A Tennessee judge on Friday promised to rule quickly on a request for public access to records that detail the treatment of a death row prisoner who cut off his penis while on suicide watch in October.

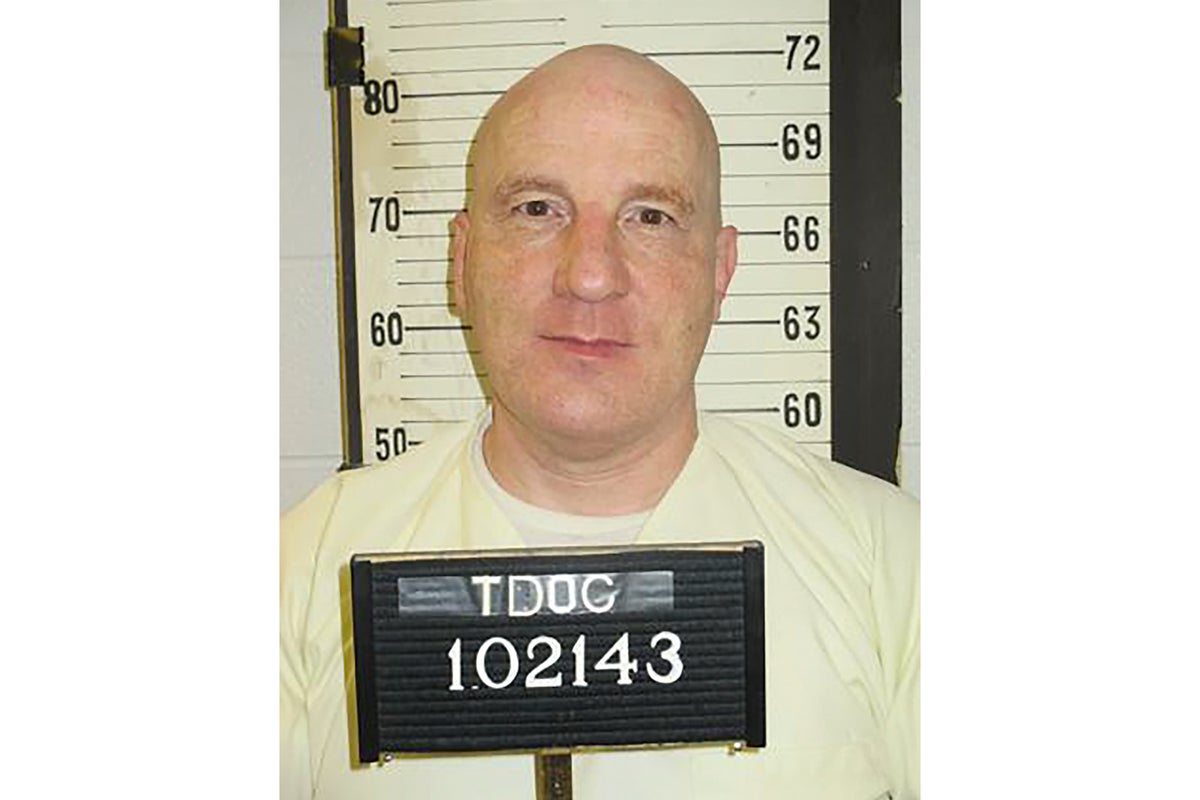

In a lawsuit filed in Chancery Court in Nashville, inmate Henry Hodges accused the state of providing inadequate medical and mental health care.

The inmate, who was sentenced to die for the 1990 killing of a telephone repairman, also accused the state of cruel and unusual punishment for his treatment upon his return to the prison from the hospital. That included keeping him naked and tied down with restraints on a thin vinyl mattress over a concrete slab in a room where the lights were always on and there was no TV or radio.

Hodges was taken to Vanderbilt University Medical Center, where surgeons reattached his penis. After a few weeks in the hospital, he was returned to the prison. Hodges ended up having to return to the hospital to have his penis surgically removed after necrosis set in, according to court filings.

The state has asked for a court order that would protect broad categories of documents from public disclosure, including all video recordings of Hodges’ treatment while inside the prison. The Associated Press and the Nashville Banner are asking for those records to be open.

In court on Friday, Assistant Attorney General Dean Atyia argued that state law exempts certain categories of documents from public disclosure. Those include investigative reports, surveillance video, and other document directly related to the security of the prison.

The state has filed an affidavit by Ernest Lewis, the associate warden of security at the Riverbend Maximum Security Institution, stating that public disclosure of the prison records “could pose a severe security risk to both inmates and staff.”

“We have to protect the public,” Atyia said. "We have to keep prison transportation safe, keep prison officials safe, keep contraband out of the prisons.”

Nashville Banner attorney Daniel Horwitz argued that the state’s assertions of a vague security risk and the single-page affidavit from Lewis are not nearly sufficient to justify keeping the records secret. Officials have to demonstrate specific harm that would come from release of specific documents, rather than broad, conclusory allegations.

“The state has concerns about prisoner transportation?” he said. “Great. Let us know where that is” in the videos.

Hodges' attorney, Kelley Henry, spoke in favor of disclosure, saying that videos of the prison interior are already public on the Tennessee Department of Correction's own YouTube channel.

"By putting it on the internet, that shows it doesn’t compromise safety and security,” she stated.

In addition, the videos refute the state's version of events about Hodges' actions and his treatment by prison officials, she said.

In addition, there is an exception to the statute that protects video and other records deemed to implicate security. They can be released in several cases, including where they show possible criminal activity, said Paul McAdoo, an attorney with the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, who is representing The AP.

Henry, who has seen the videos in question, suggested in court that Hodges' treatment by prison officials could be considered criminal, although she did not go into detail.

No official has been charged with a crime.

Prison security is important, McAdoo argued, but it is up to the judge to review the records the state wants to keep private and determine whether security is likely to be compromised by them.

Hodges has said he wants all the records open to the public, including his medical records. Atyia said they would not oppose the release of the medical records.

A Nashville jury convicted Hodges of murder in 1992 and sentenced him to death for the killing of the repairman, Ronald Bassett. Hodges also was sentenced to 40 years in prison for robbing Bassett.