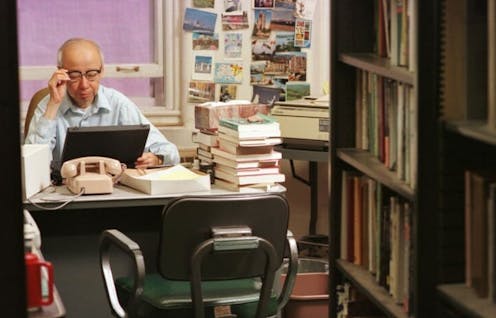

Yi-Fu Tuan, who died in Madison, Wis. on Aug. 10, 2022, was known as the most influential academic you never knew. Referred to as the father of humanistic geography, his most influential works dealt with the concepts of space, place and sense of place.

As we enter Geography Awareness Week, it’s important to recognize Tuan’s lasting impact on the field of geography.

Born in the Chinese city of Tianjin in 1930, his academic career took him around the globe, eventually leading him to the University of Wisconsin–Madison in 1983 where he attained emeritus status in 1998. Tuan received several awards including the prestigious Vautrin Lud Prize in 2012.

In his work, Tuan deals with spaces as general, objective areas, whereas places have meaning and memories. A sense of place is a deep emotional attachment to a place. In a world dealing with the challenges of the pandemic, refugee crises, political unrest and the impacts of climate change, his work is just as relevant as ever.

Landscapes of Fear

Tuan’s 1979 book, Landscapes of Fear, is intensely pertinent for our current pandemic reality. It’s an exploration into spaces of fear and how these landscapes evolve during our lives and vary over time. Tuan talked of the human response to disease as being a combination of common sense and fear. He speaks about many past responses to disease being reasonable, but also often going beyond the bounds of reason.

COVID-19 lockdowns and restrictions may have seemed acceptable but frequently created a terror of their own. Families desperate to see their older loved ones in long-term care facilities were unable to visit in their final days of life. Closed businesses and empty streets became a source of anxiety as many wondered if, once opened, these spaces would be safe to visit.

There was concern over whether travel was safe. Media was replete with a discourse of fear that led many to question whether it was a good idea to travel.

Read more: Fear of travelling: Canadians need to put travel risk into perspective

But that reduction in visitors to certain spaces created renewed appreciation for the places near our own homes. As restrictions eased, these landscapes were no longer feared. Our love of place overtook our desire for protection.

Transforming cityscapes

Tuan’s analysis in the chapter Fear in the City is also timely. Recent attacks like those in Saskatchewan, London, Ont. and Norway leave us anxious about streetscapes.

Tuan’s apt analysis showed us how those that govern cities focus more on economic and commercial activities, rather than social needs. And how the city itself can become a disorienting space. A labyrinth of disorder and social strife especially among those of different classes, races and ethnicities.

This disorder and social strife manifested itself visibly in the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery fostering greater mistrust in urban public spaces.

To offset these landscapes of fear, a counter-narrative emerged, transforming streets into spaces of sympathy for vigils, protests and marches.

That transformation is also apparent in the ongoing protests in Iran. The fight for freedom in public spaces has seen Iranian women leading protests against overbearing government control and many supporting these rights in public spaces around the world.

Place is security

Tuan’s concept of place became all the more significant during lockdown. The sanctuary of our most important shelter, the home, was challenged by the threat of an invisible virus.

But home as a secure place is a privilege not all have. As COVID-19 spread, hundreds fled homeless shelters, for fear of contracting the virus. Our most vulnerable citizens, including those experiencing homelessness, lacked security in place. Government action was needed, that for the time being, included sanctioned encampment sites.

Recent surges in Canada’s immigration highlight how migrants too need safe spaces to develop a sense of place.

As a geographer, I have studied how people establish a sense of place through multicultural festivals, ‘sensuous geographies’ and shared place identity. These intimate connections of place and belonging contribute to a sense of community. But when so many events were cancelled throughout the pandemic it had a drastic impact on communities, affecting our sense of place, shared memories and emotional geographies.

Because of their loss of place and space, migrants especially need help to connect to places. We could better assist them by understanding Tuan’s idea of topophilia — an intense sense of place based on social constructions and cultural identities.

Tuan said that we all have a deep need to connect through our senses. The pandemic has highlighted our deep need to connect physically rather than virtually. We have yet to truly understand its impact on our sense of place. With so many other sites closed, streets were re-imagined as places for dwelling, playing and connecting rather than merely spaces of transport and mobility.

Space is freedom

Space and Place is one of Tuan’s most highly referenced books. It’s a study about how people form emotional connections and attachments to their home, neighbourhood and nations, and how feelings about space and place are affected by time. What begins as undifferentiated space becomes place over time as we get to know it better and assign it value. A sense of place brings us security and safety, and we desire the need for openness and freedom in our space.

The so-called freedom convoy in downtown Ottawa highlighted Tuan’s notion of space being about freedom. While the encampment provided freedom to those who took part, it also took freedom away from residents whose everyday lives were suddenly restricted.

It took the safety and security away from residents who have a meaningful and deep sense of place there. The convoy raised questions about our democratic rights — whose freedoms were really being protected, whose were being denied and the controversy over security and policing in public places.

We could all learn from Tuan’s thinking. We must become humanistic caregivers of each other and the planet and avoid protectionist measures that perpetuate fear. Tuan was more concerned about what connected us, not what drove wedges between us. The intimate connection between space and place is highly nuanced. “We are attached to one, and long for the other.”

In these challenging times, we should all remember Yi-Fu Tuan and what makes us human first: the need for security in place and freedom in space.

Kelley A. McClinchey does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.