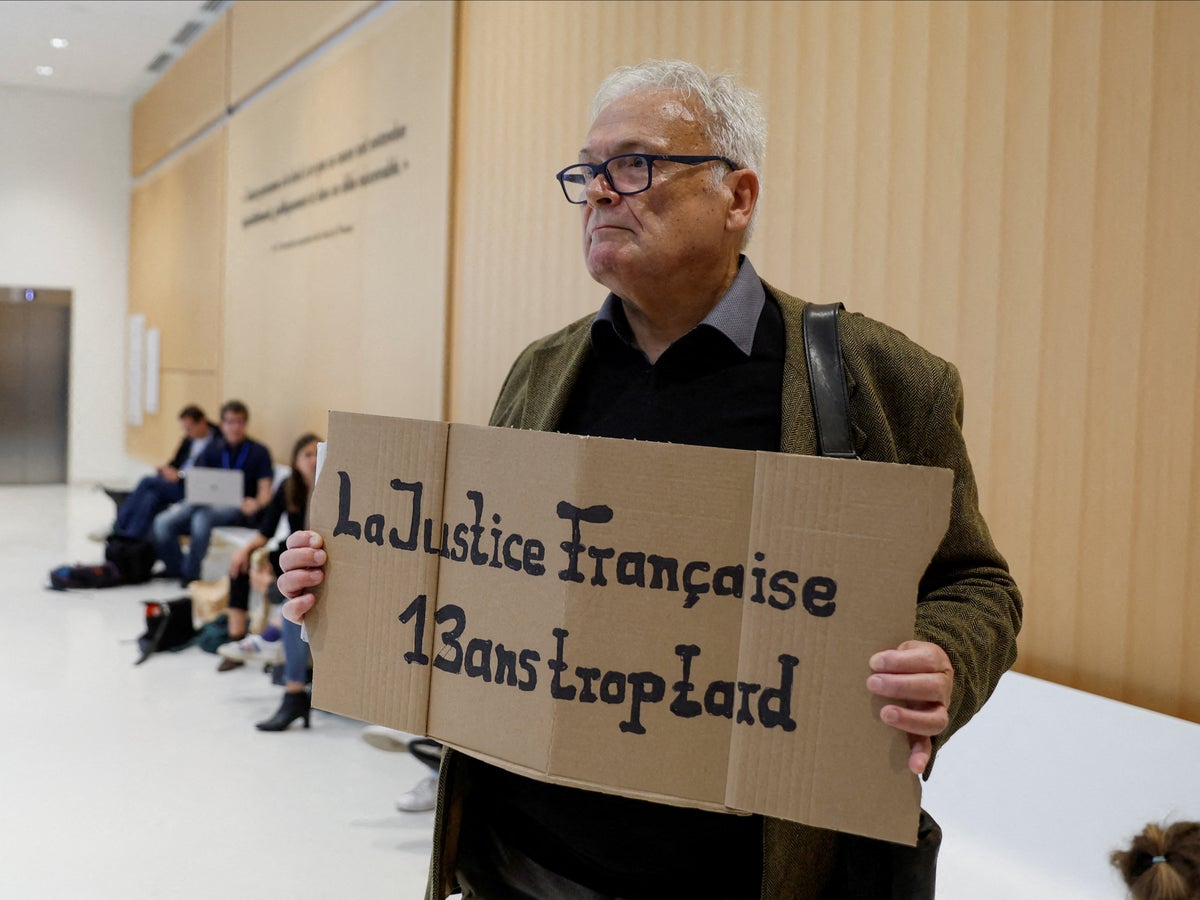

Bereaved relatives of those killed when a passenger plane plunged into the Atlantic Ocean shouted “shame” and “too little, too late” at the executives of Airbus and Air France as a long-awaited trial got under way in Paris.

Both companies pleaded not guilty to involuntary manslaughter over the crash that saw 228 people on board die after Flight AF447 nosedived during an equatorial storm while travelling from Rio de Janeiro to Paris on 1 June 2009.

“Thirteen years we have been waiting for this day and we have prepared for a long time,” Daniele Lamy, whose son died in the crash, said before the nine-week trial opened, while German Bernd Gans – who lost his daughter – called the wait for justice “almost inhuman”.

Emotions ran high and there were some shouts of anger from the loved ones of those killed as the chief executives of Air France and Airbus, Anne Rigail and Guillaume Faury, expressed condolences during their opening statements.

The trial is expected to focus on pilot error, and the icing over of external sensors called pitot tubes.

The A330-200 plane vanished from radar between Brazil and Senegal with 216 passengers and 12 crew members on board, made up of 33 different nationalities.

As a thunderstorm buffeted the plane, ice disabled the pitot tubes, blocking speed and altitude information. The autopilot disconnected and the crew resumed manual piloting, but with erroneous navigation data. The plane went into an aerodynamic stall, its nose pitched upwards, before plunging into the sea.

It took two years and remote submarines to find the plane and its black box recorders on the ocean floor, at depths of more than 13,000ft, which showed that pilots had responded clumsily to the problem with the speed sensors and lurched into a freefall without responding to “stall” alerts.

Preliminary findings have called into question the efforts taken by Air France to ensure pilots were well trained, and there is confusion over how the experienced crew of three failed to understand that their jet had lost lift or “stalled”.

Checking this required a basic manoeuvre of pushing the nose down, as opposed to pulling it up as they did for much of the fatal four-minute plunge towards the Atlantic in a radar dead zone.

Airbus, meanwhile, is accused of knowing that the model of pitot tubes on the aircraft was faulty, and not doing enough to urgently inform airlines or ensure training to mitigate the resulting risk. The model in question – a Thales AA pitot – was subsequently banned and replaced.

The relative roles of pilot or sensor error in the crash will be key to the trial. Bitter divisions between the two well-known French firms have raged behind the scenes for more than a decade over which should be blamed.

Lawyers have warned against allowing this to sideline bereaved relatives during the trial, with attorney Sebastien Busy insisting that “victims must remain at the centre of the debate”. He added: “We don’t want Airbus or Air France to turn this trial into a conference of engineers.”

It is the first time that companies in France have been tried for “involuntary manslaughter” after a plane crash, which was the worst in Air France’s history.

Each company faces potential fines of up to €225,000 (£197,500) if they are convicted – the equivalent of just two minutes of pre-pandemic revenue for Airbus and five minutes of passenger revenue for Air France.

No one risks prison as only the companies are on trial, and victims’ families say individual managers should also be in the dock.

Nevertheless, relatives – who live in countries across the world – place great importance on the trial after a long quest for justice, while aviation industry experts believe lessons could be learnt with the potential to prevent future crashes.

“It’s not the €225,000 that will worry them. It’s their reputations... that’s what’s at stake for [the firms],” said lawyer Alain Jakubowicz.

“For us, it is about something else – the truth ... and ensuring lessons are learned from all these great catastrophes,” he told reporters, adding: “This trial is about restoring a human dimension.”

Air France, which has since changed its training manuals and simulations, said it will demonstrate in court “that it has not committed a criminal fault at the origin of the accident” and plead for acquittal.

Mr Faury, the head of Airbus, told reporters after the hearing that “it will be a difficult trial and we are here to offer compassion” as well as “our contribution to truth and understanding”.