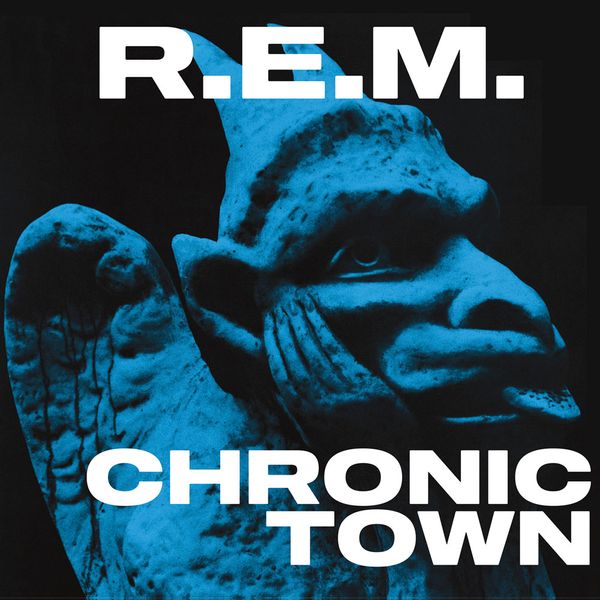

On August 24, 1982, R.E.M. released their debut EP, "Chronic Town." Even today, it's difficult to categorize the five-song release: Bookended by the ringing, yearning "Wolves, Lower" and the rhythm-heavy "Stumble," the EP turned underground rock on its head, adding equal parts delicacy and tenacity to the music.

"Chronic Town" ... turned underground rock on its head, adding equal parts delicacy and tenacity to the music.

That magical alchemy endured across the decades. In high school, I borrowed the cassette from my town's library for weeks on end, renewing it at the end of each cycle. "Chronic Town" was also my go-to soundtrack for getting ready before school. The 20-minute release was the perfect length for eating breakfast — cereal piled high with multiple heaping spoonfuls of sugar — while reading the morning newspaper and mentally recharging for the long day ahead.

If I was running late (a rather common occurrence, as I wasn't a morning person) I wouldn't make it through the whole EP. At other times, I'd make it through to the last song, "Stumble," which was introduced by the sound of Michael Stipe chomping his pearly whites and announcing, "Teeth!"

Mitch Easter, who co-produced "Chronic Town" and would go on to co-produce R.E.M.'s first two albums, "Murmur" and "Reckoning," with Don Dixon, contributed liner notes to a new 40th anniversary reissue of the EP. The notes are a delight — detailed and informative, and full of trivia even the most hardcore R.E.M. fans might not know. For example, Michael Stipe recorded one song with a garbage can over his head, but nobody can quite remember which song that was.

Easter's assessment of R.E.M. at that time is also understandably spot-on. "They all told me that they were very deliberately figuring out their sound, and what they were going to be about," he writes. "The fantastic thing is they landed in this magic intersection of understandable + mysterious, in perfect proportion. You could rock out at a show with the people or listen in your bedroom and feel like only you and they were in the same secret world."

In another spot, Easter writes that guitarist Peter Buck "notes that the band specifically didn't want to make an album yet. Even if they had enough songs to make an LP, they wanted to proceed incrementally."

Speaking to Salon today, the band's advisor, Bertis Downs, remembers wondering at the time why the band wanted to do an EP, though hindsight has offered some wisdom. "I think it was really the songs they felt the most strongly about that were finished," he says.

But after "Chronic Town" was done — and Downs heard how it turned out — he says it taught him an important lesson going forward: to let the members of R.E.M. take the lead on creative choices and directions. "I learned: 'It's their band. It's their decision,'" he says. "And [it became] 'Let's make it work.'"

"Somehow R.E.M. 'ticked all the boxes' of the new music era and equally transcended them. They were like a punk band live, but wrote songs that didn't seem punk at all."

This was certainly a successful strategy, as "Chronic Town" placed No. 2 on the EP list on The 1982 Pazz & Jop Critics Poll and set the stage for R.E.M. to release their debut album, 1983's "Murmur." The rest, as they say, is history.

Easter — who also fronted frequent R.E.M. tourmate Let's Active — shared some additional thoughts about making "Chronic Town" with Salon via email.

Reading the liner notes, what came to mind is reading about how an album like the Beach Boys' "Pet Sounds" was made: experimentation with techniques, using environments and other things around for sounds. Why did this approach to recording make sense for R.E.M. at this time and the batch of songs they had?

Thanks for this flattering comparison! So many of my favorite records give me the feeling that everybody involved was motivated by the love of sounds, unconcerned with how the record would fit with the conventional wisdom of the era. When I heard the songs the band had for "Chronic Town," I thought we had the perfect situation to hit a place between the familiar and the slightly off-kilter. I mean, that's in the songs, but ideally a recording can bring out the intrigue a little more.

In hindsight, what made R.E.M. so unique and different from other young bands who were also striving to grow and become a success at the time? What made the band stand out?

Thinking about the band now, I'm struck by how they were simultaneously "of their time" but not defined by it. Maybe that fact was crucial for them to ultimately reach so many people. When "Chronic Town" was made, we had all these strongly held views about music, as The Kids disassociated themselves from mainstream commercial music — opinions about synths, the kind of guitar tone you had — there were some serious dogmas happening! But these notions put energy into things.

Somehow R.E.M. "ticked all the boxes" of the new music era and equally transcended them. They were like a punk band live, but wrote songs that didn't seem punk at all. People didn't know what Michael was saying, but they knew he was speaking to them. The band was really hard to pin down and it served them well, especially in a kind of anti-(whatever) music scene.

In concert, Let's Active supported R.E.M. from the very start — and even played some shows with the band right before the January 1982 "Chronic Town" sessions. Did having this exposure to the band's live show give you specific insights into the best ways to record the band — or ideas on ways to approach the recording session? If so, in what ways? (I ask this especially because you note this in the liner notes: "To me, stage and recordings are complementary parallel universes.")

I don't mean to sound flip when I say that I like for recording to feel like finger painting, but I really do think that, especially with bands. When everybody gets together in the studio there's something in the air and I think you just go with it. The atmosphere on "Chronic Town" was: Let's go! And, freedom, exploration, and a little bemused contrariness. It was great, nobody was worried about anything. I suppose some of this was informed by what I'd seen of them so far, mainly their confidence. They had their own pretty serious quality control, which they trusted. This leads to boldness and greatness!

When you (and Don Dixon) went on to work with the band on "Murmur" and "Reckoning," what insights or approaches did you take from the "Chronic Town" sessions to the later ones?

As is well-known now, things were different once they signed to I.R.S. [Records] and had worked, at the suggestion of the label, with real producers (as opposed to us unknown hillbillies, as I like to say), which had not been a happy situation. So the confidence they had on the "Chronic Town" sessions had been shaken and I think they had a sense of dread about the whole enterprise. They seemed to have gone from loving recording to seeing it as a place where everything gets ruined.

I think maybe the most important thing Don and I accomplished was to get them un-freaked out about recording and establish a new range of sounds that suited them. They were, wisely, not interested in a lot of the currently fashionable sounds, and they were prepared to make a record that was essentially live-in-the-studio. Don and I thought that a record like that would sell the songs short, since "records" really are another universe, and it's a shame to not make some use of that.

The fast version of "Wolves, Lower" surfaced on a bootleg at some point — and, in hindsight, it is head-spinningly fast! Why did the band choose to recut it at a later date, do you recall?

I think maybe we all started thinking that the fast version was just a little breathless, although it's definitely an impressive testament to youth! When I spoke to all of them recently, most of them had completely forgotten about the two versions.

As a musician yourself, did you leave the "Chronic Town" session with any takeaways you applied to your own songwriting, bands or live show?

Songs like "Wolves, Lower" were indeed inspiring to me as a songwriter and guitar player because I immediately loved the song, it didn't remind me of any other song, and it was one of those great examples of how you can take the standard rock band setup and do something that feels different and interesting. Being fired up by music in general is good for the soul and everything else!

You recently worked with Peter Buck and Mike Mills as part of the new Baseball Project record. Forty years later, how has it changed — or not changed — working in a recording studio with them?

Peter and Mike are always ready to jump in and do their parts. They don't require a bunch of takes or fixes, [and] they're quick learners and accurate players. The Baseball Project is an altogether different band, but in so many ways the session was exactly like what we did 40 years ago. We even used some of the same equipment. There was a good bit of In the Grand Tradition going on, I'd say.