For better and worse, nobody embodied the counterculture like David Crosby. Close your eyes now and you’ll picture him at his ‘60s peak, as an idealistic young rebel in fringed jacket and Obelix moustache, offering his worldview from a West Coast stage.

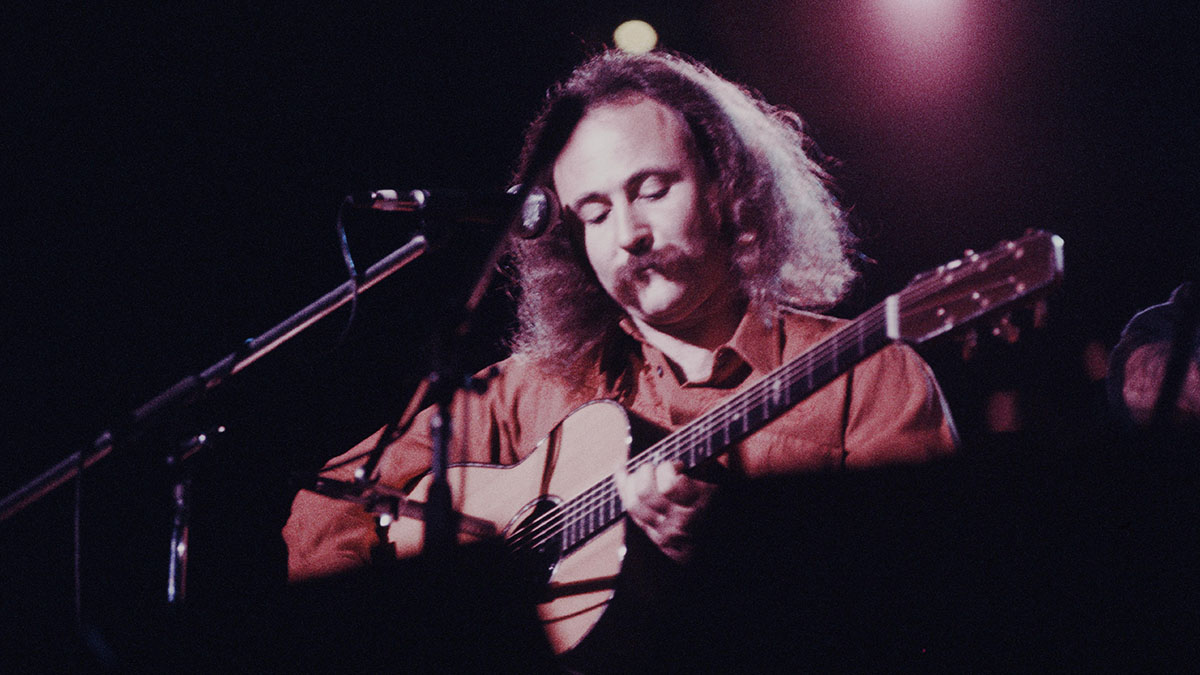

Think of his music and you’ll recall the wild-honey voice that defied age and gravity all his life, or those underrated guitar skills, standing out even in line-ups that featured such stone-cold pickers as The Byrds’ Roger McGuinn and Stephen Stills of Crosby, Stills & Nash.

Quite rightly, it’s this benevolent side of ‘Croz’ that was evoked by the well-wishers when the 81-year-old passed over on 18 January. But it’s telling that even the most loving eulogies came with a caveat. “David and I butted heads a lot over time,” wrote Stills. “They were mostly glancing blows, yet still left us with numb skulls. I was happy to be at peace with him. He was without question a giant of a musician.”

As a singer, writer, player and mouthpiece for rock’s most outspoken generation, Crosby’s genius was indeed undeniable. Yet those qualities were only one facet of a complex man whose estimation of himself as controlling, egotistical – “the world’s most opinionated man”, as he put it on CSN’s Anything At All – would at times have been endorsed by his closest friends.

Depending on when you encountered him, Crosby could be the blissed-out utopianism of the hippie dream or its bloodshot-eyed reflection in a cracked mirror. He could be the peace and love personification of 1969’s Woodstock festival or the pistol-packing paranoia of its evil twin, Altamont.

In his troubled late 1970s and ‘80s, weighing Crosby’s discography against his rap sheet was too close to call. Perhaps The Simpsons said it best when the singer guested on the show, with Springfield’s town drunk Barney thrilled to meet his role model but bemused to learn Crosby was famous for something other than excess: “You’re a musician…?”

Born in Los Angeles on 14 August 1941, David Van Cortlandt Crosby briefly suggested he might follow his Oscar-winning cinematographer father into the business. “He’d be shooting at a little fake Western town out in the valley and I’d get to run around,” the singer told Uncut. “It was something he was a little reticent to do ’cos I was kinda a wild kid and he was a very serious guy. My dad was not a fun guy – he was not a good dad, either.”

But Crosby had spent his teens listening to ’50s jazz and buying folk records: he cites Woody Guthrie’s Bound For Glory, Joan Baez’s self-titled debut and the harmonies of Peter, Paul and Mary as key influences, while claiming to have “picked up the guitar as a shortcut to sex”. That passion won out, making him ditch a drama course at Santa Barbara College to tumble onto the 1964 folk circuit and the orbit of McGuinn and Gene Clark.

“We went to see A Hard Day’s Night,” the Byrds’ 12-string legend told this writer in a 2011 interview. “After we came out of the cinema, David grabbed a lamppost like Gene Kelly in Singin’ In The Rain and said, ‘That’s what I want to do! I want to be in a band like The Beatles!’”

This proto-Byrds line-up shuffled, with Crosby trying his hand at bass until the arrival of Chris Hillman saw him take on rhythm guitar and high harmonies. “His right hand was good at doing very fancy strumming,” noted McGuinn in the same interview. “David could do multiple ups and downs, a good rhythm player. He was bright, gifted and very opinionated. That’s just the way he is.”

As it turned out, Crosby had bigger plans than emulating The Beatles – or continuing to lean on the Bob Dylan songbook, as The Byrds had on 1965’s debut album Mr Tambourine Man. While Clark’s early dominance kept him at bay, his exit let Crosby submit standouts like the tumbling I See You, the wistful trill of What’s Happening?!?! and at least part of the freeform psychedelic masterpiece, Eight Miles High, which channelled John Coltrane and Ravi Shankar to mind-expanding effect. “I think that’s the best thing we did,” Crosby told Vulture. “But we did a number of them.”

Still in his mid-20s, Crosby’s writing was already sophisticated beyond his years. By 1967’s Younger Than Yesterday album, he pushed hard for the inclusion of gems like the spooky, jazz-inflected Everybody’s Been Burned, and Mind Gardens, a song that spiced the familiar Byrdsian jangle with faint unease and underscored his mastery of mood.

But his growing dominance brought friction. One contentious move was to eliminate his bandmates’ vocals from Lady Friend, rendering the track a blissful wash of Crosby harmonies. “I was a thorough prick,” he reflected of his steamroller approach to the studio. McGuinn preferred “a little Hitler”.

As a personality, Crosby’s onstage sloganeering and capacity to hold court at interview was anathema to the fame-shy Byrds line-up. The inevitable happened in October 1967, with Crosby fired halfway through sessions for the following year’s The Notorious Byrd Brothers (the band retained his soft-focus Draft Morning and the brilliantly slippery time signature of Tribal Gathering).

“They came zooming up in their Porsches,” remembered Crosby, “and said that I was impossible to work with and I wasn’t very good anyway and they’d do better without me. Fuck ’em.”

That short run in The Byrds had almost secured his immortality. But as Crosby told Uncut, when he first sang harmonies with ex-Buffalo Springfield man Stills and Graham Nash of The Hollies, he foresaw a musical direction that energised him. “I encountered Stephen and he swung really hard. He could play a kind of music The Byrds couldn’t play and it appealed to me tremendously. I wanted that, and I really didn’t want to go in the direction that Chris and Roger wanted to go in, of becoming more country.”

CSN proved an instant smash (the band’s self-titled 1969 debut has since gone four‑times platinum) and Crosby seemed as snug as a songwriter as he did within the trio’s close harmonies. Composing on acoustic guitar – he favoured the Martin D-45, having bought three of them that year – he swiftly served up Guinnevere, a hypnotic stunner in an unusual EBDGAD tuning that, like so many of Crosby’s best songs, gave the impression of floating.

“The time signature is odd. The structure of the song is odd. It’s me all over,” said Crosby. “I don’t know if ‘quirky’ goes far enough to describe my guitar style. It came from a very odd place, man. I’d listen to jazz keyboard players like Bill Evans. They’d play dense chords. I wanted those chords. But I couldn’t play ’em in regular tuning. That’s what pushed me. As soon as I put the guitar in another tuning, I said, ‘Oh yeah, this is what I was looking for.’”

Recruiting Neil Young – and achieving career-best sales figures – 1970’s Déjà Vu was arguably the musical peak. But CSNY’s chemistry was souring, while the shattering loss in a car crash of Crosby’s girlfriend Christine Hinton left the singer bereft. For now, he could still deliver the goods, though if you listened a little closer to Déjà Vu’s classic choppy rocker Almost Cut My Hair, its author sounded ill at ease (‘It increases my paranoia/Like looking in my mirror and seeing a police car’).

There’s absolutely no question that taking drugs enhanced my creative process. Taking hallucinogens probably helped, in part, but obviously drugs are all different and cocaine and heroin took me right down

David Crosby

More troubling still, on his brilliant 1971 solo album, If I Could Only Remember My Name, was the wordless swoop of I’d Swear There Was Somebody Here. “I had this vision that my girlfriend who had gotten killed, Christine, was standing right next to me,” Crosby told Vulture of the song’s heartbreaking genesis. “I could feel her there, her presence. Then I improvised that piece of music while thinking about her then and there. I think you can feel it. If you listen to it, you’ll know.”

While CSNY stuttered along in various permutations, Crosby’s output dried to a trickle as his personal life spiralled. The years ahead would bring the singer to some humiliating lows. Heroin and crack cocaine – and the shadow men who supplied them – became his constant companions, his neglected body a tapestry of scratches and sores. In the mid-‘80s, Crosby hit rock bottom, serving a nine-month jail stretch for drugs and weapons charges.

“There’s absolutely no question that taking drugs enhanced my creative process,” he told Classic Rock in an interview in 2021. “Taking hallucinogens probably helped, in part, but obviously drugs are all different and cocaine and heroin took me right down. I ended up in a Texas prison. There’s no way around it, it nearly killed me, destroyed my career, fucked me up bad.”

When CSNY regrouped for Live Aid, commentators took a double-take at the cadaverous figure in their midst. As Spin put it: “A 14-year addiction to heroin and cocaine has left David Crosby looking like a Bowery bum.”

Few were expecting a happy coda from this hopeless case, but Crosby still had a little magic left in him. “I wrote Compass in prison about waking up from drugs,” he told Vulture of the highlight from CSNY’s 1988 American Dream, which he considered the start of his redemption. “It was when I realised that I was going to come back, I was going to get sober, I was going to be able to handle it, and then I was going to write again – which was crucial. I was sober for the first time when I was released.”

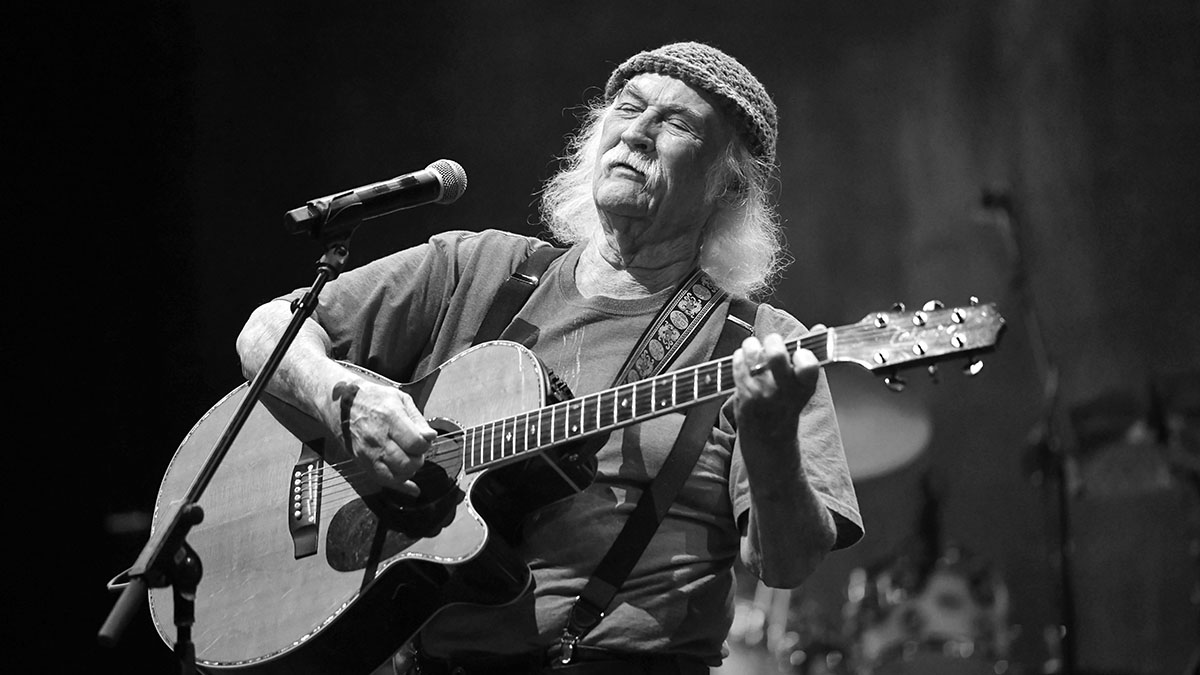

Cleaning up for good in the post-millennium – “I’m not clean,” he corrected this writer, “I still smoke pot” – Crosby’s late period produced some of his best work, including 2018’s Here If You Listen, which he considered “as good as anything I’ve ever done”. Alongside that, his playing continued to evolve (“I’m a picker on acoustic now and mostly a strummer on electric”).

And while physically, he softened into an avuncular silver bear, the young firebrand still raged whenever a journalist proffered a dictaphone. “Trump,” he told Guitarist, “is like an eight-year-old kid that’s broken into his dad’s office and he’s pissing all over the papers ’cos he never got to play in there.”

If he stayed true to his politics, then Croz was also faithful to his love of music to the end. He told this writer of his nightly habit of “taking a guitar off the wall, smoking a joint and playing for hours”. He added that the period he was most proud of was “tomorrow”. In the days after his death, it emerged that Crosby was readying new material, perhaps even taking it on the road. “He seemed practically giddy with all of it,” guitarist Steve Postell told Variety.

It was not to be. Yet for all those wasted years, the astonishing body of work we inherit from David Crosby – not to mention his thumbprint on how we view the world – will resonate. “I’m working on leaving behind my best,” said the singer, and he certainly achieved that.

The tributes were as grand as the company Crosby had kept, with the stars to salute him ranging from David Gilmour (“I’ll miss the Croz more than words can say. Sail on”) to Jason Isbell (“Grateful for the time we had”). But perhaps the final word should go to the man with whom Crosby clashed most viciously yet sang most beautifully.

“It is with a deep and profound sadness that I learned my friend David Crosby has passed,” wrote Nash on Instagram, alongside a shot of his former bandmate’s well-travelled guitar case. “I know people tend to focus on how volatile our relationship has been at times, but what has always mattered to David and me more than anything was the pure joy of the music we created together. David was fearless in life and in music.”