyrd were really good to us,” Nelson recalls, “but the others were difficult. We were basically blanked by Ted Nugent and his people. Nugent was a strange guy. When we were between gigs on planes and the rest of it, his whole look would change. He would put glasses on and hunch up, like a little old man. Then he’d get on to the stage and his hair would be wild, and he’d be jumping over the amps. It was mad.”

Back home, the breakthrough success of Ships In The Night and Sunburst Finish had given Be-Bop Deluxe a wider audience. Follow-up album Modern Music, released in September ’76, stopped just shy of the Top 10. But Nelson was ambivalent about his new-found status as a commercial proposition. Frustrated with audiences who just wanted to hear songs from Be-Bop’s back catalogue, rather than anything forward-facing, he decided to move on.

“I’d wanted to disband Be-Bop after Modern Music,” he reveals. “I’d suggested to our management company that I wanted to form a different band and try to do something else. I already had some ideas in mind. But I was persuaded by management and the record company to just make one more album, then they’d let me go. So we did Drastic Plastic.”

Released in February 1978, the album signalled a marked shift in the Be-Bop sound. The songs were more urgent and direct, with a greater emphasis on electronica and studio innovation. Many of its embryonic ideas would feed into Nelson’s next project, Red Noise.

“There was certainly some of that gated snare drum sound, which had appeared on Bowie’s stuff, on Drastic Plastic,” he explains. “And we were creating tape loops of drums and so on. It also featured one of the first guitar/synthesisers in the country, a thing called the Hagström Patch 2000, which you could use to trigger notes.”

His mission complete, Nelson then broke up the band.

These days, the 70-year-old Nelson seems busier than ever, maintaining a solo career that runs into dozens upon dozens of albums. He releases several a year (through his Dreamsville website) to a devoted fan base who’ve mostly been with him since the Be-Bop days. His latest is the triple-disc Auditoria, and he has others ready to go. “I think I’ve got it down to ten unreleased albums at the moment,” he says in his soft Yorkshire brogue, at his home studio just outside York.

Nelson admits to not being fully conversant with current music trends, although fans assure him that the music he made with Be-Bop Deluxe hasn’t dated much, if at all. A spanking new remastered Deluxe Edition of Sunburst Finish, with bonus tracks and live tracks from the BBC archive, plus videos, has afforded him the opportunity to look back at his 70s career. It’s not something he does readily, preferring instead to push on with his next project, but it’s a legacy that he’s quietly proud of nonetheless.

Treasured by guitarists such as Stuart Adamson, John McGeoch and Steve Jones back in the day – and a key influence on a newer breed of left-field practitioners that includes Earth and Sunn O))) – Nelson remains an atypical axe hero.

“To be honest, I’ve always felt more comfortable as a studio person, rather than on stage,” he reflects. “I’ve loved the guitar ever since I was ten years old, when I first started playing it, and it’s such a big part of my life. But it wasn’t just about playing riffs, there was other stuff going on as well. I did want success for Be-Bop, and I hoped it would be more on our terms. It was all about taking you on an adventure.”

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 258, published in February 2019. Bill Nelson has released another 15 albums in the five years since.