In April, archaeologists excavating at La Chapelle-des-Fougeretz, in Britanny, France, announced that they had discovered a large Roman temple, dating between the late first century BC and fourth century AD. They speculated that it had probably been used by Roman soldiers for hundreds of years to pay homage to Mars, the god of war.

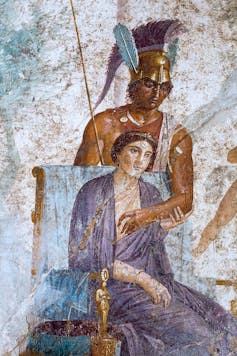

It was the discovery of a fine bronze statuette of Mars that suggested the temple may have been a shrine to the god. But the site also had clay figurines of Venus and the mother goddesses, leading to uncertainty about which deity was worshipped there.

Two buildings were at the core of the site – a square within a square, one slightly smaller than the other. This design is typical of Romano-Celtic temples (found in modern France, parts of Belgium, Germany, Switzerland and the north-west provinces of the Roman Empire).

Scholars of ancient religion in the Celtic north west regions of the Roman Empire (of which ancient France was a major part) used to regard a double temple arrangement as a dedication to a divine pair, one male and the other female, such as Apollo and Sirona or Mercury and Rosmerta.

The female names were usually derived from Celtic languages, while the male gods were from the classical Graeco-Roman pantheon, implying some sort of “marriage” between them and by extension, the synthesis of local culture with that of Imperial Rome.

But this theorising was a reflection of 19th and 20th century colonial thinking. Present day experts have found that ancient people chose their forms of worship, rather than having religions imposed upon them.

Ancient communities could preserve Iron Age traditions or adopt aspects of Roman classical religion. This is reflected in the archaeology of their temple sites.

Some had wooden buildings and few, if any, featured classical images of gods. Others, particularly in the towns, opted for a more full on Roman style of worship, even if the old native traditions still underpinned the rituals.

How the gods were worshipped at these temples

Looking at excavations of temples in Gaul (modern France, with parts of Belgium, Germany and Switzerland) and Britain, it is striking that the architectural form is often quite standardised.

The temples are usually in the Romano-Celtic design, with a small square central tower surrounded by a portico (a row of evenly spaced columns with a lean-to roof up against the central tower).

The sculpture, inscriptions, artefacts and sacrificial remains are, however, widely variable. They reveal the development of a highly localised suite of ritual activities that varied significantly from one temple to another.

Equally striking is their long-term stability. It seems that once established (either in the early Roman period or sometimes in the pre-conquest late Iron Age), rituals quickly settled down into patterns that continued, at some sites, for centuries.

The end usually came in the late Roman period, as pagan shrines were abandoned in the face of the expansion of imperially promoted Christianity.

Mars, Venus and the mother goddesses (and possibly others not yet discovered) were probably the deities included in the rituals observed in the two shrines and the equally important open air courtyard in which the shrines stood.

It is in the courtyard that much of the public ritual, such as sacrifices, would have taken place. From this perspective, archaeologists cannot be sure that, for instance, the bigger temple was for Mars and the smaller one for the female deities.

We do not know the exact purpose of the temple buildings themselves. The central cella area is usually thought to be a “house for the god”. Plinths are sometimes found within them, suitable for a statue or other cult idol.

The surrounding porticoes are secondary features, as some temples start life as a simple square structure and the portico is added later. At the site of Pesch, near Aachen in Germany, the portico of one of the two temples had altars to the Matronae goddesses (a variant on the mother goddesses). The cella, meanwhile, contained a statue of Jupiter.

It looks as though the porticoes developed as a shelter for votive offerings, up against the central shrine building.

Many gods in the sacred landscape

At many temples, a wide variety of images and god names have been found.

At Gerolstein, near Trier in Germany, there was Minerva, Venus, Mercury, Bacchus and Hercules. At Le Hérapel in the Moselle region of France, there was Sol, Luna, Mercury, Bacchus, Hercules and Epona. At the Bregenz temple site in Austria, there is an inscription to “the gods and goddesses”, showing that many deities were worshipped collectively.

In Britain, the temple at Lamyatt Beacon, Somerset, had a cache of statuettes of Jupiter, Mercury, Mars, Minerva, Hercules and a Genius. Similar hoards of figurines have been found elsewhere in the province.

Clearly, the “poly” in polytheism meant just that – many deities, worshipped together. There may have been a main or original god or goddess at many temple sites, but there was a clear tendency to worship a range of deities, possibly accumulating new idols over time.

The broader sacred landscape adds clarity to the finds at La Chapelle-des-Fougeretz. The site is complemented by another temple at Mordelles, to the west. Both were within easy reach of the Roman city of Rennes and it is quite possible that they were linked to the town by processional or pilgrimage routes.

In the heart of Rennes itself, evidence for worship of Mars is strong. All three places may have formed the sacred landscape of the citizens, in the form of processions and seasonal festivities.

It is tempting to think of ancient religion in monotheistic terms – one temple, with one god. But the evidence from the Romano-Celtic regions of the empire suggests otherwise. It is much more genuinely polytheistic. Several deities were worshiped at most temple sites, with strong regional networks linking many gods and goddesses together.

Tony King does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.