The U.S. State Department removed Cuba from its list of countries “not fully cooperating” with anti-terrorism efforts in mid-May 2024, but you would be forgiven for not noticing.

There was little fanfare accompanying the news: no press release, and no public acknowledgment from President Joe Biden.

Rather, the decision was relayed via a department spokesperson who rather dryly explained that, “the circumstances for Cuba’s certification as a ‘not fully cooperating country’ have changed from 2022 to 2023.”

Despite the low-key nature of the announcement, taking Cuba off the list is a big deal. As an expert in counterterrorism and a former State Department official who directed the government’s counterterrorism sanction initiatives, I see the latest move as a potential step toward a rapprochement between Washington and Havana.

Delisting Cuba

With Cuba’s removal, only North Korea, Iran, Syria and Venezuela remain on the list, which was adopted in the 1990s. While being named a “not fully cooperating country” has few legal consequences, it gives pause to people, companies and countries that otherwise might be looking to do business with those states.

In some ways, the State Department announcement on dropping Cuba from the list is lagging behind actual practice.

U.S.-Cuba engagement on law enforcement issues is already going on, having restarted in 2023.

And on Feb. 7, 2024, officials from both countries attended a meeting of the U.S.-Cuba Law Enforcement Dialogue, which promotes cooperation between the two nations’ police – the sixth such meeting since 2015.

That February meeting made it all the more likely that Cuba would be removed from the “not fully cooperating” list, which is, by law, reviewed every year. The question now is what that means for Cuba’s status in the U.S. as a “state sponsor of terrorism,” or SST – could that also be under review?

Unlike the “not fully cooperating” list, there is no requirement to review who is named a state sponsor of terrorism, either yearly or at any time.

On and off and on again

Cuba has yo-yoed on and off the list of state sponsors of terrorism. The communist island nation was first designated as a state sponsor of terrorism in 1982 by the Reagan administration. Cuba’s support for left-wing militant groups like Colombia’s FARC and National Liberation Army (ELN) in the 1980s was cited by U.S. officials as justification for its listing.

The Obama administration removed Cuba from the list in April 2015, having concluded that decades of sanctions levied against the country had not worked – Cuba retained its communist ideology. Simply put, we at the State Department thought it was time to take a new policy approach with Cuba.

Donald Trump waited until the very end of his four-year presidential term to add Cuba back on the list – and then had to rush to do so before leaving the White House.

In fact, the decision was made so late that the Federal Register Notice legalizing the decision was published on Jan. 22, 2021, after the inauguration of Trump’s successor, Biden.

According to the U.S. Embassy in Havana, the Trump administration was motivated by Cuba’s refusal to extradite 10 ELN leaders living in Havana.

But national security experts have criticized the decision, noting that Cuba hasn’t actively provided support to groups like ELN and FARC for decades.

Moreover, the Trump administration’s reason for adding Cuba back on the state sponsors of terrorism list went away in August 2022, when Colombia suspended the arrest warrant against the ELN commanders it had previously sought the extradition of.

In the hands of Havana

The consequences of being listed as a state sponsor of terrorism are more severe that being named as a “not fully cooperating” state. They include restrictions on U.S. foreign assistance, bans on the export and sale of defense – and some dual-purpose – items, and a range of financial prohibitions.

Cuba remains subject to both those restrictions and those stemming from the Trading With the Enemy Act – a law dating from 1917 but which has applied to Cuba since the missile crisis of the early 1960s.

As such, Cuba will not gain any significant immediate benefits from being delisted as a “not fully cooperating” state.

While countries deemed not fully cooperating with U.S. anti-terrorism efforts are prohibited from receiving defense services or articles, Washington is not in a position, due to other restrictions, where it would consider exporting military equipment to Cuba.

As such, the latest State Department delisting is more important for what it signals: that the United States is interested in expanding its engagement with Cuba. However, Cuba’s placement on the state sponsors of terrorism list – and trade restrictions under the Trading with the Enemy Act – will not make that easy.

But that may not be the point. Rather, the delisting of Cuba from the “not fully cooperating” list can be seen as a litmus test over the willingness of the Cuban government to open up to reforms.

Whether the U.S. follows up on the change in status with a decision to remove Cuba from its list of state sponsors of terrorism, allow Trading With the Enemy restrictions to lapse or even normalize relations is very much in the the hands of Cuba’s leaders. The next move will be theirs. They will need to demonstrate reform at multiple levels – economic, social and political.

But that will take time. Such reforms would require a major overhaul of the entire Cuban system, which requires a carefully managed transition away from state communism.

Enagement: An election risk?

But Cuba can begin to demonstrate now, and with success, that it will continue to fight against terrorism.

On this score, the results from Cuba’s last evaluation by the intergovernmental Financial Action Task Force in 2015 and the body’s 2022 follow-up report are promising.

Cuba is deemed compliant or largely compliant with 38 of 40 of the task force’s recommendations on terrorism financing, proliferation financing and money laundering.

If Cuba can demonstrate improvement in the remaining two areas – making sure that nonprofit organizations aren’t being exploited by terrorist financiers and that new technologies aren’t being used to fund nefarious activities – it could provide the Biden administration with more political leverage to begin the process of reviewing Cuba’s status as a state sponsor of terrorism.

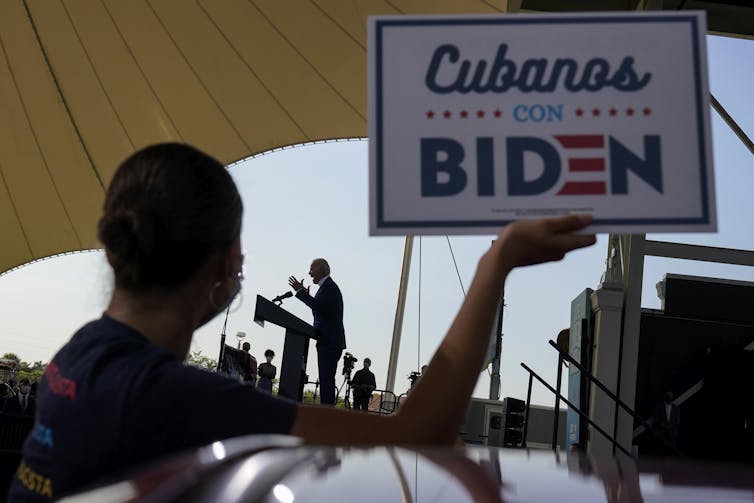

This leverage is especially important during a U.S. election year in which Trump is increasingly trying to paint Biden as a weak leader on the international stage. Dramatically shifting policy without concessions from Cuba may play into this narrative. It could also be an electoral risk, especially in Florida, where many anti-communist Cuban expats reside.

Enemies no more?

The last meaningful attempt by Washington to bring Cuba in from the cold fell flat. The Obama administration’s 2015 delisting of Cuba as a state sponsor of terrorism did not receive enough of a runway to see if it could encourage Havana away from communism before the Trump administration reversed course.

The Obama administration’s delisting was reversed in just under five years, which wasn’t enough time to test the theory that warmer relations could induce Havana to move away from communism.

The latest move to take Cuba off the “not fully cooperating” list could, depending on the outcome of the U.S. election in November, similarly become a victim of politics.

But the premise behind the State Department’s decision – much like the Obama administration’s delisting of Cuba from the SST list – is that person-to-person interaction is the best approach to pushing Cubans away from an ideology, communism, that has failed them in regard to their economic well-being and political freedom.

And engagement like that requires time – more than the four years of a U.S. presidential term.

It also requires patience, persistence and a willingness to consider lifting sanctions. After all, successful engagement and policy changes are hard to achieve if you continue to call your would-be partner an “enemy” and “sponsor of terrorism.”

Jason M. Blazakis does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.