FORTY years ago was Newcastle's golden age of theatre, especially for the Hunter Valley Theatre Company (HVTC).

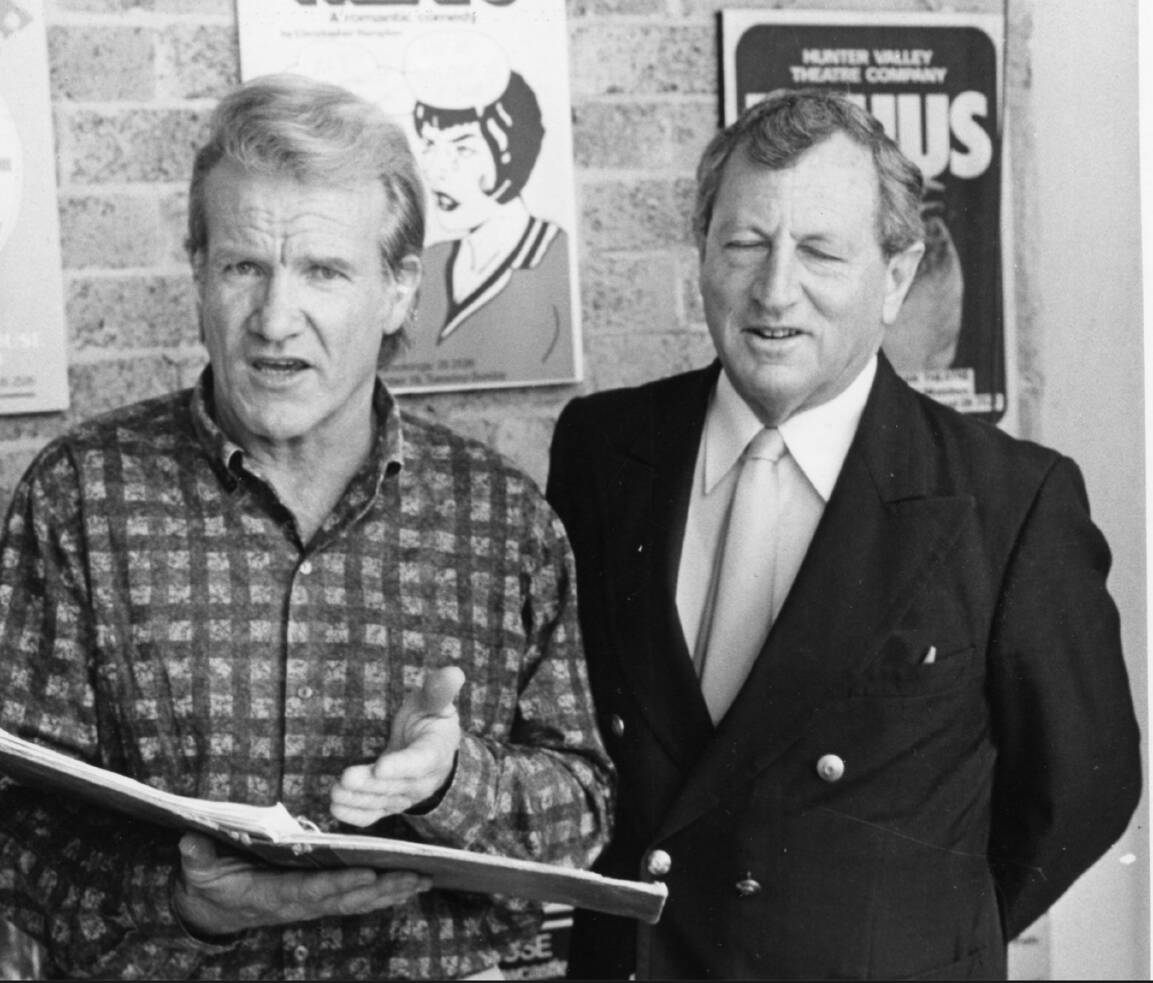

And at its heart was the craggy-faced, award-winning playwright John O'Donoghue, documenting the region's history and other topics with his carefully crafted words.

The HVTC always struggled to survive from its start-up in 1976, but somehow managed to persist until the mid 1990s when federal and state funding finally dried up and the city was much poorer for its absence.

The giant BHP Steelworks, with its belching furnaces, still dominated the city skyline at Port Waratah in the early 1980s, but it was living on borrowed time. It seems hard to believe now that back in 1964 the steel plant employed more than 11,000 workers. It was the real lifeblood of Newcastle. But, at the end, jobs had dwindled to fewer than 2000.

Today, oddly enough, many younger Novocastrians might be totally unaware of BHP's giant footprint here for 84 years. Today the vast waterfront site has been cleared, its future uncertain. It's the proposed site of a contentious container terminal.

The last whistle blew at BHP on September 30, 1999, but Hunter wordsmith O'Donoghue was there with a second dramatic oral history to 'bookend' the final chapter of Newcastle's steel colossus.

Both the HVTC and BHP Steelworks have gone, and now so has O'Donoghue. The playwright passed away aged 93 at Waratah on October 18.

His acknowledged masterwork was the play Essington Lewis: I Am Work (1981), about the life and times of BHP's general manager and industrial titan, the growth of BHP and, well, Australia really.

It started to mixed reviews and average box office receipts until, as the play's musical composer Allan McFadden said, noted Aussie playwright David Williamson realised how good it was and urged Novocastrians to see it. If not, they deserved to be horse-whipped for not supporting it.

The play, suddenly successful, took on a life of its own, winning the Sydney Critics Circle Award in 1985. It also toured most Australian states from Sydney to Perth for 16 years.

Then, to commemorate the closure of BHP Newcastle Steelworks, O'Donoghue produced a linked second play in 1999 strangely called No More The Fur Elise, No More The Bullied Bloom. It was about the beautiful Beethoven tune played to warn BHP workers when dangerous molten metal was being transported around the steel plant.

Playwright O'Donoghue wrote at least 10 memorable plays, ranging from 1982's In the Field Where They Buried Peter Pan (about Singleton) to Sao (in 1996 about the Arnott family dynasty). Or should that be 11 plays? For unknown to most probably, O'Donoghue has left behind the manuscript of an unpublished play. But more on that later.

The playwright, who was given an OAM in 2006, was born in 1929 at Waratah within sight of the BHP and later became a high school teacher and lecturer. At Newcastle Boys High at Waratah, he taught alongside Vic Rooney, who went on to star in many of his plays.

O'Donoghue's passion to write came from attending plays in London's West End in 1956-58. He taught initially at places such as Broken Hill and Lismore. His first trial play was about a flood he had seen at Walgett in the 1950s.

But the creative process of writing plays was not easy as he struggled over decades to "produce the perfect script". At O'Donoghue's recent funeral, his son Conal said his father sought creative inspiration through alcohol, but had also suffered the loss of his wife and the premature death of his daughter.

To his grandkids, the dramatist was just a "formidable, eccentric grandad", but to others, such as actor and broadcaster John Doyle (aka 'Rampaging Roy Slaven'), he was a magician with words with a poet's eye for the theatrical.

In his eulogy at O'Donoghue's funeral, and speaking on behalf of an early HVTC ensemble of Essington Lewis, Doyle recalled him as having a "rugged presence, being single-minded and obsessed with stories . . . his style of speech was as tough and as beautiful as ironbark.

"He loved talking, he loved a story. He brought out the best in us. For us actors (the play) was the ride of a lifetime," Doyle said.

The actor added that he remembered earlier attending a lecture by O'Donoghue who burst in, bellowing at students; "I'm mad about linguistics".

Older theatregoers today might remember O'Donoghue's first famous play, A Happy And Holy Occasion, from 1976. But he is most recognised for his later work about Essington Lewis.

I interviewed the playwright back in 2010, where he shared some insights behind his celebrated BHP play.

For example, O'Donoghue discovered during research that in the very early days of BHP, the board meetings would always start with a game of two-up.

He also produced an ingenious piece of theatre by having a boxing match on stage to represent the brutal 1922 wage negotiations between employer and workers.

And in 1989, one of the few remaining BHP relics left was "the stump". This huge solidified iron boulder was the base of BHP's historic No. 1 blast furnace from 1915.

"I always maintained that BHP should have etched on it all the names of the fellows who had been killed on site, but the company was very touchy about that," he said.

O'Donoghue freely admitted that writing for him was always difficult and nerve-wracking.

It's probably best summed up by a remark he made to then Herald reporter Mark Wakely in 1982 when he said: "Writing plays is a bit like wearing a hair shirt. I want to take it off and give it to someone else."

And now, what about O'Donoghue's last 'lost' play?

The two-act piece, penned several years ago, is 93 pages and is called Playwright And Saint.

"It's labelled as unfinished, but it looks finished to me, except for maybe correcting a typo," friend and author Paul Walsh revealed to Weekender.

"There are a few copies around. It's about Saint Therese who once wrote plays in a convent," he said.

"John was inspired to write the play by the strange experience of the visit of her bones to Newcastle, to St Therese's church, at New Lambton, ages ago. The play is dedicated to his late daughter Fiona," Walsh said.

"The dialogue is so John, witty and profound. And he was a perfectionist. I'm sure if the play had been performed in his lifetime, he would be rewriting act two while the performers were still onstage doing act one. His plays also had amazing names."

Walsh said the late Hunter playwright might have come across to some people as irascible or prickly, but he was, in some ways, deeply shy and old worldly.

"He certainly inspired me, showing me it was possible to have working-class dialogue on stage and still find an audience," Walsh said.

"Being shy might also explain the paradox of British novelist Graham Greene, who appeared to be acerbic, but the genius came out in his writing."

WHAT DO YOU THINK? We've made it a whole lot easier for you to have your say. Our new comment platform requires only one log-in to access articles and to join the discussion on the Newcastle Herald website. Find out how to register so you can enjoy civil, friendly and engaging discussions. Sign up for a subscription here.