Bright and steadfast, quasars help astronomers in many ways. They are the glowing rubbish that supermassive black holes collect and cast off into space from the center of galaxies. Researchers use these distant luminosities as a constant when measuring the motions of objects closer to home, but quasars are also fascinating by their very nature. In a few months, they will be among the first objects NASA’s latest space telescope will study.

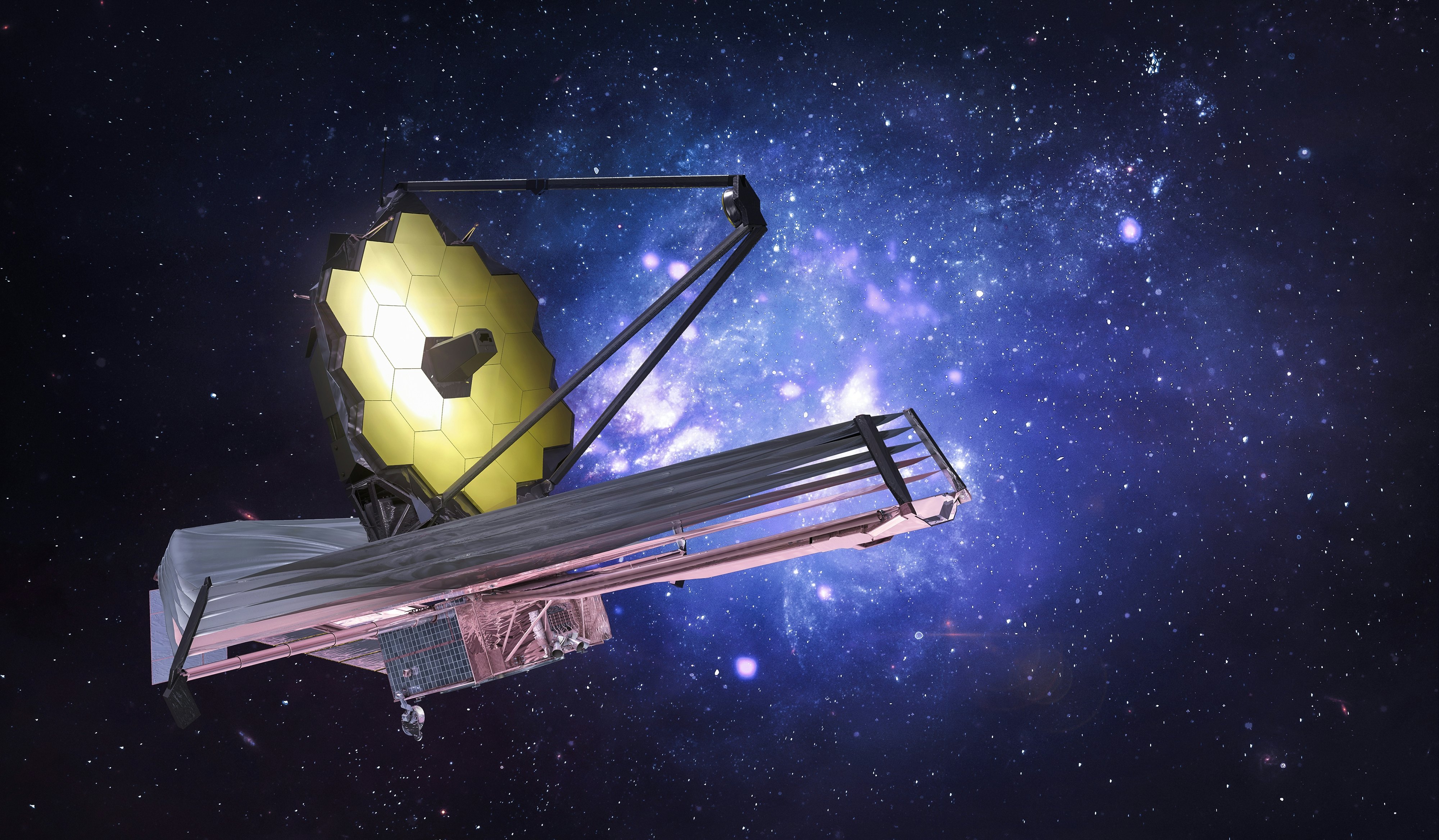

Astrophysicist Dominika Wylezalek is studying quasars to learn about the evolution of the universe. She is leading a science team called “Q3D,” which will study three quasars sitting at different distances from Earth. The team will be among the lucky few to preview the unique light-viewing capabilities of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) launched this observatory from South America at the end of 2021, and after months of alignment, the telescope is now weeks away from premiering its first pictures. Beyond their beauty, the images that Webb captures can also reveal information about key cosmic phenomena.

“JWST opens up an entire new window here, with the ability to investigate distant galaxies in the early Universe in the same way as nearby galaxies,” Wylezalek tells Inverse.

Why it matters — Quasars may be fundamental to limiting the size of hefty galaxies larger than the Milky Way.

They are a by-product of supermassive black holes, the gargantuan objects living at the heart of most, if not all, galaxies in the universe.

Although astronomers harness quasars’ distant brightness to render a still cosmic background by which to track the motions of nearby stars or to follow Earth’s wobbles, their staunch radiance can mask what is happening near them.

Astronomers hope that Webb will make it easier to see the faint galaxies that host quasars, revealing the key role that quasars might play in their formation.

“Scientists think this quasar–galaxy connection is crucial in determining how galaxies evolve from the early universe to today,” according to NASA representatives describing Wylezalek’s work.

What’s new — Q3D will pair Webb’s observations with new software to peer beyond the quasars’ brightness to view the faint stuff that their intensity obscures.

Observational evidence is hard to obtain, but scientists have hypothesized for decades that quasars limit galactic gains. The idea so far is that quasars flush out hundreds of solar masses of material each year, leaving the galaxy with less stuff with which to create new stars. The three quasars could help astronomers understand the mechanisms at play in more distant quasars.

What’s next — Wylezalek’s team is in the enviable position to pursue their curiosity while testing out a brand new space telescope.

“Our team is very excited for this data to come in,” Wylezalek tells Inverse.

Q3D will participate in the first five months of Webb’s work, known as the Director’s Discretionary Early Release Science (DD-ERS) program.

“We hope that the data will indeed shed new light on some of the mechanisms at play in distant galaxies, with regards to how supermassive black holes and their host galaxies interact with each other,” Wylezalek says.