During elections, we usually hear calls for the government and opposition to commit to increasing funding for hospitals.

While states are responsible for running hospitals, the federal government shares responsibility for paying for them.

The federal government also has the primary responsibility for keeping people out of hospital – through the primary care system, which includes general practice.

South Australia is the latest state to pressure both major parties to commit to greater levels of federal funding for hospitals.

Past hospital funding agreements didn’t account for increasing volume

Although state and territory governments are responsible for managing public hospitals, they have been reliant on federal government contributions since the 1940s, when when the states lost some of their taxation powers during World War II.

States and territories became even more reliant on federal government funding with the advent of Medicare in the 1980s, which gave all Australians the right to free public hospital treatment.

Up to 2011, the federal government and the states and territories negotiated how much the federal government would pay every five years. Negotiations were often accompanied by blame-shifting and acrimony between premiers and prime ministers.

Read more: Public hospital blame game – here's how we got into this funding mess

As a result, federal funding for hospitals was influenced by the timing of elections and the cycle of the five-year agreements, reaching a low of 38% in 2007, down from around 50%.

This was, in part, due to the fact that the federal government’s contribution did not alter when hospital activity went up.

Hospitals are paid for each procedure

Since 2011, the federal contribution to public hospitals has been based on the number and type of patients treated. This is known as activity-based funding.

All states and territories measure hospital activity by case “type”, weighted to reflect the complexity of a hospital’s activity. A lung transplant, for example, has a higher value than resolving an ingrown toenail.

The idea of measuring hospital activity and even using this as a basis for funding is not new. What was new in 2011 was using activity-based funding to determine the federal contribution.

Since 2011, the federal government pays 45% of the growth in the cost of delivering hospital services each year. This means the federal government’s annual increase in contribution can reflect both additional costs and activity.

State and territory governments are responsible for the remaining costs.

Since 2017-18, the growth in federal government expenditure has been limited to 6.5% each year. So even if a hospital performs many more procedures than the previous year, the federal government caps its annual expenditure growth at 6.5% more than the previous year.

Funding also encourages efficiency

Activity is one component of hospital funding, the other is the price paid for each unit of activity. The basis for this is the “nationally efficient price”.

The Independent Hospital Pricing Authority determines this price, based on its analysis of actual costs and assessment of unavoidable and legitimate variations in costs. For example, the 2022-23 efficient price for a hip replacement was deemed to be A$19,798.

This means the price is the same across Australia. Adjustments are made for patients from rural and remote areas, and for Indigenous patients. Sicker patients or those with multiple underlying conditions will fall into a different case type, with a higher price.

This provides a benchmark for comparing hospital efficiency as well as the level of funding the hospital will receive.

The goal is to treat more patients but keep costs constrained

The hospital funding system is designed to address efficiency by providing incentives to increase output, while constraining the growth in costs.

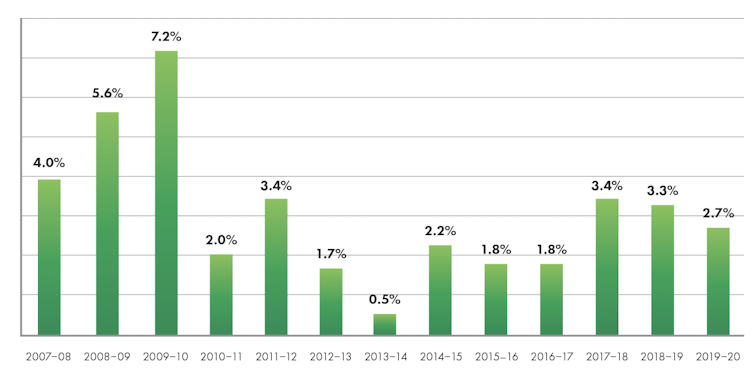

Since 2011, we’ve seen a substantial reduction in the rate of increase in costs, with an overall growth rate of 2.1%.

Annual growth in costs (per national weighted activity unit):

But there is further to go

The Independent Hospital Pricing Authority has, in recent years, started measuring hospital quality. This has created financial incentives for hospital managers to minimise errors, complications and unnecessary re-admissions. But so far, these are still quite targeted and only apply to certain procedures.

Activity-based funding is criticised for funding activity irrespective of the value of that activity. Just like all fee-for-service payments, it encourages a greater volume of services.

If the level of admissions provided is too low and the hospital is treating too few patients, then incentives to increase the volume are appropriate. But if some services do little to improve patient health outcomes, or if there is too little investment in keeping people well, then a change in incentives is warranted.

COVID has added a further complication. Hospital activity was decreased, particularly by canclling elective admissions to maintain spare capacity to handle COVID admissions. And costs were increased due to infection control requirements, such as personal protective equipment and staff on furlough after exposure.

The latest federal-state/territory agreement commits all governments to explore better ways to pay for health care. This will require not just thinking about hospitals but understanding their place in the health system and how to improve co-ordination across community and primary care.

If elected, Labor and the Coalition have both said they’re open to having further discussions with the states and territories about hospital funding.

Jane Hall receives funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council; and is a member of the Independent Hospital Pricing Authority

Kees Van Gool receives funding from National Health and Medical Research Council. He is affiliated with the Independent Hospital Pricing Authority.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.