How much is a human life worth?

The answer is $5.3 million if you ask the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, which has tried to measure the price society is willing to pay to reduce the risk of death.

In reality, it is the sort of question only a bureaucrat would ever attempt to answer.

The reason is it is impossible to say, given life is in fact of immeasurable value and one person could, in the eyes of some, be worth all the money in the world.

For many years, grieving families have accused the ACT Coroner's Court of not placing enough value on the lives of their loved ones.

Those left behind speak of having to pay an emotional price that is too high.

Eminent lawyer Bernard Collaery agrees, saying the territory has been home to "a lamentable scene" in the coronial space.

The former ACT attorney-general recalls families waiting as long as seven years for inquests, describing the difference between this and the urgent response seen in homicide investigations as "night and day".

The system has been changing for the better in recent times, with experienced local barrister Ken Archer appointed as the ACT's first dedicated coroner.

Since taking up the role last year, Mr Archer has set about addressing a backlog of cases and changing the way the court interacts with grieving families.

His appointment came about, in no small part, due to the advocacy of mothers determined to see the system improved following inquests into the deaths of their children.

While some of those advocates acknowledge the good work done so far, they, like Mr Archer and others experienced in the coronial space, want the ACT government to understand the job is far from over.

"We've got there in some ways, but there's so much more to do," one fierce advocate for reform, Ann Finlay, says.

Families 'extras in a play'

It took nearly a decade for the coronial recommendations that flowed from the 2010 prescription medication overdose death of Ms Finlay's son, Paul Fennessy, to be implemented.

"I suppose for me, the thing is how many deaths could have been prevented in those nine years if they had real-time [prescription] monitoring?" Ms Finlay wonders.

The delay is a frustration shared by many of the families forced to endure coronial inquests in the ACT, but the process itself has been one of the biggest issues.

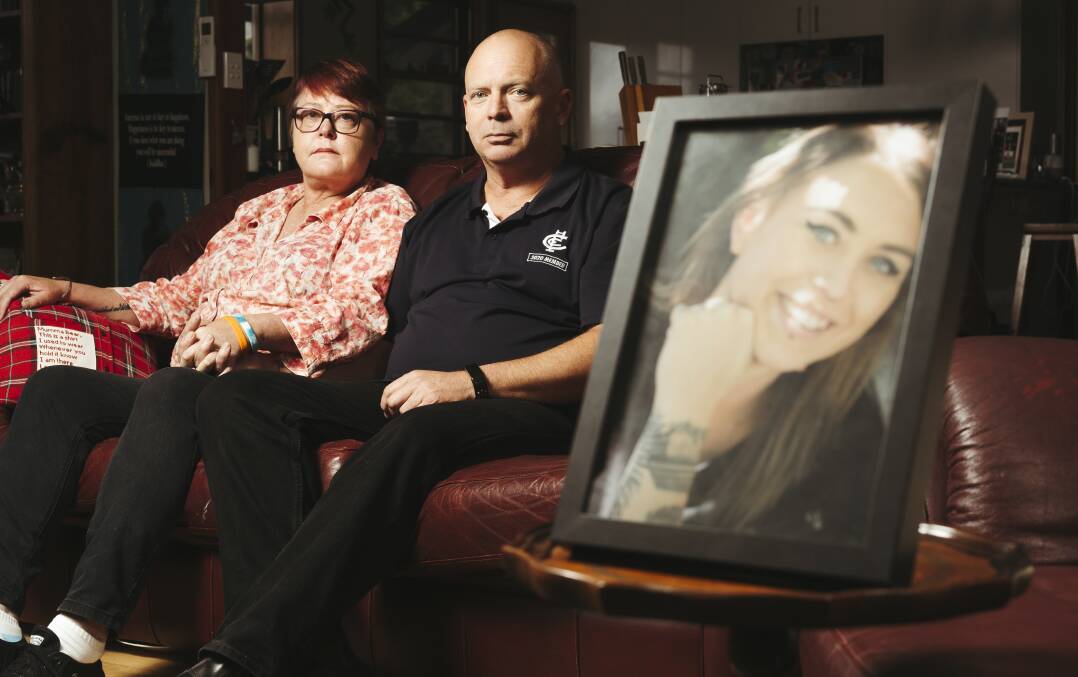

"Sometimes, as a family, you just feel like extras in a play," another coronial reform advocate, Janine Haskins, tells The Canberra Times.

Ms Haskins, who lost beloved daughter Bronte Haskins in 2020, describes the process as "quite punitive" for families, lamenting the often adversarial nature of coronial inquests.

"I felt like I was a defendant in Bronte's hearing," she says.

Both women want to see reforms that would require legislative change, including the replacement of coronial recommendations with directions the ACT government must follow.

Other suggestions put forward by Ms Haskins would cost nothing.

She is talking about the simple addition of kindness to coronial proceedings, and a shift to using names in inquests instead of the dehumanising description of "the deceased".

Advocates are also keen to see the dedicated coroner given the statutory recognition he has called for, and for money to be allocated to fund more family liaison officers for the court.

"They can always find [money] for other things," Ms Haskins says, recalling a time she read about millions of dollars being spent to furnish a government building.

"Families need to be furnished with assistance too."

'We're going to need more people'

Mr Archer is not a man who needs convincing of the court's past shortcomings.

He knows about the trauma the system has inflicted on the likes of Ms Finlay and Ms Haskins, and is determined that others will not experience the same "disastrous" things.

"It's bad news city," Mr Archer says of the coronial realm.

"It's about death and it's about grief. And going through a formal court process, inherently, so far as an emotional impact is concerned, has the potential to heal but also has the potential to harm."

One of the important things he has already done is open up communication with grieving families in order to learn what they would like to get out of the coronial process.

As the ACT government recently announced, the Coroner's Court will receive funding for a second family liaison officer and a specialist forensic counselling service.

These are encouraging developments for the dedicated coroner, but he knows these measures are not magic wands.

"Even with the assistance that's coming out of the recent budget round, the reality is we're going to need more people to speak to families," Mr Archer says.

"I think, as a general proposition, we need to increase particularly our investigatory sorts of numbers.

"Because the big problem has been delay.

"And it's not about getting judgments out of me. It's about getting cases investigated.

"It's not a chiefs issue. It's an Indians issue, just getting people on the ground."

Mr Archer has already set about addressing delay by declaring that matters with a public profile, like the Canberra Hospital death of five-year-old Rozalia Spadafora, will be heard within a year.

"I think unless there's an immediacy, a result, in those sorts of cases, you lose the opportunity to effect meaningful change," Mr Archer says.

This approach is a far cry from that which saw four patient suicides at Canberra Hospital examined together in an inquest that delivered recommendations some six years after the first death.

A misunderstood purpose

Any mention of the coronial system inevitably conjures unwelcome images of death.

It is therefore unsurprising that many people do not even want to think about it, much less understand it.

The result is that many write it off without realising death is only the start of what the coronial system is about.

In fact, as Mr Collaery points out, its most important priority is the very opposite of death.

"You're talking about inquiring into the loss of life so you can save lives," Mr Collaery says.

This is something the Canberra families heavily involved in the ongoing fight for coronial reform understand.

They know they cannot bring back their loved ones, but, selflessly and graciously, they want to prevent others having to walk in their shoes.

Former NSW deputy state coroner Hugh Dillon is an admirer of the work done by the likes of Ms Haskins and Ms Finlay, the latter of whom set the agenda for coronial reform when she joined forces with the late Ros Williams and Eunice Jolliffe.

"This is almost unique, this group of people," Mr Dillon says.

He reflects on the fact most people involved in coronial proceedings feel "crushed" and in no frame of mind to "stand up to the system".

"This is one of the most bewildering, confusing and shattering experiences a person can go through," he says.

'You can save millions'

According to Mr Dillon, who is currently comparing coronial systems of the world as part of a PhD, the gold standard can be found in Victoria.

That state's system is based on two pillars, which are looking after families and preventing future deaths.

In relation to the latter, Mr Dillon refers to the study that places the value of a human life at $5.3 million.

That figure dwarfs the $3.4 million the ACT government set aside to fund Mr Archer and support staff for the dedicated coroner over a four-year period.

"[If] you save a life or two, you've more than paid for a coronial system," Mr Dillon tells The Canberra Times.

"You can save millions if the coronial system does its job."

For its part, the ACT government says it will consider additional funding needs "in the context of future budget processes".

A spokesperson for its Justice and Community Safety Directorate also indicates there are no plans to change the status quo, in which Mr Archer is, as he puts it, "a magistrate doing coronial work".

"The ACT government has made a significant investment in the Coroner's Court," the spokesperson says.

Mr Archer considers it important that the dedicated coroner role be given statutory recognition and so do advocates like Ms Finlay and Ms Haskins, the latter of whom refers to the system's potential to save lives.

"The bureaucrats need to sit up and listen, and be accountable for why there aren't resources," she says.

"Let's not bloody wait for another death."

- Support is available for those who may be distressed. Phone Lifeline on 13 11 14; MensLine on 1300 789 978; Kids Helpline on 1800 551 800; beyondblue on 1300 224 636; 1800-RESPECT on 1800 737 732.