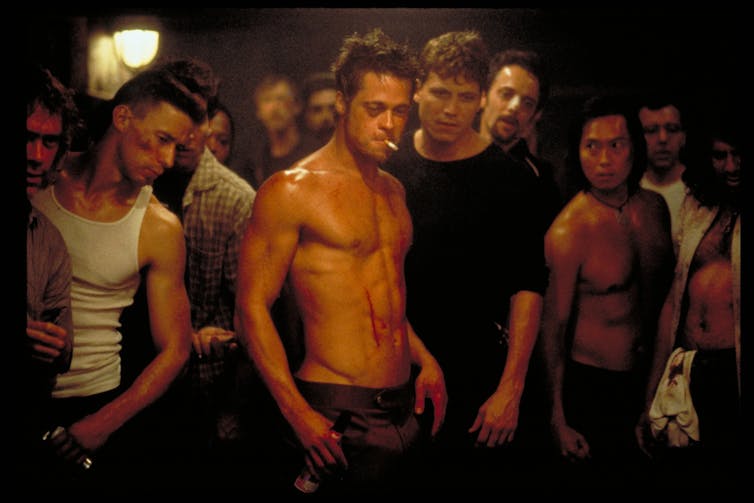

Project Mayhem is an all-male cult – but unlike the real cults that Sarah Steel writes about in Do As I Say, Project Mayhem is fictitious. It comes from the mind of Chuck Palahniuk in his masterpiece novel Fight Club, a dark exploration of contemporary masculinity that describes how a group of men come together to form a fringe group with fringe ideas – and how this can go wrong.

Review: Do As I Say: How cults control, why we join them, and what they teach us about bullying, abuse and coercion, by Sarah Steel (PanMacmillan)

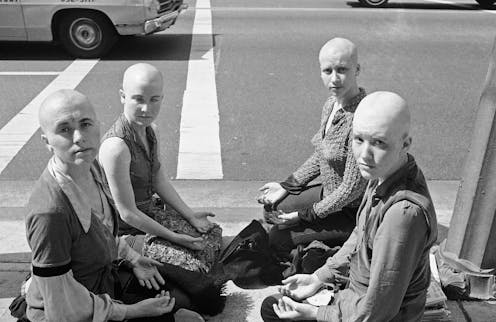

Project Mayhem exhibits many key elements of what we see in cults.

In Do As I Say, Steel (creator of the podcast Let’s Talk About Sects) explores how cults usually exhibit some of the following attributes: they have unique in-group language, they require intense work schedules of members, their leaders will often deliver endless sermons, and they will restrict access to media. Members are directed not to ask questions, and professional help or healthcare and outside information are restricted.

Perhaps most importantly, cults use a method that experts now refer to as coercive control – an act or a pattern of acts of assault, threats, humiliation and intimidation or other abuse that is used to harm, punish, or frighten their victim into conforming.

This form of psychological manipulation is a key part of the fabric of domestic abuse relationships.

Read more: It's time 'coercive control' was made illegal in Australia

Triggering events

Steel reveals members of cults usually experience a triggering event prior to joining. This is backed up by various scholarly sources who’ve written about religious conversion and those who join extremist groups.

A triggering event may be something like a divorce, the death of a loved one, or another event that’s traumatic, or perceived as traumatic. These themes have been noted by sociologists such as Emile Durkheim and Max Weber, who wrote about how fringe religious groups come about during times of societal unrest.

For Durkheim, religion (and other social norms and values) act as a kind of social “glue”. In times of rapid social change, existing rules, habits and beliefs no longer hold. This produces an environment ripe for exploitation – usually by a charismatic man with all the answers to your problems.

Durkheim referred to this personal feeling of change (loss of existing rules, values, beliefs) as “anomie”, which basically means everything in your life has gone to shit, producing a desperate need to find meaning, belonging and control again (or perhaps for the first time).

Read more: What kind of person joins a cult or joins a terror group?

Cults and control

This is where the study of cults gets interesting and even controversial. As Steel outlines with countless examples, cults often seek to control every aspect of one’s mental and physical existence.

Unless one is born into the group, as Steel also notes, people (overwhelmingly women) choose the group for themselves, albeit without information about its darker aspects. The question is: why on earth would anyone find groups like these appealing?

The need for order, structure and certainties are part of the answer. These have been shown to be common psychological traits for those who lean more to the political right. However, research is showing these factors are growing universally common.

This is the tragedy of cults and other extreme groups: as Steel notes, they exploit freedom of belief, freedom of association and freedom of religion – with often abusive and damaging outcomes.

Everyone loves freedom, for good reason. It’s the foundation of liberal democracy. But unrestrained freedom without a sense of structure, meaning, and order is psychologically unstable – for societies and individuals.

Take, for instance, the feminist issues Steel raises in relation to cults: curtailment of reproductive rights and rights for children, and issues with problematic male leadership. Within many cults, Steel notes, women’s rights are severely curtailed through controlling relationships, limited choices and subservience to the often-male leader, or men in general.

As Steel explains, Australia has been clear that when it comes to immigration, if imported misogynistic belief systems clash with Australian values, Australian values (including women’s rights) should win. But cults appear to slip through the cracks, as they can hide behind freedom of religion.

Where women’s rights should prevail, according to Steel, there appears to be less appetite to investigate and prosecute woman’s rights violations within religious organisations. Steel also provides some social commentary around the “problematic” way we raise young men as leaders. But there are some other factors worth considering.

Read more: Why the label 'cult' gets in the way of understanding new religions

Cults and the appeal of ‘family’

Why do ostensibly free individuals join these types of restrictive and often damaging groups, obsessed with female reproduction and sex?

From the 1960s, the contraceptive pill for women (making it easier to choose pregnancy or not), the legalisation of abortion (which has just become complicated in the United States, of course, with the repeal of Roe v Wade) and easier access to divorce have meant new levels of freedom for women. More choice – for men and women – as to what a family might look like has also introduced uncertainty.

During this same period, there’s been a massive increase in fatherlessness and single motherhood. And in the US, 2019 Justice Department figures show 70% of juveniles in state-operated institutions are fatherless. Cults are religiously conservative expressions of a wish to return to the time when sex was a huge deal, because the cost to both men and women was so high – and to return the man to inside the family unit (at any abhorrent cost).

Chuck Palahniuk has lamented that his book is one of only two works of fiction that address contemporary masculine issues and what it means to be a modern-day man (the other being Dead Poets Society). The main characters in Fight Club discuss whether they should get married. Jack says to Tyler, “I can’t get married, I’m a 30-year-old boy”. Tyler responds, “We’re a generation of men raised by women, I’m wondering if another woman is really the answer we need?”

Steel notes cults are a feminist issue – which they undoubtedly are. But women’s issues do not exist in a vacuum. The factors that have led to single-mother houses, with fathers absent, have been pervasive since the 1960s. Generations have experienced fatherlessness. And there’s a phenomenon of dad-deprived boys. So it shouldn’t be surprising cults mimic a family with a male leader.

The characters in Fight Club go on to create Project Mayhem, a cult in which you “do not ask questions”, with the catchphrase “In [cult leader] Tyler we Trust”. Sound familiar? Where Fight Club diverts from reality is that a cult or a terrorist group is never purely nihilistic, like Project Mayhem, a group with the anarchic goal of tearing down society completely and starting again.

Cults and terrorist groups differ in that the former seeks to control themselves and the latter seeks to control themselves and society. There is some overlap, as religious cults often have apocalyptic and doomsday “prophecies” – but they require members to have their own houses in order before the apocalypse, to avoid hellfire.

Do As I Say is a heartbreaking and compelling read for anyone interested in the way in which cults and extreme groups come to be, control and ultimately exploit the very freedoms we enjoy in the West.

Sarah Steel shows how our desire for meaning, love and social connection can have tragic outcomes when misdirected. This book should give us pause to consider how we can put meaning, order, and structure into our own lives without giving into religious lies, conmen and the most restrictive conditional love.

Shane Satterley does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.