Neolithic Britons cooked cereals, including wheat, in pots to make early forms of gruel and stew, new research has suggested.

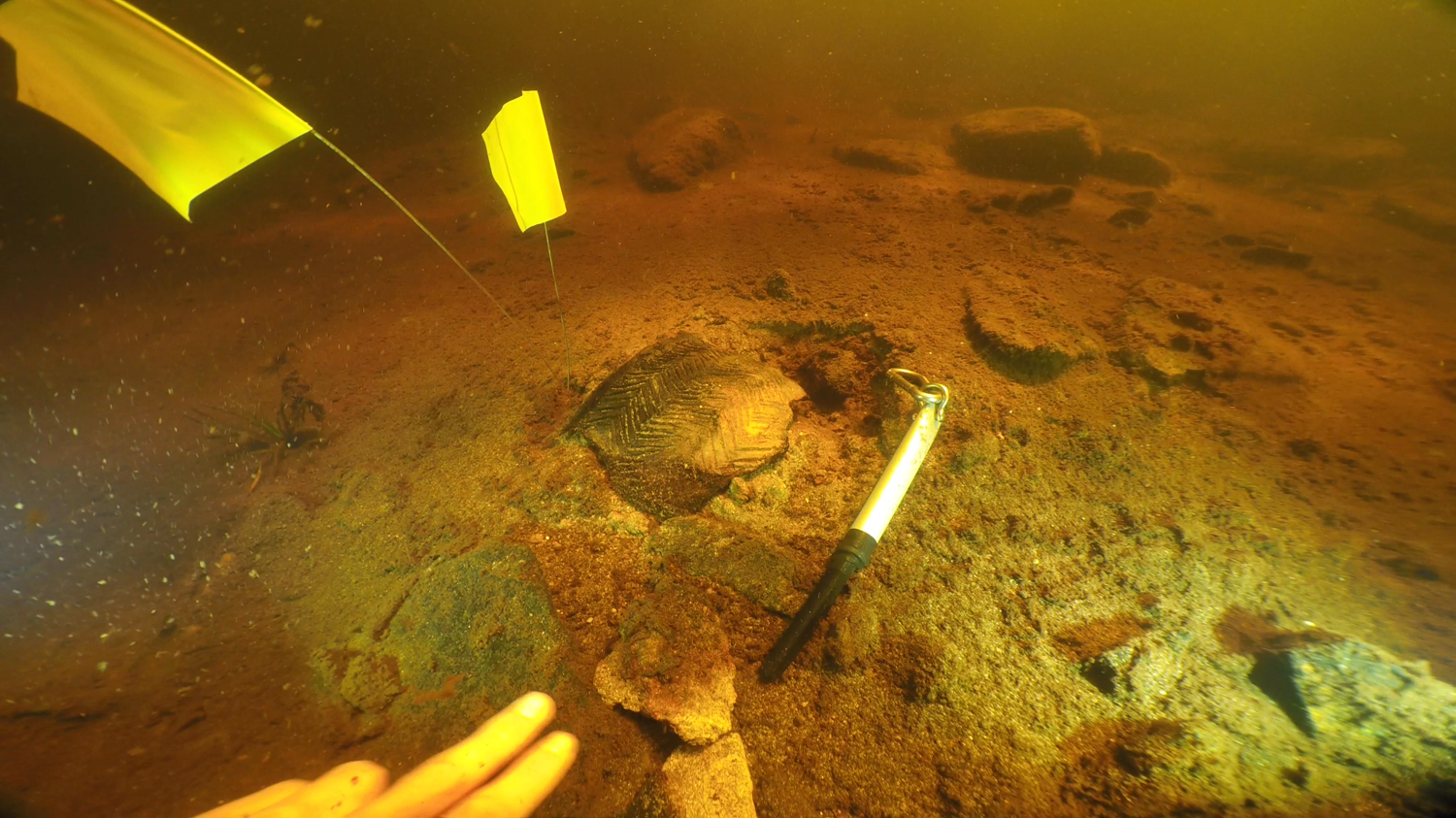

Scientists made the discovery by carrying out chemical analysis of ancient and incredibly well-preserved pottery found in the waters surrounding small artificial islands called crannogs in Scotland.

The team, led by University of Bristol scientists, discovered cereals were cooked in pots and mixed with dairy products and occasionally meat, probably to create early forms of gruel and stew.

They also discovered the people visiting these crannogs used smaller pots to cook cereals with milk, and larger pots for meat-based dishes.

Crannog sites in the Outer Hebrides are currently the focus of the four-year Arts and Humanities Research Council-funded Islands of Stone project.

Dr Lucy Cramp, of the University of Bristol’s Department of Anthropology and Archaeology, said: “This research gives us a window into the culinary traditions of early farmers living at the north-western edge of Europe, whose lifeways are little understood.

“It gives us the first glimpse of the sorts of practices that were associated with these enigmatic islet locations.”

Researchers said their approach has now revealed evidence for cereals in Neolithic pottery from Scottish crannogs dating to around 3600 to 3300 BC.

Cereal cultivation in Britain dates back to around 4000 BC and was probably introduced by migrant farmers from continental Europe.

The Neolithic period lasted from around 4000 to 2500 BC in Scotland.

Pottery was also introduced into Britain at this time and there is widespread evidence for domesticated products like milk products in molecular lipid fingerprints extracted from the fabric of these pots.

Previously published analysis of Roman pottery from Vindolanda (Hadrian’s Wall) demonstrated that specific lipid markers for cereals can survive absorbed in archaeological pottery preserved in waterlogged conditions and be detectable through a high-sensitivity approach.

However, this was only 2,000 years old and from contexts where cereals were well-known to have been present.

The new findings show that cereal biomarkers can be preserved for thousands of years longer under favourable conditions.

Researchers also found that many of the pots analysed were intact and decorated, which could suggest they may have had some sort of ceremonial purpose.

Dr Simon Hammann, previously of the University of Bristol, said: “It’s very exciting to see that cereal biomarkers in pots can actually survive under favourable conditions in samples from the time when cereals (and pottery) were introduced in Britain.

“Our lipid-based molecular method can complement archaeobotanical methods to investigate the introduction and spread of cereal agriculture.”

Dr Hammann is now based at the Friedrich-Alexander-Universitat Erlangen-Nurnberg in Erlangen, Germany.

The research is published in the journal Nature Communications.