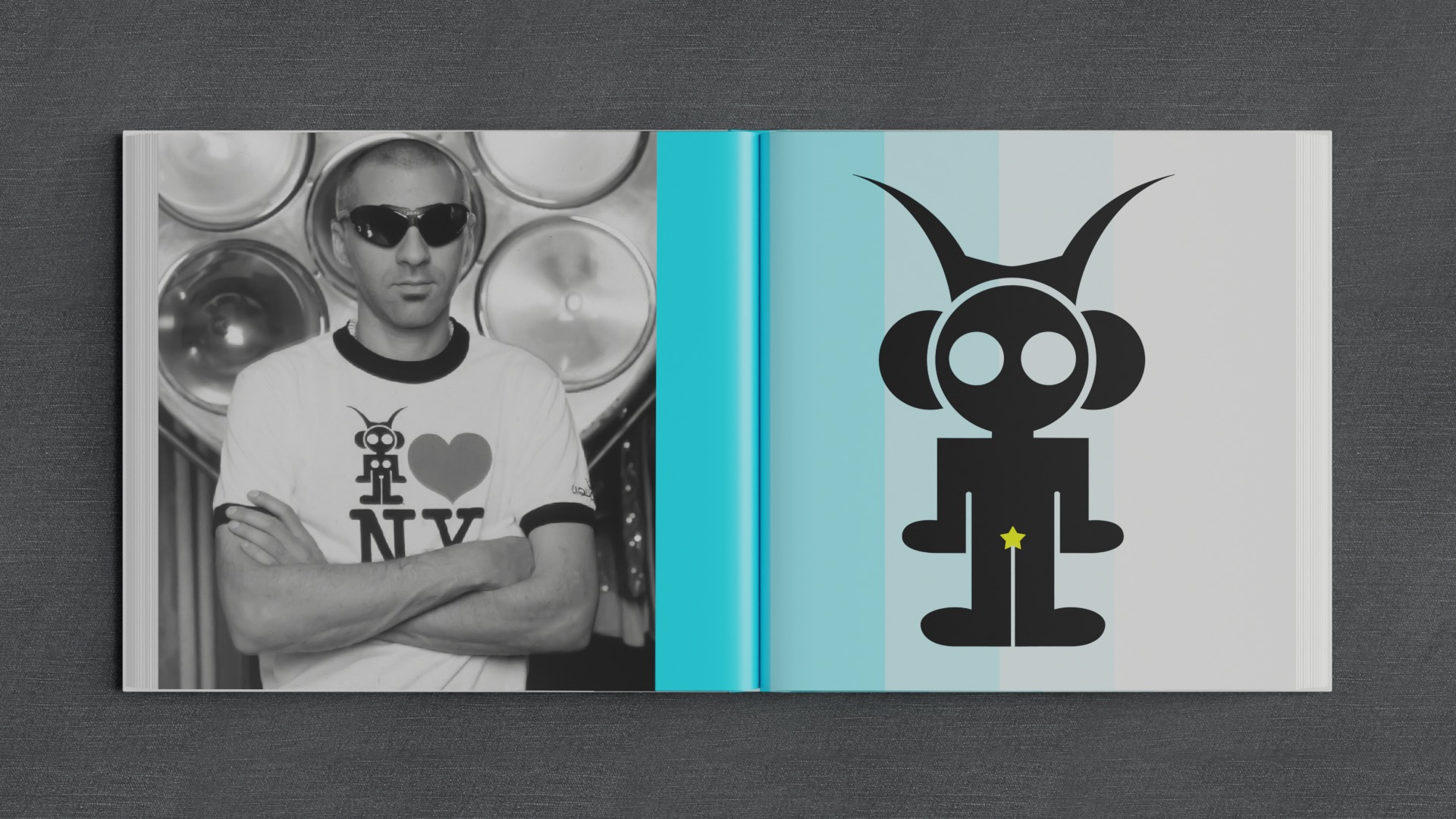

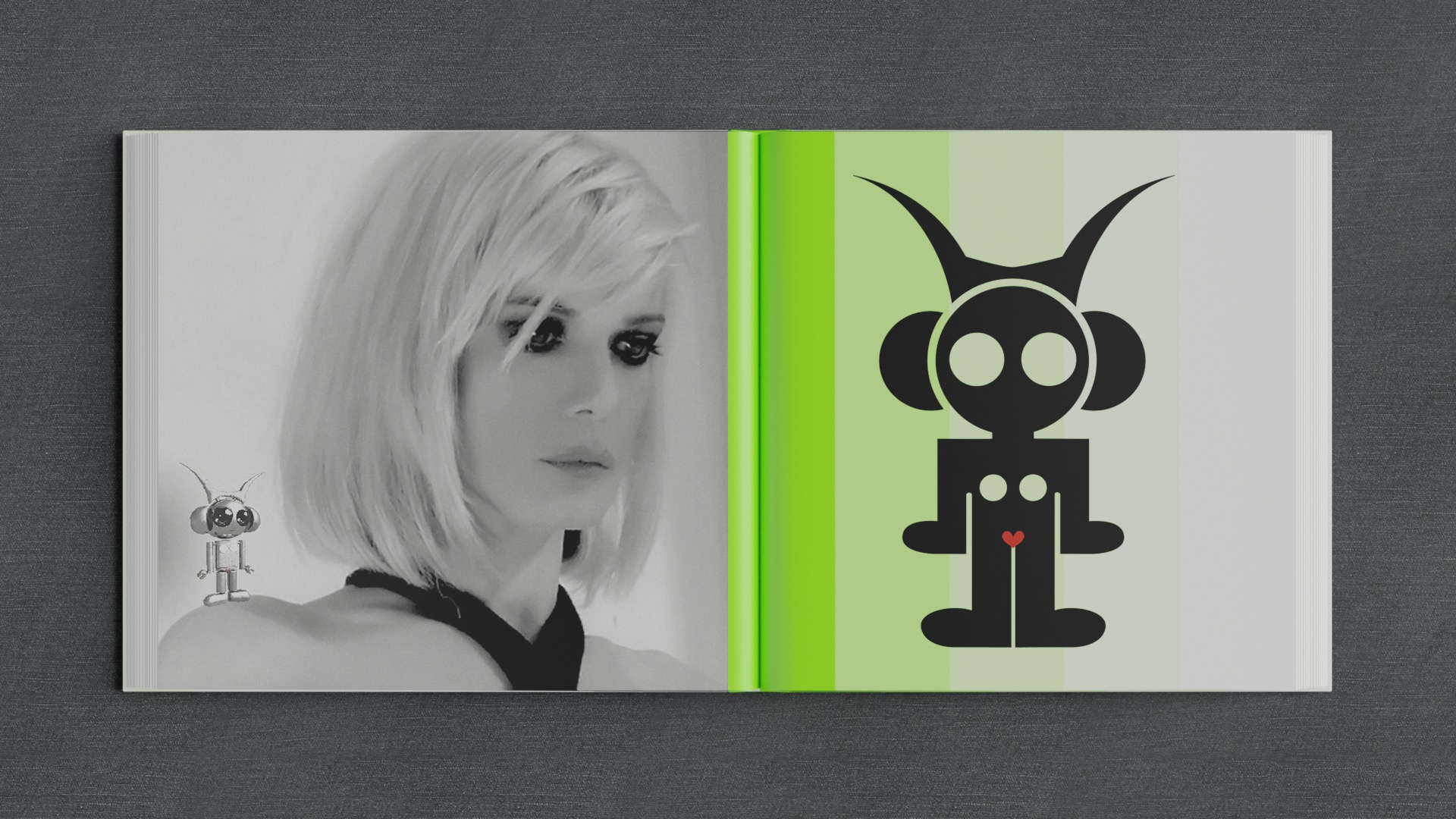

Liquid Sky was a store, but it’s more accurate to call it a scene. From the time the retailer opened its Broome Street location in 1990, eventually relocating to Layfette in 1992, it was the epicentre of New York’s creative subculture – a watering hole for ravers and skaters; teenagers and celebrities; hedonistic party monsters and dedicated artists who hung out inside its spaceship-like interiors and tried on clothes with the signature Astrogirl logo (an antennaed alien with a heart-shaped crotch) in inflatable dressing rooms. By the time Liquid Sky closed in 2003, it was already the stuff of legend – a New York institution that, like CBGB’s and Studio 54 before it, came to epitomise a particular time in the city’s history.

This month, Liquid Sky’s founders Claudia Rey (aka Rey Zorro) and Carlos Slinger (aka DJ Soul Slinger), with publisher and writer Marc Santo (who hung around the fashion store in its heyday) have launched a book, also called Liquid Sky, that documents its history. The 300-plus page tome contains hundreds of never-before-published photographs and interviews with key characters from the Liquid Sky scene, including Chloë Sevigny (who worked as a sales clerk) and other artists, musicians and club kids who hung around the store.

Liquid Sky: inside the new book documenting the cult 1990s fashion store

Rey and Slinger met in Brazil in 1982, when Rey was working as a model and Slinger was a veterinarian-turned-cosmologist developing a make-up that mixed suntan cream with fluorescent solar filters to create an otherworldly glow. Six months after meeting, the pair were married and opened up the first iteration of Liquid Sky in São Paulo, retailing their own cosmetics (lipstick for men, fluorescent eyeshadows) as well as Vivienne Westwood clothes and Rey’s own Dapper Dan-inspired collection called Copy Game, which featured overtly fake redesigns of clothing from major luxury brands like Chanel and Gucci.

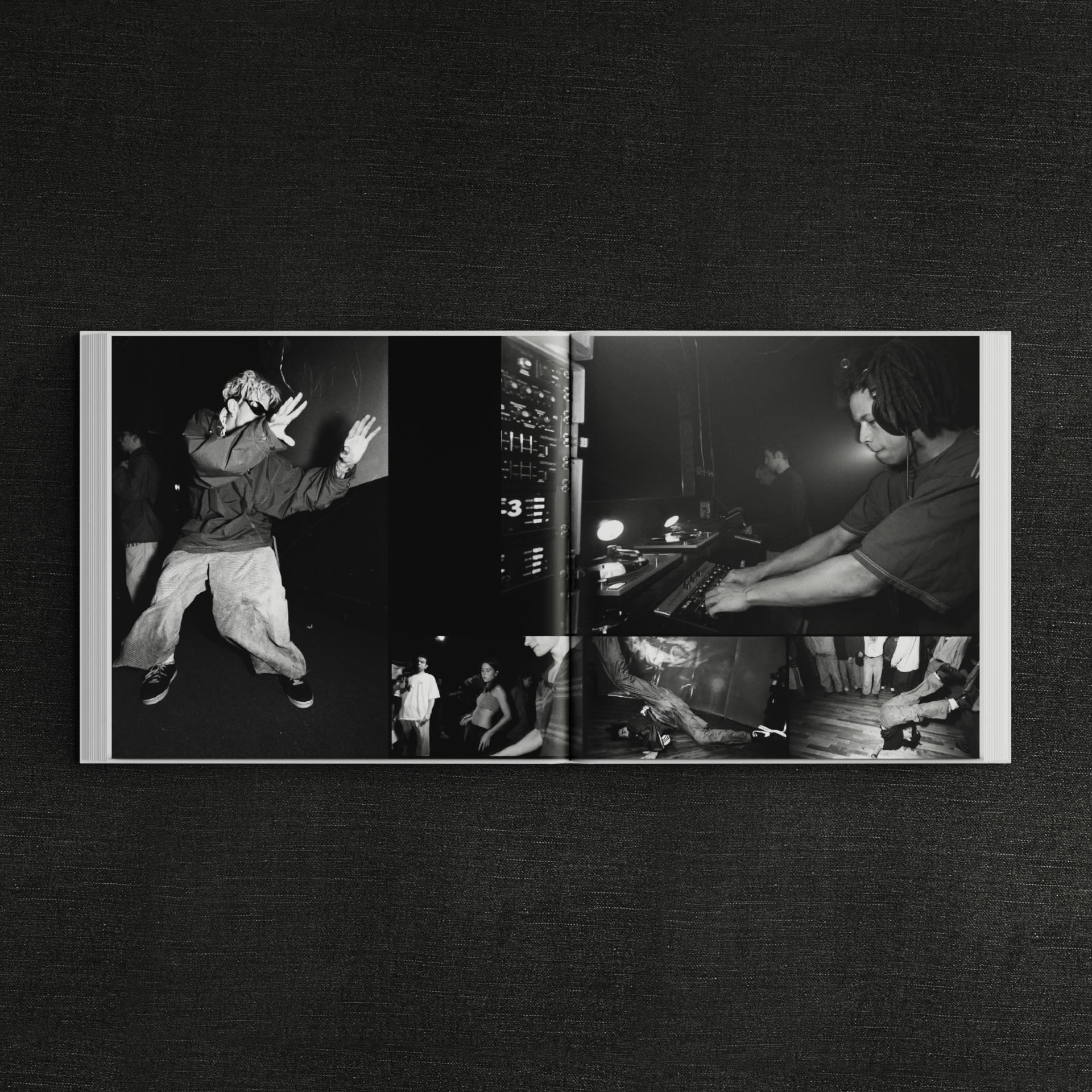

In 1989, the pair moved to New York and quickly became enmeshed in the rave scene that was burgeoning in clubs like Save the Robots and Danceteria. ‘We moved to East 2nd Street between Avenue B and Avenue C, and that’s where Liquid Sky New York was born,’ Rey says. ‘Because of all the things we did in São Paulo, we had an idea of what we wanted to do here.’

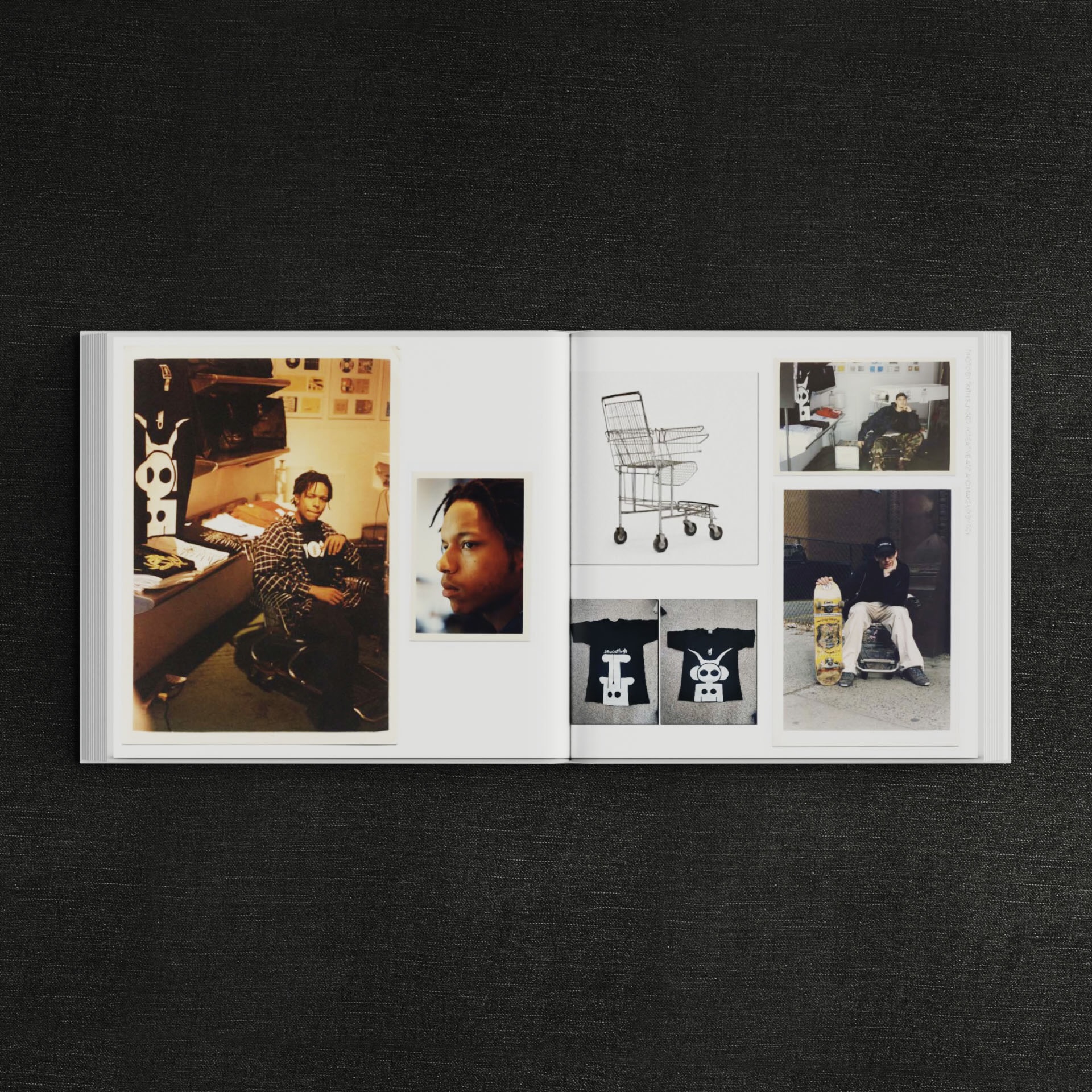

The original store on Broome was a ‘rave emporium’ carrying records, Rey’s clothes and brands that were involved with the rave scene at that point, like Sjobek, Conart and Alien Workshop. ‘When we arrived in New York, it was decadent and in crisis,’ Slinger says about the first shop. ‘We lived in the back of the store and learned as we went. We were silk-screening shirts, and people would come into the store and laugh.’

But soon ‘everybody who was doing something interesting in New York started coming in’, says Slinger.

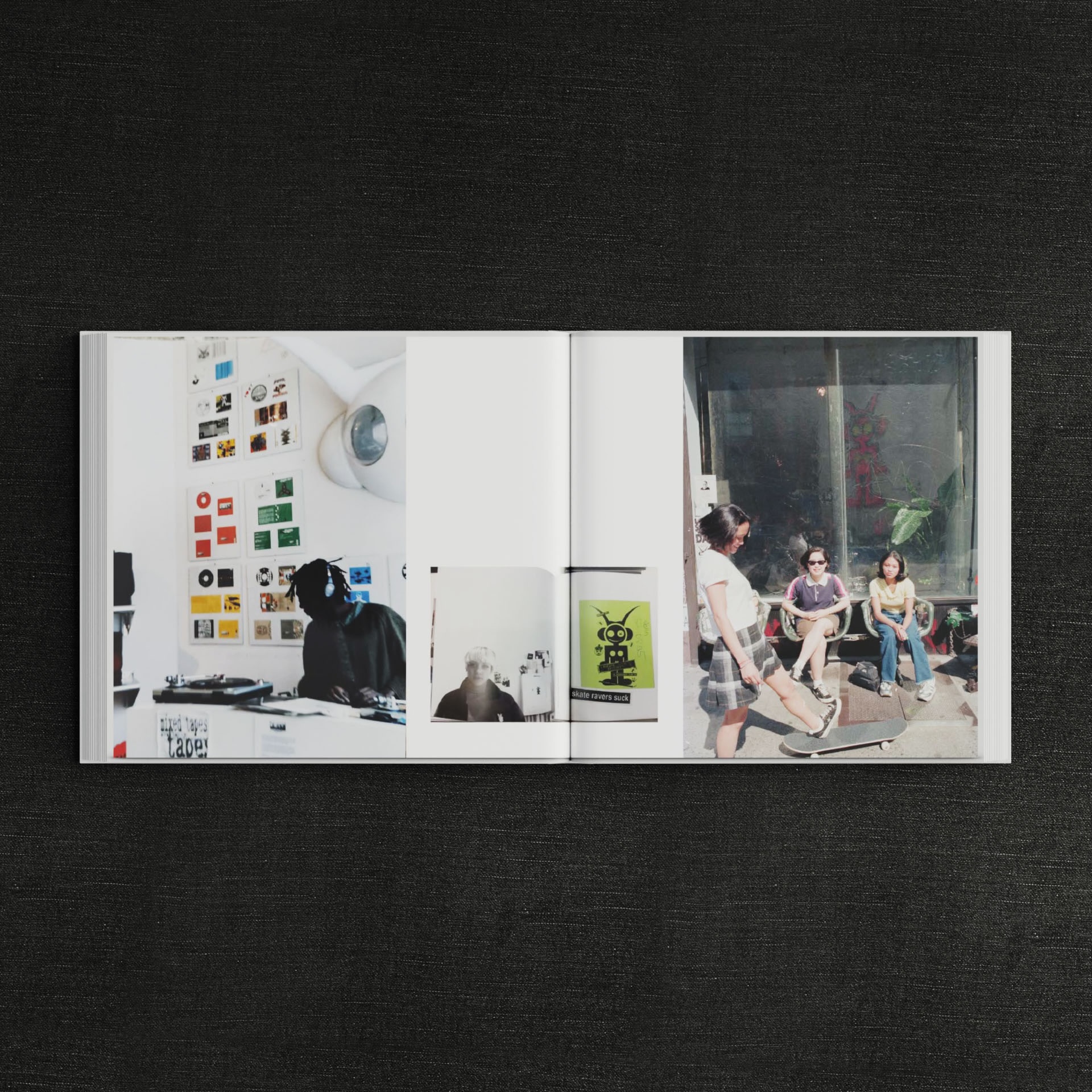

‘I mean, a lot of beautiful people,’ Rey agrees. ‘Artists of all kinds from all over the globe.’ By the time Liquid Sky relocated to Lafayette Street, it had become the daytime hangout for the rave scene, and fellow streetwear designers like Supreme, X-girl, and X-Large soon opened shop next door.

For Rey and Slinger, it was important that people felt comfortable hanging out in the store without the pressure to buy anything, and that it looked more like an art installation than a typical retail space. ‘I really wanted to create an ambience that felt infinite. I wanted it to feel high-tech like a spaceship,’ says Rey. ‘All the curves we put in there gave a floating sensation. I wanted people to come inside and have a happy floating sensation. I was just thinking freely and having fun. I wished it had no gravity too, so we would literally and laterally float.’

‘They created the waterfall window, and the shop became this spectacle,’ Sevigny remembers in her interview for the Liquid Sky book. ‘People would come in because of this arresting window, and nobody had ever seen anything like it before. The whole thing had this really DIY feel to it, and the whole operation was pretty janky. It was lo-fi and falling apart at the seams, but it was so visually arresting that people would come in and see this spaceship interior with Rita Ackerman paintings and just kind of stand there, like “Whoa.”’

Ahead of the launch of the book, I called Slinger at his home in New York and Rey at her base in London. In the book’s Sevigny interview, the pair are described as ‘cosmic characters from another world’, and it's true that even over Zoom the conversation feels oracular, touching on topics like the existence of aliens, and the creative possibilities generated by new technology.

Liquid Sky, the pair tell me over the course of our call, was not the result of a considered plan; rather, it was the byproduct of their constantly creating new work, experimenting and engaging with the people around them. ‘One thing the book made me realise,’ Rey tells me, ‘is that back then I was so sure of what I was doing and I really want to get back to that mindset. I don’t know if it’s because of the media, but these days everything feels so careful. I think the one thing that younger generations have to hear over and over is to stop trying to follow others. You get so worried with that, that you stop creating for real.’

When I ask them why they think so many young people today are looking back to the 1990s for inspiration, Slinger responds that it’s a byproduct of a natural cycle, a shift from a ‘me’ to an ‘us’ mindset that exited in Summer of Love in the 1960s and reappeared in a ‘cyber’ aesthetic with the rave scene in 1990s and will appear in a new aesthetic form now. ‘The rave thing was Woodstock brought to the future,’ says Slinger. ‘And I think if the kids recoup those images with this new technology that they have in hand, then they can produce anything they wish.’

It’s a hopeful message about the future at a time when it’s easy to feel negative about it. But, as Slinger points out, Liquid Sky and the rave scene it fostered were founded in pursuit of ‘utopia and chaos’, just like all scenes that came before it and all the ones that will come after it. ‘The most important thing is to educate yourself, to have curiosity,’ Slinger says. ‘Then you can better understand your particular space and time and what you can do – and you can do a lot.’

The Liquid Sky book, $65, published by Emperor Go! is available for pre-order on the Liquid Sky website, along with accompanying merch.