“In his time, in his time. He makes all things beautiful in his time.”

As he sang, his 69-year-old wife Julita Bartolome, who in 2019 was deported to her native Philippines after more than 30 years in the United States, emerged from a door behind the pulpit. She was to join him in a duet of the song, but the plan was derailed when members of the congregation began to cry and rush the pulpit to hug her.

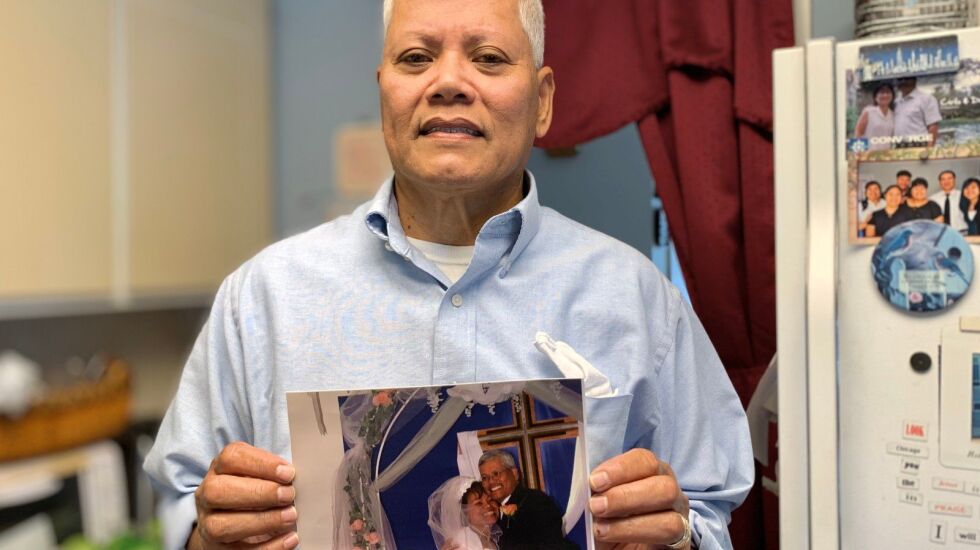

Aaron Bartolome was at a different church that morning but later saw a video recording and said: “It was a nice reunion for the people at the church. They really missed her.”

In 2019, WBEZ first reported that Julita Bartolome was deported during a wave of immigration crackdowns by the Trump administration.

More than three years later, she’s back home in Mount Prospect — for good this time, according to Katherine Del Rosario, the family’s lawyer.

“I feel like we’ve lived many lifetimes since that summer in 2019,” Del Rosario said. “I think they’re just eager to kind of pick up where they left off — to keep doing what they did before and serving the families at their church together.”

Del Rosario said the case was slowed by the COVID-19 pandemic and a typhoon in the Philippines that delayed the delivery of her immigrant visa to her mother’s home.

After news of Julita Bartolome ’s deportation drew international attention, a GoFundMe set up by a friend raised more than $15,000 for Edgardo Bartolome to visit her that Christmas and cover some legal costs.

Then, the pandemic set in.

Del Rosario said the Bartolomes had to file a waiver to forgive Julita Bartolome’s initial overstay and then apply for admission in the United States after deportation, demonstrating medical and financial hardships her husband faced as a result of the deportation. Del Rosario said what might have been a wait of a year and a half stretched into three years because of the immigration backlog the pandemic created.

“What the pandemic did is highlight just how understaffed and underfunded Immigration Services and the consulates are with many essential services,” Del Rosario said.

Aaron Bartolome, Julita Bartolome’s stepson, said she had been staying at her mother’s house in the Philippines and, at one point during the pandemic, everyone in the home had COVID. He said vaccines in that part of the country weren’t readily available, and many people in the province were dying.

This past summer, the family finally got word the waivers they needed to get the immigrant visa had been approved. Still, Aaron Bartolome said, they were afraid to get their hopes up until the visa arrived two weeks ago.

“That’s when we’re, like, ‘It’s real,’ ” he said.

Del Rosario said U.S. Rep. Jan Schakowsky, D-Ill., and her staff were instrumental in securing Bartolome’s return, pushing to expedite the case.

“The story of the Bartolome family is one that I will never forget,” Schakowsky said in a written statement, saying she was devastated by the deportation and that she and her staff “made it our mission to reunite Edgardo and [Julita].

“There is no better feeling than being able to reunite a family,” she said.

Aaron Bartolome said that, when he saw his stepmom, “We hugged each other for a really long time.”

He said he had been busy with work and that he and his father had been eating a lot of takeout recently.

“My dad and I were laughing because now we have groceries at home,” he said — including Aaron Bartolome’s favorite snacks, which Julita Bartolome bought at the Chicago supermarket Seafood City.

He said his parents and extended family were shellshocked by the news media attention following her deportation and did not want to be interviewed about the reunion.

But Aaron Bartolome said he wanted to share his family’s story because it could help “other families that are hurting.”

He said his stepmother’s detention was “heartless, insensitive, no compassion at all,” recalling how, in the first days, he and his father didn’t know where Julita Bartolome was being held.

Del Rosario said the deportation was “very important for me as an attorney, as a Filipino American person, as someone’s daughter.”

Del Rosario — who continues to provide legal help to low-income immigrants and refugees through the Alliance for Immigrant Neighbors, a nonprofit clinic she cofounded during law school — said the Bartolomes’ story led other Filipino immigrants to contact her.

“Seeing a Filipino family go through this was really compelling for people who might not otherwise pay attention to immigration issues that usually have different faces and stories associated with them,” she said.