“Do Black comedians have a right to offend? No, we have a JOB to offend.” — Alonzo Bodden

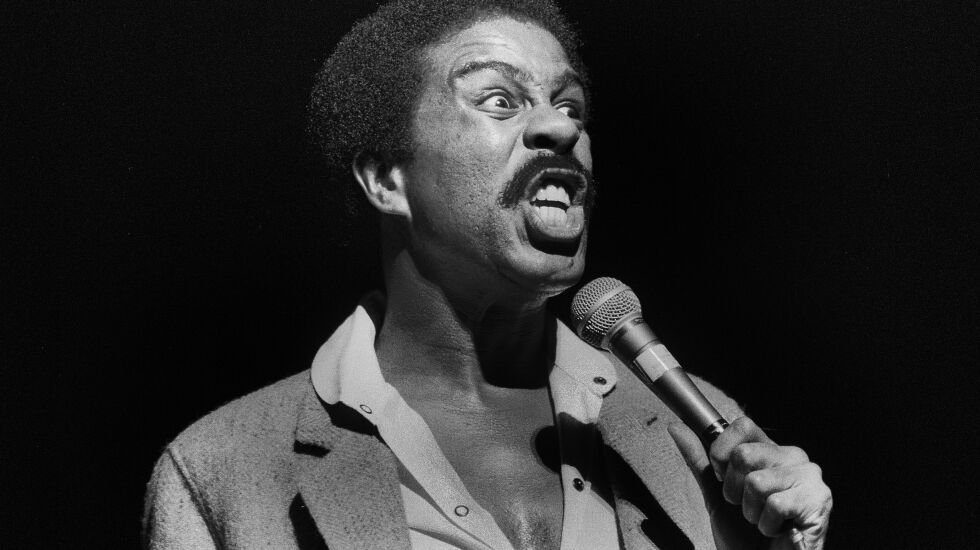

A prominent Black comedian is talking about police shootings of young Black men: “How do you accidentally shoot a n------ six times in the chest? ‘Well, my gun fell and just went crazy.’ ”

That could be Dave Chappelle or Chris Rock or any of other dozen modern-day comedic greats on stage in 2022 — but the comedian was Richard Pryor, and the observation was made a half-century ago, and the clip is from the two-part A&E documentary series, “Right to Offend: The Black Comedy Revolution.”

From executive producer Kevin Hart and co-directors Mario Díaz and Jessica Sherif, this is a timely, insightful, comprehensive, historically valuable chronicle of the Black comedy experience in America, from the minstrel acts of the early 20th century through the emergence of pioneers such as Redd Foxx and Dick Gregory and Slappy White in the 1950s and early 1960s to the revolutionary comedy of Richard Pryor in the 1970s to the rock-star ascension of Eddie Murphy in the 1980s through breakthrough TV shows such as “In Living Color” and “Def Comedy Jam” in the 1990s to present-day creative forces such as Issa Rae and Amanda Seales and Michael Che and Donald Glover, to name just a few.

This two-part series is a master class in Black comedy, but it never feels like a lecture because it’s also friggin’ FUNNY, as we’re treated to a bounty of brilliant archival footage from one Hall of Fame level comedian after another, whether it’s stand-up routines or talk-show guest shots or audio snippets from classic comedy albums. Yes of course, these trailblazing comics were commenting on race relations, oppression, poverty, violence, incendiary politics and other hot-button issues — but they made their points in flat-out hilarious fashion, with observational monologues and rapid-fire jokes that yielded huge laughs. Funny is funny is funny is funny.

Co-directors Díaz and Sherif wisely let the material — and the greats — do the talking, eschewing any unnecessary flourishes or timeline hopping in favor of a mostly linear, straightforward approach to the material. We occasionally see news footage of relevant and revolutionary moments in American history, from the protests of the 1960s to the Black Lives Matter movement of the 2010s, providing context to the aforementioned archival footage, which is augmented by insightful interviews with academics and historians such as Todd Boyd, Michael Eric Dyson, Mark Anthony Neal, Elizabeth Stordeur Pryor (Richard’s daughter) and Bambi Haggins.

And we get frank and often laugh-inducing insights from generations of comedians, including Michael Che, Tiffany Haddish, Steve Harvey, Sherri Shepherd, Chris Rock, Tommy Davidson, Jimmie Walker. D.L. Hughley, Aisha Tyler, Kenan Thompson, Amber Ruffin and Amanda Seales. (My only complaint would be that we’re left wanting to hear even more from the interview subjects.)

“Your role is bigger than being funny,” says Hart, a sentiment echoed time and again by modern-day comics, as when Amanda Seales notes, “Out of crisis comes comedy.”

In “Part 1: The Revolutionaries,” we get a brief history of Black comedy in the early 20th century — I was today years old when I learned Charlie Case finished off his jokes with a punching gesture, hence the phrase, “punchline” — before we’re reminded of how Dick Gregory was a massive crossover star who put his career on the back burner to be on the forefront of the civil rights movement. We also hear about the underground “party records” phenomenon, with Black comics doing not-safe-for-broadcast material on albums that would be played during parties. (Redd Foxx did more than fifty such albums.) Richard Pryor is of course a huge figure in the series, with Paul Mooney getting his due as a force of his own and a mentor-writer for Pryor.

There are some interesting detours into the world of sitcoms, as when we see how “Good Times” stars John Amos and Esther Rolle were concerned about Jimmie Walker’s “DYN-O-MITE!” hamming it up, as they felt it distracted from the show’s larger goal of portraying a Black family in the Chicago housing projects in an authentic manner.In Part 2, titled “The Contemporaries,” we’re reminded of how there was criticism of Eddie Murphy for not being more political, but it’s pointed out that Murphy DID include social commentary in his comedy routines and on “SNL,” and his rise to global superstardom was in and of itself pioneering. Black comedy clubs such as the Comedy Act Theatre in South Central L.A. and the Uptown Comedy Club in Harlem are recognized, followed by sections on Chris Rock and Dave Chappelle bringing social criticism back to the stage.

The latter sections of the series focus on the last 10 years, with the election of Donald Trump, the murder of George Floyd, the chilling rise in white supremacy and other events of monumental consequence giving rise to a whole new level of political and social commentary. (Naomi Ekperigin, onstage: “Nazis are out! They’re out without hoods, getting haircuts!”) It’s all terribly sobering and yet grounds for fertile comedy, and we’re left remembering what Dick Gregory said more than a half-century ago: “If we don’t make massive changes, this country is doomed.”