Where better to begin a morning of touring the old neighborhood than the outsized parking lot of a tiny … wait, is this a Chinese restaurant or isn’t it? Because 63rd Fried Rice, our arranged meeting spot, still has an old sign up top that says Parisse’s Drive-In and boasts of copious Italian meats. So which is it?

“Parisse’s,” Ron Coomer says after steering into the lot in a black BMW 750i. “It’ll always be Parisse’s.”

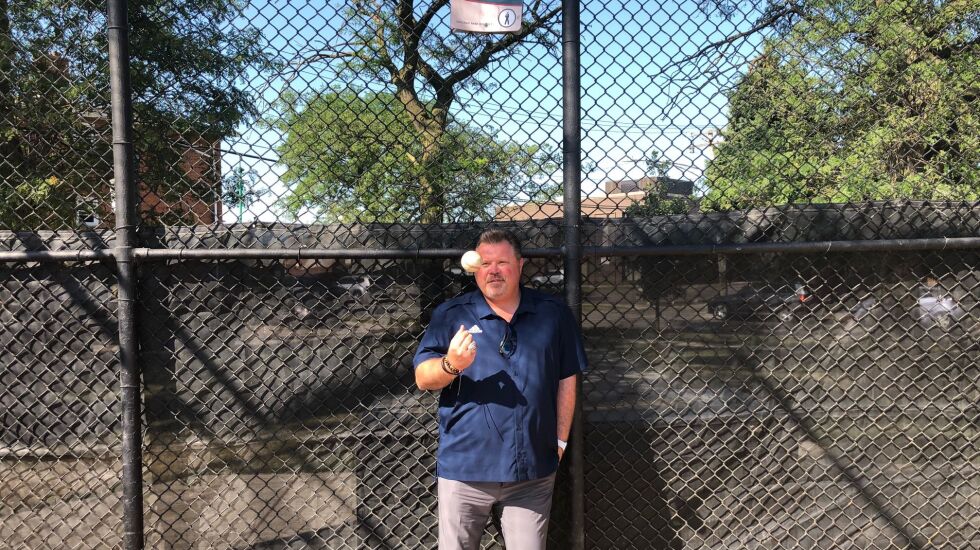

It’s not Parisse’s anymore, but his point is well taken because 63rd Street and Melvina on the Southwest Side might as well be known as Coom’s Corner. The Cubs’ radio analyst (since 2014), former Cubs player (in 2001) and lifelong Cubs fan is from this neighborhood — he calls it Garfield Ridge, though technically it’s Clearing — and Parisse’s, along with Vince’s Pizzeria directly across the street, often was its epicenter. A hungry kid couldn’t miss with a beef sandwich on one side of 63rd or a tavern-style pie on the other.

Coomer’s dad, Ron, was good pals with Parisse himself in the 1970s, and a few of Coomer’s cousins worked behind the counter. Two decades later, whenever Coomer’s Twins would swing through town for a series against the White Sox, the infielder would order 70 sandwiches to Comiskey Park for teammates and all the cops stationed there. A clubhouse attendant would wheel them through the room in a laundry cart to a hero’s welcome.

“Great memories,” says Coomer, 55.

But we haven’t even gotten started. We can see Kinzie Elementary, Wentworth Park, Minuteman Park and the other stomping grounds of a nascent ballplayer soon, but first we have to feel the dirt of Hale Park’s Field 4 under our feet.

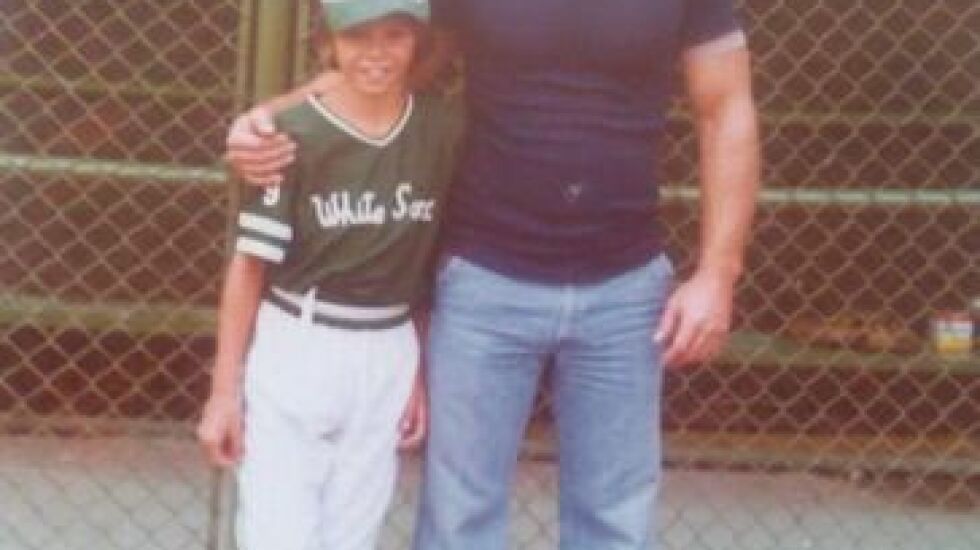

From 8 to 12 years old, Coomer and his dad played baseball together hundreds of times. Ron Sr. would come home from a local truck-driving job out of Argo to find his only son, one of two children, wearing one mitt and holding another. To Hale — always Field 4 if it was open — they’d go. Coomer, a Clear Ridge Little Leaguer at the time, would grab his bat, hit a few baseballs, chase them down and do it all again for an hour or longer. Then he’d take his glove and run as deep into the outfield as his dad would let him before fielding fungos, and this would go on for every bit as long.

And could Dad ever send them soaring. After two years at Lindblom, Ron Sr. had given up on playing sports to work at a gas station on 63rd and Narragansett because he needed the money. But he later boxed in the Air Force and became a serious bodybuilder. He was only 5-9, but he was a powerhouse and some kind of an athlete.

“That’s a good way to teach a kid to not be afraid of the ball,” Coomer says.

His dad wouldn’t have allowed it. He was a hugger, but he could be hard and he expected his boy to drive the ball, to make the catch, to hit the glove with his throws and definitely not to make any excuses. Coomer never stopped wanting to impress him.

“He was a good coach,” Coomer says. “He was part psychologist, he was a tough guy and he wanted to make a tough kid in sports. My toughest competition until I was probably through high school was right here.”

Staring in at the batting cage from where third base would be, Coomer goes silent for a while and begins to cry. He hasn’t been on this field since he was a kid. Being here and talking about his dad — who was larger than life — is too much.

Ron Sr. died of a heart attack at 59 in 2003, Coomer’s final year in the big leagues. Coomer would give anything for one of those hugs, like the one he got the first time one of his dad’s pitches got away and found the boy’s knee. An ice cream at Parisse’s helped.

Back at the house, mom Linda asked her husband, “What did you do to him?”

“He’ll be all right,” was the answer.

WE ARE STANDING ON CENTRAL AVENUE where 59th Street would meet it if it weren’t cut off by Minuteman Park. Call it another of Coomer’s “corners,” because here he would stand as a boy, in the gravel at the park’s edge, and put the “fun” in “fungo” by hitting rocks into what then was a much smaller, less-busy Midway Airport. The usual target for battering was an empty hangar. At least, he thought it was empty.

It was a mostly pleasant childhood for Coomer, born in 1966, who last lived in the modest bungalow at 5734 S. Massasoit Ave. in 1980. Coomer and sister Gina had many friends and cousins around, and nobody loved sports more than the short, scrawny boy who would go on to play nine seasons with the Twins, Cubs, Yankees and Dodgers.

One of Ron Sr.’s friends worked at the nearby Tootsie Roll plant, and Coomer would grab a handful from the bag that was always in the house, chew them and spit brown streaks as he played baseball. (Today, he tosses them to fans from the radio booth at Wrigley Field during the seventh-inning stretch.) After the famous blizzard of 1979, the Coomers’ backyard was unusable for a month; the football and hockey in the street, though, were legendary. An uncle had a snow plow on his truck, and Coomer would ride along as they plowed church lots, Parisse’s, Vince’s and other spots, with Coomer scrambling out of the vehicle with a shovel to get the unreachable areas.

“Great memories,” he says again.

But Ron Sr. was beginning to struggle with mental illness that only would get worse, and life on Massasoit became uncomfortable for all. Ron Sr. turned to self-medicating.

“How do you treat that?” Coomer says. “Back then, you treated it at a bar and you’d drink, and that’s how he treated it. It was sad, you know?”

Coomer’s parents split up, got back together, split again and eventually divorced before Coomer finished high school. Coomer’s high school time was complicated; he went to St. Rita as a freshman, Lockport as a sophomore, St. Rita again as a junior and Lockport again as a senior. In the Lockport years, he lived with his maternal grandparents in Homer Township. By now, he was playing travel ball out of Homer and coming into his own as a player.

Ron Sr. was getting help — often with his son in tow — at a VA hospital, first for the drinking and eventually for a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. But he never took to the help, which is to say that he resisted it. When he felt better, he said everything was fine. The good times never lasted, and the bad ones persisted until the end.

“He wasn’t the type to see it,” Coomer says. “It wasn’t in his character. He would say, ‘Boom, I’m good,’ and then it would come back.”

Coomer never felt afraid of his father, but seeing the man he idolized fall apart was unnerving and traumatic. Coomer took it on stoically, rarely talking about it and, to this day, never seeking professional help himself. He admits he isn’t sure that was wise.

“Here you have a good situation, a good family, and it just went south,” he says. “Somebody asks me how things are going? Great, because they had to be. I couldn’t let it break me down, because then what do I do?”

Asked if he pays enough attention to his own well-being, Coomer sits behind the wheel silently for a bit.

“You don’t want to fall into the same traps,” he says. “My family, we’ve all had that in some way, shape or form. I look at that and go, OK, you watch your drinking. I’ve never been into drugs in my life, never smoked marijuana. I was an athlete. I’m not saying that’s good or bad, but I just never did it. But always in the back of my mind, I’ve had some big weeks where I’ve had to calm down and make sure [I’m] OK. I would say there were times in my life I was a little over the top with my life, but then you get a wake-up call and back right off.

“For me, there’s always been something burning in me to want to do what I’m doing. I never wanted to do something that was going to jeopardize baseball or my life, going to the ballpark or how people viewed me. There’s got to be a line.”

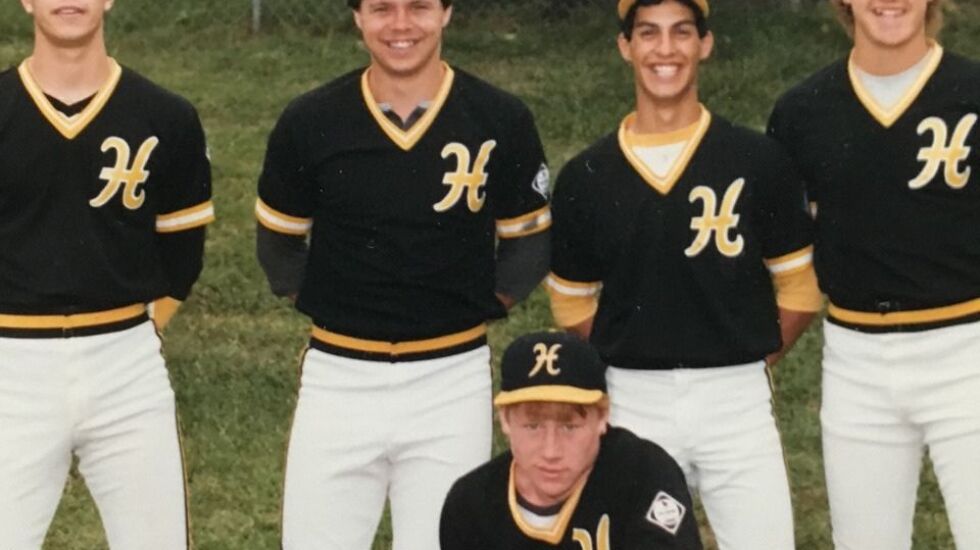

COOMER WASN’T ON ONE OF THE CORNERS — third or first, which he played in equal measure as a big-leaguer — in his formative years of baseball. He was a shortstop, which Jeff Schultz learned the hard way when Coomer showed up to play travel ball in Homer. Schultz, who would go on to play at Illinois, got bumped over to third almost immediately by the spindly kid who would become his best friend for life.

They met in a parking lot at 13, when a coach asked which parents could drive the boys a few miles down the road for a game. Coomer, who’d pulled up in a black Cadillac — yes, he was behind the wheel — raised his hand. All these years later, Schultz insists Coomer was driving solo. Coomer says his old man must have been riding shotgun. Either way, Schultz got in.

“People ask what differentiated Ron from a lot of guys,” Schultz says. “No. 1, it was his mental toughness. He had a lot going on off the field with his family situation, but once he got between the lines, he was the most mentally focused person I’ve ever met in my life. And No. 2, he could hit a ball like nobody’s business. When he hit it, it wouldn’t just go — it would keep going.”

Coached by Pete Fera, a kind man, Coomer took off, leading his teams to the Colt and Palomino World Series.

“He was good, and he knew it,” Fera says, “but he never put on fancy shows. He was too nice and thoughtful for that.”

Jim Hall, a former coach at Lockport who, through a connection, would help Coomer get to Taft (California) College, remembers Coomer’s leadership. As a senior, Coomer ran laps with a misbehaving teammate and, in that simple interaction, changed the kid’s trajectory. The Porters made it to the state quarterfinals, a rare feat for the program.

We’re at Lockport now, where Coomer’s name is on the outfield wall. A camp for incoming freshmen is underway, and coach Scott Malinowski asks Coomer to address the hopeful players.

“You never know who’s going to be the next big-league baseball player, and this is where it starts,” Coomer tells them before brandishing his 2016 World Series ring to their wide-eyed delight.

When Coomer got his driver’s license as a junior, he was 5-8 and 150 pounds. Less than a year later at his preseason physical, he checked in at 5-11, 185. A Royals scout started coming around, leading Coomer to believe he might have a chance at something big.

At Taft, Coomer — so athletic he could dunk a basketball — was the fastest player on a team that would see half a dozen players drafted. But he tore an anterior cruciate ligament and played his sophomore season in a brace, nevertheless bombing away and becoming a junior-college All-American. He never would get his speed back. The A’s drafted him in the 14th round in 1987, and a long minor-league journey began. Coomer didn’t get the knee repaired until after his second year of pro ball, still early in an odyssey during which he was traded twice and wouldn’t reach the majors until he was 28.

It turned out he could handle himself quite well at the top level, because once he went up, he never went back down. With the Twins in 1995, he hit his first home run off Randy Johnson.

“I didn’t look at him,” Coomer says. “I was like, ‘Hell, no, I’m not going to piss him off.’ ”

It was one of a collection of storybook firsts. Later in 1995 — in his first of six seasons with the Twins — he hit his first Chicago homer off the Sox’ Kirk McCaskill, with more than 50 friends and family in the stands cheering him on. In 1999, he hit his first homer at Wrigley, off Terry Adams, a boyhood dream come true. In 2001, he bombed away at Wrigley for the first time as a Cub, the team he loved so much it occasionally moved him to tears. A year later — in his first at-bat as a Yankee — he went yard off the Rays’ Wilson Alvarez, the 86th of his 92 career homers.

Ron Sr. was a Yankees fan, but he wasn’t well enough to be in the Bronx that night. Linda and her husband, Bob, were there, along with some uncles and girlfriend Paula, whom Coomer would marry in 2003. Coomer called his dad, who’d watched the game from Florida, and for a while the two of them just laughed.

Coomer is tearing up now.

“My dad said, ‘You’re a Yankee now,’ ” he says. “I’ll never forget it.”

“COOM’S CORNER” WAS THE NAME of a radio show Coomer co-hosted in Minnesota during his time with the Twins, and he would work 10 years in media there after his retirement, doing all sorts of things. His favorite was a radio show on which he talked sports — not just baseball — and played records.

“I was a DJ!” he says, laughing at the sound of it.

But the real music to his ears came late in 2013, after he listened to a voicemail from Cubs radio play-by-play man Pat Hughes. Coomer was doing television work on Twins broadcasts, though not in the booth, at the time.

“You know the Cubs job is open, right?” Hughes said when Coomer called him on the ride home from the ballpark.

Coomer was flummoxed. He and Hughes had gotten to know each other in 2001, but it’s not like they were close friends. There had to be a line of ex-Cubs with longer histories with the team who hoped to replace Keith Moreland, and, in fact, there were a few already under consideration for the job. Why Ron Coomer?

“I’d like for you to be my partner,” Hughes said.

The next day, Coomer met with Cubs executives. The job was his if he wanted it.

“I needed a new partner,” Hughes says, “and, literally, he was the first person I thought of.”

Hughes never had forgotten Coomer’s affable, earnest demeanor or his hard-working nature from that 2001 season. On buses and airplanes, Coomer had gravitated toward Hughes, and the men had talked baseball in a manner that just seemed easy and perfect. It continues to this day.

“Literally, we have never had one bad moment between us,” Hughes says. “Not one. Good teams and bad — and the pinnacle of 2016 — he has been so easy to work with, so insightful. He can articulate things better than the guy who comes by it naturally, and I think that’s because he had to work and grind for everything he has.”

Says Coomer: “We’re friends, right? But we’re very different, and I think that’s a good thing. We’re complementary in the differences we have. And we’ve never had a cross word in nine years — nothing, zero.”

Paula — a native Minnesotan — didn’t love the idea of leaving, but she came around, and being home again has been one of the greatest joys of Coomer’s life. Never more so than on the night the Cubs beat the Dodgers to win the National League pennant in 2016, which sent Coomer and some of his oldest friends to the rooftop of Murphy’s Bleachers for cigars, beers and voluptuous pours of Tito’s vodka. It was Coomer’s favorite night in Cubs history.

Six seasons later, he is less than thrilled with where the Cubs are at. The team trading Yu Darvish and giving up on Kyle Schwarber put him on guard, but what came next — so long, Anthony Rizzo, Kris Bryant and Javy Baez — was a lot to swallow.

“I was a lifelong Cubs fan and a Cubs player, and we won a World Series with those guys — and it just gets blown up in a 48-hour period?” he says. “But I guess you knew it was coming because you don’t let Kyle and Darvish go before that, if not. It wasn’t a big shock, but it was rough.”

If the Cubs made one mistake, Coomer believes, it was signing all three of those core stars to contracts that expired simultaneously.

“I think if the Cubs had it to do over again, they certainly wouldn’t have done that,” he says. “That was a tough one, right? Your chips are all in, and then you pull them all out, right? I’m sure that wasn’t something they wanted to have happen.”

But complaining, he is not.

“I get to go to Wrigley Field every day,” he says. “I have the greatest job in the world.”

THERE’S NOTHING FANCY ABOUT the Coom’s Call burger or Ron’s Chicken Sandwich at Coom’s Corner, guess-who’s restaurant in Lockport. But they’re big, they’re good and they damn sure get the job done. Sound familiar?

“I guess that’s me, isn’t it?” Coomer says, hunkering down over a plate served by one of his cousins. “What you see is what you get. I’m a Chicago kid.”

Speaking of which, there’s a game at Wrigley tonight, and Coomer has to shove off for the city soon. What else is there to discuss?

A lot, it turns out. In no particular order: many nights of Springsteen; 13 knee surgeries; a right knee replacement in 2015 and a left one coming up soon; years of trying unsuccessfully to start a family; teaching history and coaching baseball, which he would’ve done if he hadn’t made it as a player; getting back on the field and coaching, which he swears he’ll do before it’s too late; Rizzo’s friendship; Bryant’s kindness; Jon Lester’s quiet, unfailing generosity at restaurants; and changes in swing plane absolutely ruining hitters.

When it comes to launch angle, Schwarber just might be the one that got away.

“To me, with the right people around him coaching-wise keeping his swing on a level plane, Kyle might be one of the top three hitters in our league,” Coomer says. “I just think this new theory of hitting hasn’t done him any favors. I looked at him when he came to the Cubs, and I went, ‘Wow.’ Right up the middle, line drives to left, then they throw the ball inside, and he hits a bomb. But then everything starts with trying to elevate the ball, and a guy I thought would hit .300 is hitting .200.”

Here’s a late curveball for Coomer, who played in the heart of the steroid era: Did he or didn’t he?

“I didn’t, I can tell you that,” he says. “The way you know someone didn’t is now that we’re older, we age like everybody else. We get bigger and heavier, and your body hurts, and you can’t move around anymore and you’re getting knee replacements and things.

“But I don’t regret it. I could not justify putting something like that in my system, and believe me — I was tempted to the extreme of it. Because you saw it every day and knew it was going on, and you’re not competing equally; you’re just not.”

By the time Coomer was in his last season, a Dodger, he was unable to play two days in a row. Only after he hung it up did he find out he’d played in 2003 on another torn ACL. He’d squeezed every drop out of what he had, and that’s satisfying to this day.

“ ‘Content’ is not the right word — I’m happy in what I’m doing,” he says. “I’m going to Wrigley Field, the place I grew up, the place I went to with my dad at 4 years old and ate a hot dog.”

Ron Sr. was correct all those years ago: His boy would be all right. And Ron Sr. would’ve been extremely proud. It wasn’t the tough man’s style to express such a thing to his son, but this is not up for debate.

“He told everybody else,” Coomer says. “He didn’t tell me, but that was OK. I knew.”

There are tears again.

“I think of him now, with me being here, back home, the Cubs winning the World Series, my job, you know?” he says. “I know this: If he were here and OK — if he could see all this — God, it would’ve been fun.”