The numbers attending the tangihanga for Kīngi Tūheitia Pōtatau Te Wherowhero VII attest not only to the enduring significance of the Kīngitanga movement, but also to its political relevance at this point in Aotearoa New Zealand’s history.

Tūheitia, the seventh Māori monarch, died on Friday at the age of 69. Prime Minister Christopher Luxon said he was “somebody who tried to pull everyone together – Māori and non-Māori”.

Luxon’s government, of course, has been accused of doing the very opposite through policies designed to limit Māori influence in public life. With the ACT Party’s hugely contentious Treaty Principles Bill about to be introduced, it is the risk of pushing people apart that worries many.

The Kīngitanga’s own founding principle of kotahitanga – unity – is therefore as relevant as ever.

Kotahitanga

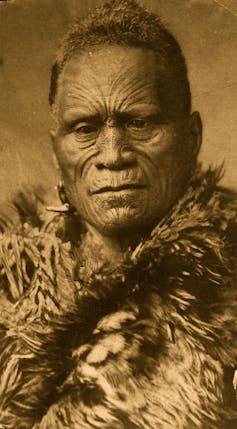

Other than parliament, the Kīngitanga (King Movement) is New Zealand’s longest continuing political institution. Formed in 1858, it predates political parties. It was founded with the unifying “korowai” (cloak) of stopping the colonial sale of land, ending inter-tribal warfare, and preserving Māori culture.

Although not all iwi (tribes) joined the movement, its original purpose of stopping colonial expansion remains universal, and makes it nationally significant. The hui-a-iwi (national meeting) Tūheitia called in January to resist the new government’s policies to diminish the role of te Tiriti o Waitangi (Treaty of Waitangi) attracted 10,000 people.

Shortly afterwards, the prime minister gave a firm commitment that his National party would not support into law its coalition partner’s Treaty Principles Bill. More recently, the Waitangi Tribunal found the bill was “unfair [and] discriminatory”.

So, too, was the 1863 invasion of the Waikato, which saw the confiscation of 1.2 million acres of Māori land. For the government of the day, resistance amounted to rebellion against the sovereign authority of the Crown.

Invasion and resistance

In 1884, the second king, Tāwhiao, travelled to London to seek restitution and “renew the words” of the Treaty. Queen Victoria wouldn’t meet him. The British Colonial Office said land confiscation was a matter for the New Zealand government.

In doing so, Britain rejected the idea of te Tiriti being a personal relationship between Victoria and the chiefs who signed the agreement, after English missionaries convinced them this was its intent.

While it’s a sharply contested policy, it’s perhaps not surprising Te Pāti Māori proposes severing New Zealand’s connection with the British monarch so that te Tiriti may be honoured according to the party’s interpretation of the agreement.

But it is because the Kīngitanga stands apart from party politics that it remains influential, with kotahitanga its essential and enduring ambition.

Reparation and redress

Partial restitution for the Waikato invasion was achieved in 1995 with the Waikato Raupatu Claims Settlements Act, which was symbolically given royal assent by Queen Elizabeth II.

The act’s material substance flowed from admitting the Crown’s “unconscionable” conduct. It accepted the confiscated lands made a significant contribution to the wealth and development of New Zealand, while Waikato iwi were deprived of the benefit of their lands.

The NZ$170 million settlement was a fraction of the land’s estimated value in 1995 of $12 billion. So it wasn’t a fair and equal act of reconciliation. Unity was achieved, perhaps, through Waikato generosity.

Nevertheless, further payments meant the settlement was increased to ensure relativity with later settlements with other iwi. In 2022, total payments had reached $390 million. Post-settlement investments had seen the Waikato asset base grow to $2.2 billion by 2023.

Such Māori success is important, and provides a foundation for Tūheitia’s call for unity.

Leadership beyond parliament

Celebrating the 18th anniversary of his coronation last month, Tūheitia addressed the contemporary meaning of kotahitanga:

Our kotahitanga shouldn’t be focused on fighting against the government. Instead, we need to focus on getting in the waka and working together. Mana motuhake has room for everyone.

Significantly, he added:

I don’t want politicians to lead the conversation about nationhood.

Leadership beyond conventional party politics may take some of the tension from contemporary Treaty policy debates.

Only last week, the prime minister objected to a ten-year-old Waitangi Tribunal finding that Māori did not cede sovereignty to the British Crown under te Tiriti, telling parliament, the “Crown is sovereign”.

This was meant as an assertion of colonial authority – as if government and Māori can’t have political authority at the same time. As if mana motuhake – autonomy and self-determination – doesn’t allow “room for everyone”.

If kotahitanga is the objective, there must surely be space for everybody to say, as Tāwhiao did, “Maku ano e hanga toku nei whare” – I will build my own house.

Speaking about the Treaty Principles Bill at the hui-a-iwi in January, Tūheitia said, “There’s no principles, the Treaty is written. That’s it.”

The coming weeks and months will test that view – and demonstrate the place of the Kīngitanga as a political and cultural institution outside parliament and political parties. The new monarch’s job will be an important one at an important time in the New Zealand story.

Dominic O'Sullivan does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.