The world flunked its big chance to use the Covid pandemic to become more sustainable. Now it must use the twin perils of war and inflation to try again, writes Rod Oram

With each fleeting day, the global clash between humanity’s past and future grows ever more intense, ever more consequential.

We blew our chance to do better after Covid. The 50 largest economies spent US$14.6 trillion on fiscal and recovery efforts up to this time last year. But they used only 2.5 percent of the money to make themselves more sustainable, the UN Environment Programme has reported.

No surprise, much of the money made matters worse, most crucially in wealth inequality, housing unaffordability and greenhouse gas emissions. New Zealand is one of the many, and more extreme, examples around the world.

Now, war and inflation are giving us another chance to create a better future. Will humanity take it? Will we try here in Aotearoa?

Many aspects of our lives are on the line. From prosperity to security and sustainability. In all senses of those words - economic and ecological, social and cultural.

This column will focus on only two – mainly energy, and some on food.

Fossil fuel prices are soaring for three main reasons. Strong recovery in demand as Covid wanes and economies revive; under-investment in fossil fuel production because, for example, US banks and investors were very badly burnt by the prior bust in fracking; and Russia’s war on Ukraine.

So now there’s a great race on between dirty old fuels and clean new ones. If old fuels win, we’ll wipe out our slender hope of forestalling catastrophic climate change. If new energy wins, we have hope of keeping the rise in global temperatures to a manageable 1.5C.

Oh, and don’t forget the co-benefits along the way. Such as far cheaper power; or no more market power wielded by autocratic regimes like Russia, Saudi Arabia, Venezuela and the worst of the Gulf states; or no more fossil fuel political corruption, even in the US. The latest evidenced of the latter being the role of coal in the business and political career of Joe Manchin, the one-man block to climate legislation in the US Senate, as a New York Times investigation has just revealed.

Some of coal’s other old friends are back in force too. The global banking sector has doubled its funding for coal to US$9.9 billion in the first quarter of this year, compared with a year earlier, with Chinese projects being the biggest recipients, Bloomberg reports.

So much for the pledges by many global banks to curb their lending to the sector. After a sharp cutback in 2016, financing volumes recovered by 2018. On their current trajectory they could set a new peak this year.

Last year saw coal powered electricity generation set a global record, Ember, a UK energy transition NGO, has just reported. It took a 36 percent share of overall electricity generation. This coal rebound pushed electricity sector CO2 emissions to an all-time high, up a record 7 percent year-on-year.

But Ember’s analysis also reveals a counter, and positive, trend. Clean electricity sources, including solar, wind, hydro, nuclear and bioenergy, generated a total of 38 percent of the world’s electricity last year, beating coal. Rightly, though, Ember flagged some sources of bioenergy as “very high carbon.”

Solar and wind were the fastest growing sources of clean energy, jumping 23 percent and 14 percent respectively. They are now cheaper sources of electricity than coal, Ember says. Their share of global generation has now doubled since the signing of the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate. If their 10-year average compound growth rate of 20 percent was maintained to 2030, the 1.5C goal by 2050 would become more realistic.

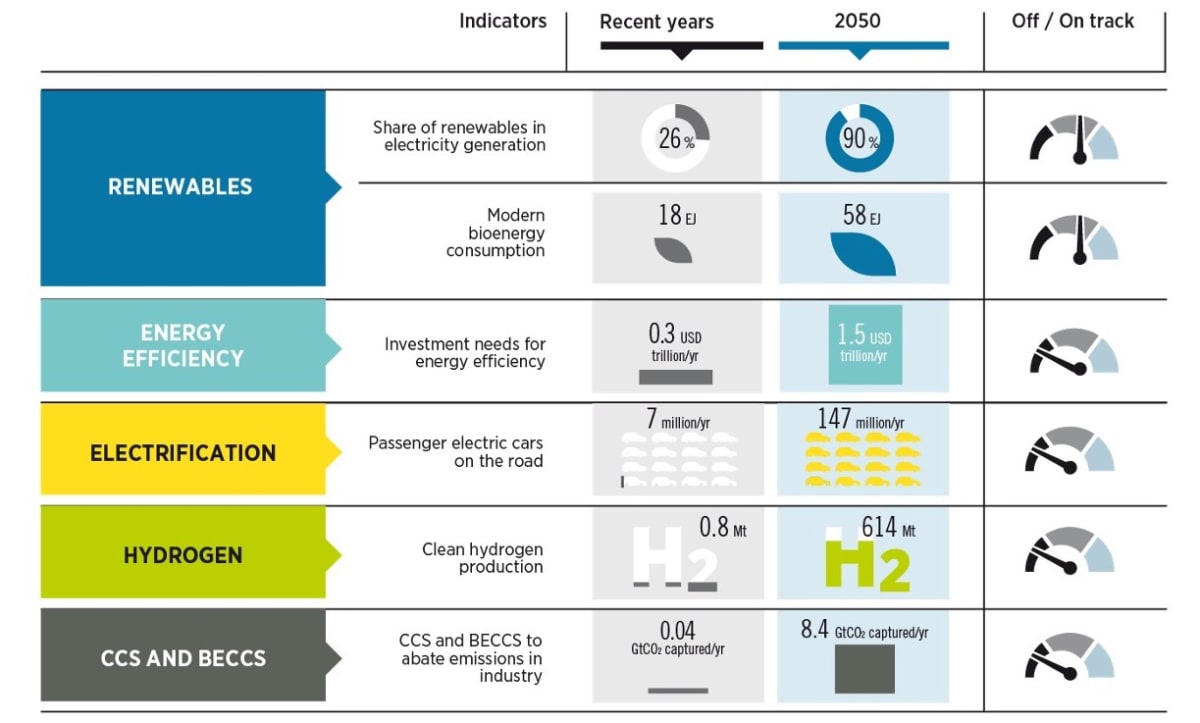

Yet, the global task ahead is still enormous and still far off track, the International Renewable Energy Agency reported this week in its annual World Energy Transitions Outlook.

It estimated that US$5.7 trillion in annual investment was needed every year until 2030 in solar, wind and other forms of clean power to ensure that global warming does not exceed “dangerous thresholds”. It also emphasised the urgent need to improve energy efficiency, increase electrification of transport and industry, capture carbon emissions and expand the use of hydrogen, among the broader measures required to limit the rise in temperatures.

However, renewables are still tracking below the pathway needed to decarbonise the global energy system by 2050, as the agency’s summary below shows.

Here in New Zealand this week, we got some very welcome news on clean energy. The NZ Superannuation Fund announced it was teaming up with Denmark’s Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners to explore the potential for large-scale wind power off the coast of Taranaki.

The strength and reliability of winds there are thought to rank well globally as a wind power source. The partners will take two years to assess the practicality of the project before deciding to invest up to $2.5 b to install 1 gigawatt of electricity capacity, equal to some 11 percent of current total NZ supply. The partners say they could potentially double that investment by 2030.

The announcement was a rare example of NZ clean energy news getting international coverage. That reflects how timidly and slowly we are transitioning to a zero emissions economy.

If war in Ukraine or pain at the pump isn’t getting you going, then read “In a world on fire, stop burning things.” This is the latest New Yorker column by Bill McKibben, the veteran global campaigner against fossil fuels. In it he very powerfully reframes the arguments and restates the evidence for the utter necessity, and achievability, of decarbonisation.

So, briefly on to the second topic – food. War and inflation are hammering supplies and prices of it, as they are oil and gas. The resulting food security debate mirrors the energy security debate. But the remedies offered are starkly different. On energy, new technologies and practices are putting up a strong fight against the incumbent ones. A much better and sustainable future is being articulated and delivered.

But there is no equivalent in farming, food and nature. Worse, some countries with strong environmental records are backsliding. Iceland, for example, facing a shortage of sunflower oil from the Ukraine, has reversed its ban on palm oil as a food ingredient, in place since 2018.

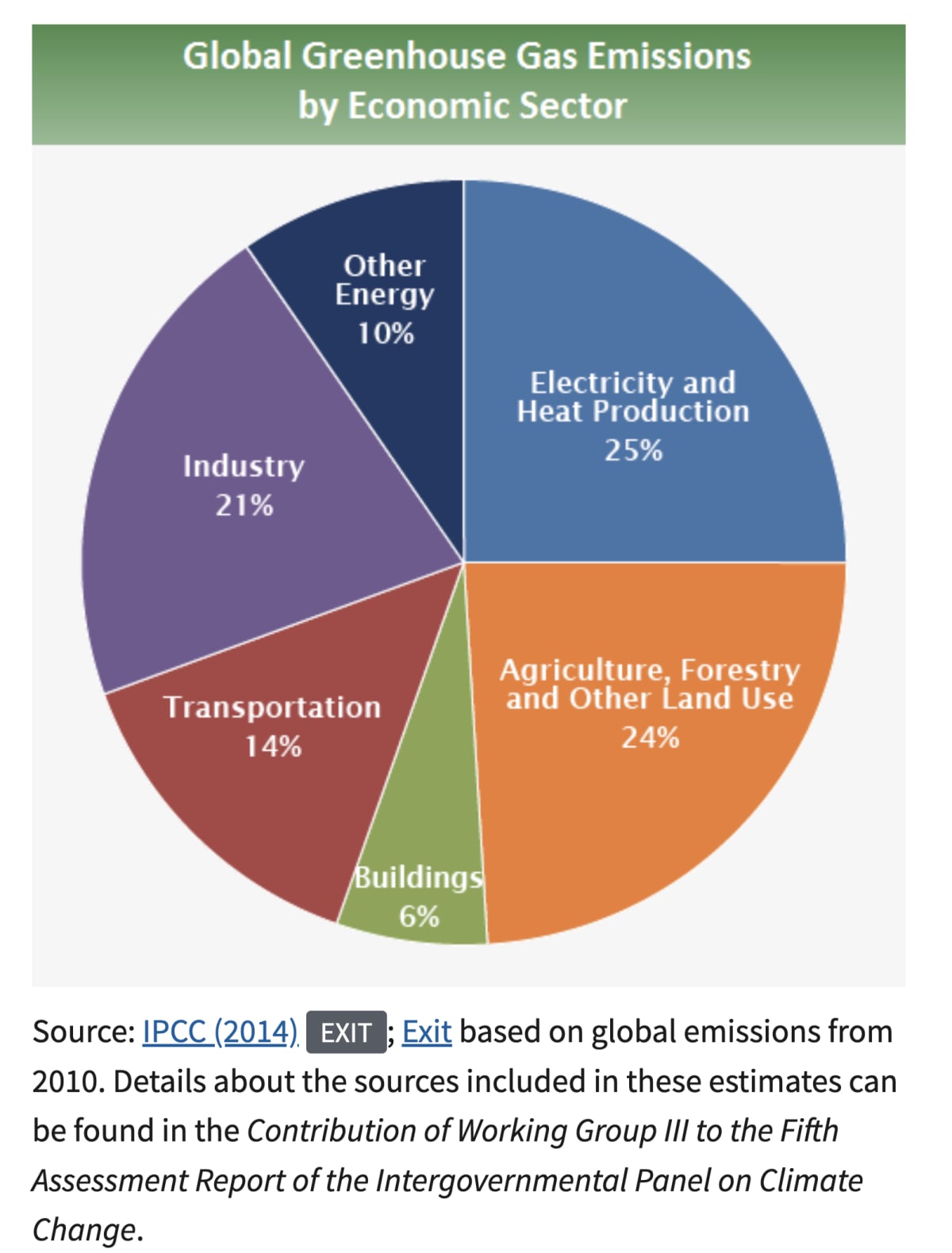

Around the world agribusiness lobbyists are arguing the only way to increase food security is to increase support for intensive farming and to scale back ambitions to develop natural carbon sinks and rewild some areas. But that's precisely the industrial agribusiness strategy that's made farming and food production a bigger source of emissions globally than electricity generation or transport, as this chart from the US Environmental Protection Agency.

The UK government is one which has responded quickly to the call. This week it delayed restrictions on artificial fertilisers which contribute to the climate crisis and, when overused, can degrade ecosystems. It also delayed longer term plans for more organic fertilisers and sustainable farming practices.

And here, our government is giving up on trying to get farming organisations to devise an on-farm emissions measurement, management and pricing framework, as Politik reported.

Instead it will include them (extremely lightly) in the Emissions Trading Scheme. But that will give them minimum incentive to reduce their emissions, which account for half our national emissions.

If our farmers fail to reduce their emissions, while others do abroad, then we'll fail as a nation to meet the climate commitments we've made to the world. Instead, we'll spend lots of money paying for emission reductions in other countries, leaving our old agtech economy pumping out climate and nature-damaging emissions.

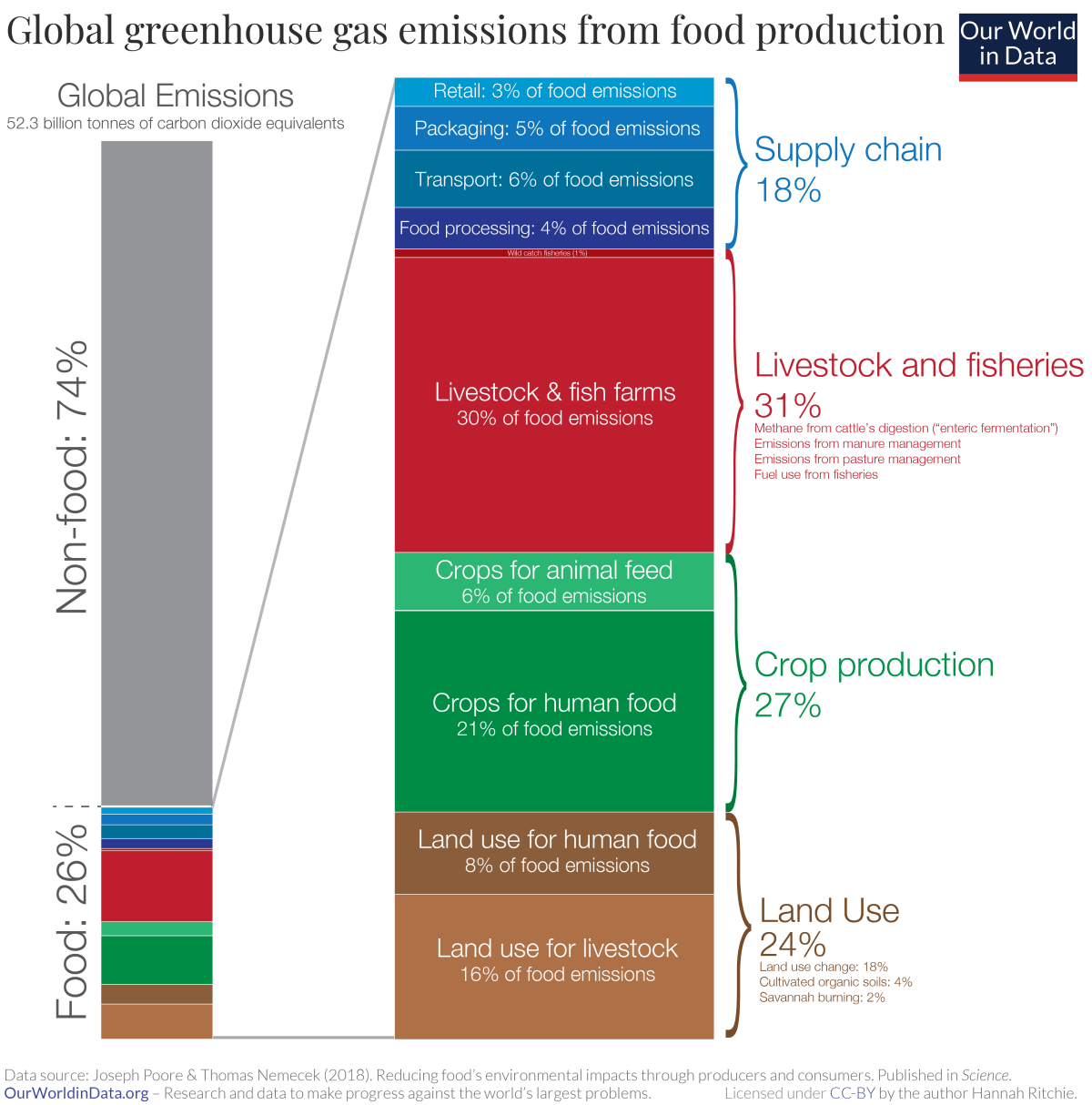

Where, around the world and here, are the well evidenced and argued calls for eating less meat (given its large farming and greenhouse gas footprint) or switching some land back to growing food for people, rather than as a fuel source or feed for animals? In the US for example, 27 percent of corn is used to make ethanol fuel and 39 percent as animal feed, as the World Economic Forum reported last year.

Meanwhile, there was discouraging news from the UN’s efforts to tackle nature’s deeply systemic issues of biodiversity loss, land degradation and ecosystem impairment. The first in-person negotiations in two years on a treaty to tackle those went badly in Geneva. After 18-days of talks there was far too little progress towards the COP15 biodiversity summit later this year in Kunming, China.

The UN is trying to bring its biodiversity and climate streams closer together, given their deep symbiosis. Thus, big biodiversity progress at COP15 in China would help countries achieve more at COP27, the climate negotiations in Egypt in November.

Cleaning up energy and food, and thereby restoring nature are just three of our urgent tasks. But if we achieve them quickly, we will open up many other areas of human progress.