Conversations around obesity tend to focus on how this condition is associated with heart disease, metabolic disorders such as diabetes, or respiratory issues like sleep apnea. But increasingly, researchers are finding more connections: Obesity may also be affecting our brains. Studies have found that the condition can damage memory, attention, and other executive functions by weakening underlying structures of the brain. To that end, obesity is considered a risk factor for neurodegenerative diseases like dementia and, now, potentially, Alzheimer’s disease.

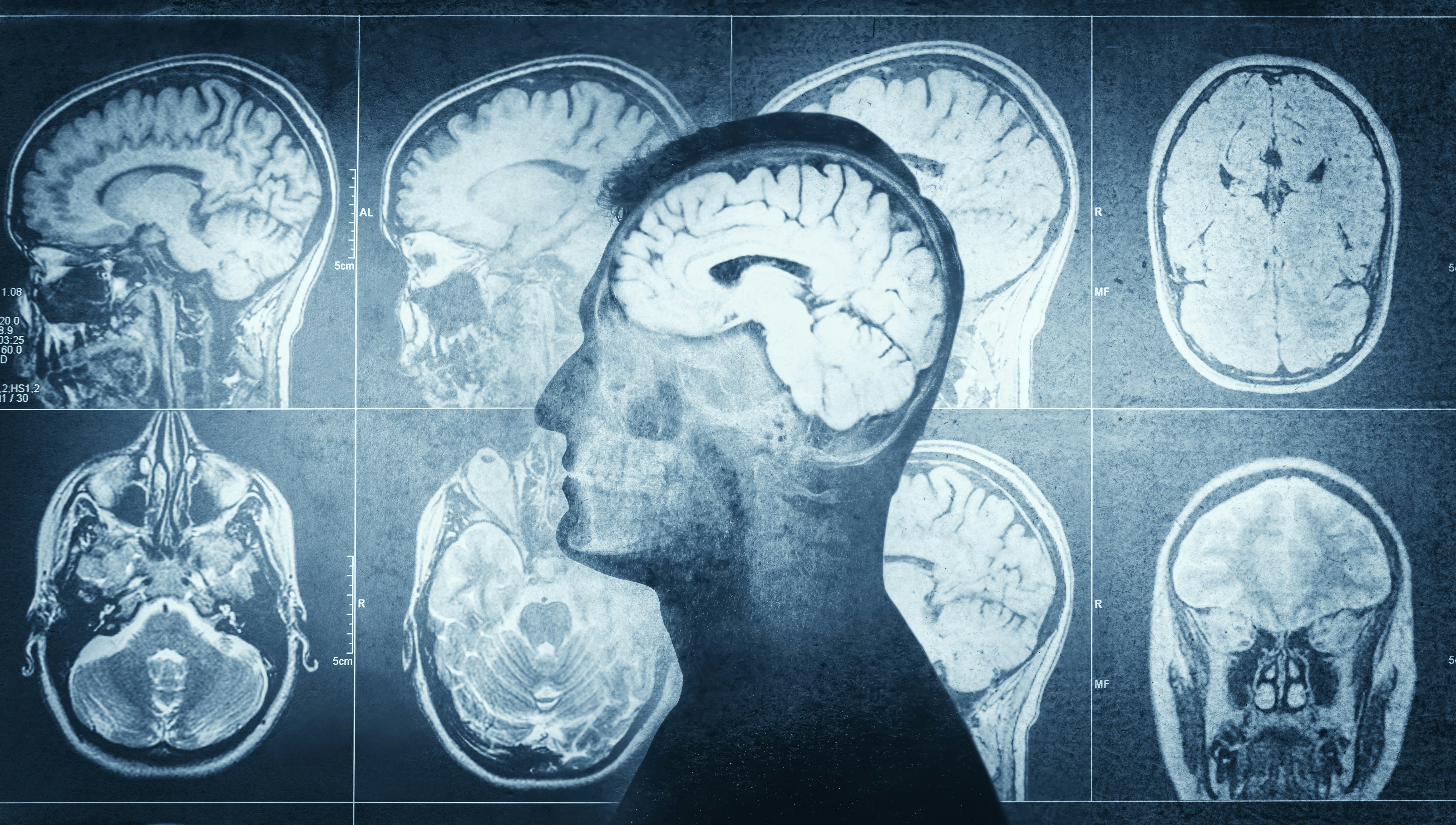

In a study published this month in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, a group of Canadian researchers compared brain imaging between obese people and people with Alzheimer’s disease. They found both groups shared similar patterns in brain volume loss, particularly gray matter, which are regions throughout the brain where neurons are concentrated.

“The finding is very striking in that there’s this correspondence between the atrophy pattern of obesity with Alzheimer’s disease,” Carolyn Fredericks, an assistant professor of neurology at the Yale School of Medicine who was not involved in the study, tells Inverse. It adds to the growing body of evidence “that [conditions] associated with obesity, like diabetes and heart disease, can cause similar kinds of processes in the brain and contribute to Alzheimer’s disease.”

How they did it – In previous work, Filip Morys, a neuroscientist at McGill University’s Montreal Neurological Institute who led the new study, found that measures of obesity like body mass index (BMI), waist-to-hip ratio, and body fat percentage were associated with hypertension and diabetes. These conditions, in turn, appeared to feed into cerebrovascular diseases that affect blood vessels and blood flow to the brain and, by association, impaired cognition.

“We saw that brain patterns we find in people with obesity [were] very similar to ones that we see in Alzheimer’s disease,” Morys tells Inverse. “ So we wanted to directly compare that and see if what we [saw] is actually statistically true as well.”

To do that, the researchers tapped into the UK Biobank, a large-scale database containing biomedical information on a half million British individuals, and the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) launched in 2003. From both, Morys and his colleagues took brain images called structural MRIs (which provide information on the shape, size, and integrity of the brain and its structures) from a sample of over 1,300 individuals. These were used to create brain maps to identify the location of structural brain changes. For the obesity brain maps, MRIs of obese people were assembled by comparing them against brain scans of lean individuals (both sourced from the UK Biobank). For the Alzheimer’s disease brain maps, the researchers used a similar approach but compared MRIs of afflicted patients against a neurologically healthy control group (both from ADNI). Whether an individual was obese was largely determined by a BMI of over 30 kilograms per meter squared (BMI is a measurement fraught with its own controversy).

What they found – Looking at the two brain maps side-by-side, Morys and his team saw that obesity and Alzheimer’s disease shared similarities in how thin the gray matter of the cerebral cortex was. The cerebral cortex is the outermost layer of the brain associated with higher-level brain functions we use to coordinate cognitive abilities and behaviors like memory, thought, language, and more.

“We found those correlations mostly in the frontal and temporal brain regions, which are very much changed in Alzheimer’s disease,” says Morys. “The frontal temporal regions [and] frontal temporal junction sort of takes part in memory, which is why in Alzheimer’s disease, the first manifestation is memory loss and cognitive impairment.”

Why it matters – While first described more than a century ago, Alzheimer’s disease is still poorly understood. Notably, scientists still don’t fully understand what increases an individual’s risk for the condition. However, we do know part of one’s risk is tied to genetics, Riddhi Patira, a neurologist and investigator at the University of Pittsburgh’s Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center who was not involved in the study, tells Inverse.

“In late-onset [Alzheimer’s disease], the only known risk factors are APOE4 [a protein called apolipoprotein E] and age,” Patira says, with studies showing that inheriting one or two copies of APOE4 from your parents increases your risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease at an earlier age. (About two to three percent of people carry two copies, according to the NIH.)

Studies have found external factors like your exercise habits, whether you smoke, and how healthy your diet is can all contribute to your risk. Additionally, where you live and your socioeconomic status can, too. Individuals who experience persistent low wages, and unemployment or live in a disadvantaged neighborhood with no easy access to health care are at an increased risk for cognitive decline and dementia (Alzheimer’s disease being a type of dementia.) But how all these factors work together is far murkier, says Patira. It’s hard to say whether modifying one’s lifestyle or environment alone can help improve someone’s Alzheimer’s symptoms or entirely stave off the disease.

Additionally, the study doesn’t directly connect obesity with Alzheimer’s disease, which is an important distinction.

“We already know that things like mid-life and activity and diabetes, both of which are associated with obesity, are risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease,” says Fredericks. “It’s tough because is being obese itself a really big risk factor? Or is it just that if you’re obese, you’re probably more likely to have diabetes? I think we have to be careful about inferring that obesity is a problem when really it might be something associated with obesity. [It also] may not be true of all people with a BMI above a certain cutoff.”

Morys proposes that what might be linking obesity to Alzheimer’s disease is inflammation. For example, in some studies where mice are fed a high-fat diet and gained weight, inflammation appeared to promote the toxic build-up of proteins called amyloid-beta and tau that are associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

“Inflammation is, [maybe] one part for sure, related to brain atrophy. There are other mechanisms related to a lot of comorbidities like type two diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, all of those increase oxidative stress on the brain,” says Morys. “Obesity is also related to leptin [a hormone that regulates appetite] and insulin resistance, both of them are neuroprotective, but you kind of lose that neuroprotective factor [with obesity].”

What’s next – Since this is only a correlation study (it can’t really tell us anything about causation) and it's cross-sectional (it can only tell us about one point in time, not how obesity affects an individual’s brain over a period of time), Morys says further research sussing the relationship between obesity and Alzheimer’s disease is needed, particularly seeing if a healthy weight can help with treating or offsetting Alzheimer’s disease.

“[We’re] focusing right now on the weight loss part, that’s really exciting to me. I’ve always wanted to do more clinically applicable studies,” he says. “I think if we’re able to show weight loss [protects] the brain, that would be amazing.”

Patira and Fredericks don’t feel this study radically transforms how Alzheimer’s disease patients are currently treated in the clinic — except to further cement the relationship between neurodegeneration and obesity. It may open up avenues for new Alzheimer’s drug treatments, although it’s too early to tell, says Patira. But considering that nearly half of all U.S. adults will be obese by 2030 and the number of people living with Alzheimer’s disease is expected to double to 13 million by 2050, the convergence of those populations may tax our already taxed health care systems.

“It’s something that our public health system is not going to be able to support,” says Fredericks. “I think if anything, the importance of a healthy lifestyle… getting consistent cardiovascular exercise and changing your diet to more of a Mediterranean or DASH [Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension] diet [and] that, regardless of your BMI, is going to set you up for a healthy, older adulthood.”