Researchers worry more than half of global efforts to cut greenhouse gases by using energy more efficiently could be wiped out by a sneaky efficiency paradox called the 'rebound effect'.

In 1865 English economist William Stanley Jevons wrote that efficiencies in industrial production didn’t bring coal consumption down - it increased it. In his book The Coal Question, Jevons argued James Watt’s more efficient steam engine made coal a more cost-effective power source, leading to steam engines being installed in more industrial businesses.

Although the amount of coal used in each engine was less, the total was greater.

These days the Jevons’ Paradox is often called the ‘rebound effect’ - the impact of efficiency measures being the opposite of what is anticipated. And it could potentially have a big impact as governments, companies and individuals try to use energy efficiency to reduce the harmful effects of greenhouse gas emissions and climate change.

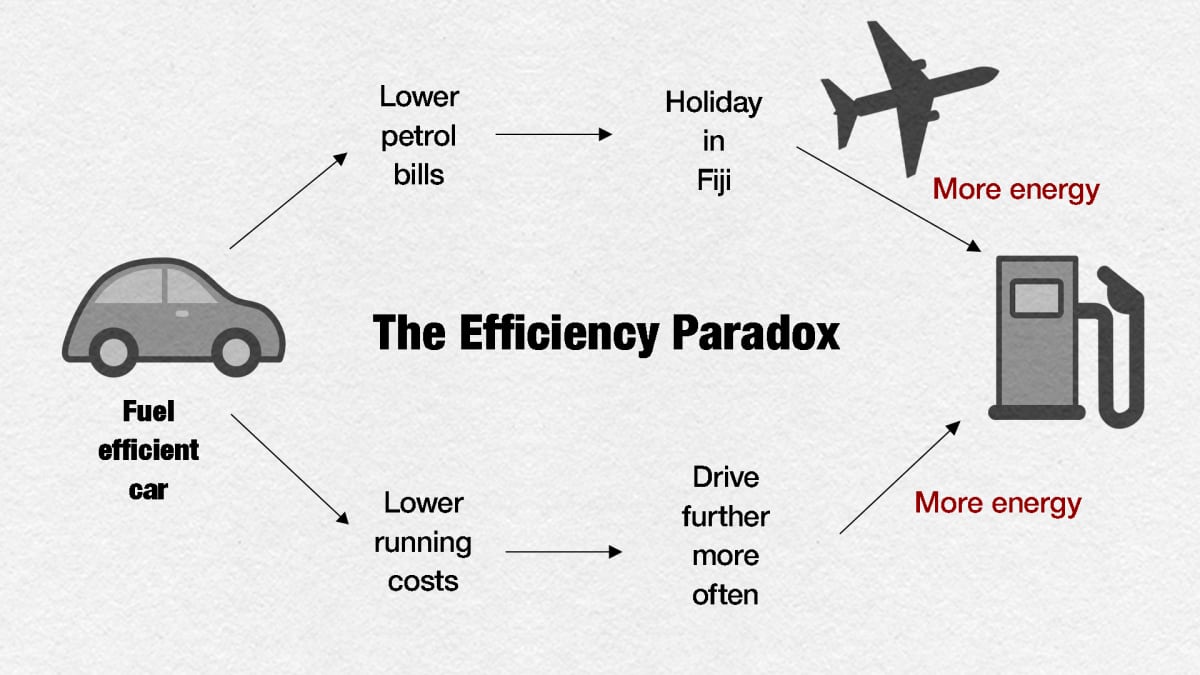

Take the graphic above, using cars as an example. There are the direct impacts of the rebound effect: someone who buys an energy efficient car ends up using just as much fuel because they travel further in said efficient car.

There are also indirect impacts: that same person using the cost savings from their more efficient car to buy other products that produce greenhouse gas - plane tickets, for example, or clothes, or furniture, or more of that unnecessary plastic stuff that fills our homes.

READ MORE: How your home can save the planet Shaw to MBIE: Don’t delay insulation regulations

You can see where the argument is going here. Energy efficiency measures are seen by many, including our own Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority, as a top priority for cutting carbon emissions and reducing warming.

But the rebound effect could mean a big chunk of those reductions are lost.

A paper by a team from the University of Leeds in the UK looked at 33 different studies on the rebound effect and tried to put a number on its impact. They came up with 63 percent. That is, 63 percent of energy savings could be wiped out by the rebound effect.

That puts our climate targets at serious risk of not being met.

Another study focuses specifically on the potential for rebound effects in electricity consumption in New Zealand. The three-person research team - from Australia, Indonesia and Denmark - chose this country because of the high level of renewable electricity here and its importance in our decarbonisation efforts.

The researchers wanted to examine the rebound effects that might hamper our decarbonisation-by-electrification strategy.

That study also puts numbers on the rebound effect.

In the residential sector, the news is good. The rebound effect has “insignificant” impact on residential electricity conservation measures, the study found.

“Energy conservation policies to reduce electricity demand in New Zealand homes may still be effective.”

"Economy-wide rebound effects may erode more than half of the expected energy savings from improved energy efficiency.” Steve Sorrell, University of Sussex

But there is more impact in other sectors. “We find the average values of the rebound effect to be 54 percent and 23 percent for the industrial and commercial sector respectively.” This suggests “most of the expected reduction in electricity use from energy efficiency improvements alone may not be achieved in the industrial and commercial sectors”.

And that matters. “The findings have implications towards energy conservation,” the study authors say. “The results also highlight the danger of ignoring the implications of rebound effects in sectoral electricity demand under the New Zealand Energy Efficiency and Conservation Strategy 2017-2022.”

They were studying New Zealand, but the impacts are global. If the rebound effect does prove to be as big as researchers have found, that means international energy demand will be higher than expected - which isn’t good for the planet. Given that most countries use a higher proportion of fossil fuels in their electricity, that means decarbonisation will be harder than expected.

As Paul Brockway, lead researcher on the University of Leeds study, told the New Scientist magazine: “We’re not saying energy efficiency doesn’t work. What we are saying is rebound needs to be taken more seriously.”

That’s particularly important when it comes to modelling around future energy usage and efficiency. At present, scenarios from some of the leading energy and sustainability agencies around the world (including the International Energy Agency, the UN climate science panel, BP, Shell and Greenpeace) don’t give rebound enough weight, said another co-author, Steve Sorrell at the University of Sussex.

“Global energy scenarios may underestimate the future rate of growth of global energy demand... Economy-wide rebound effects may erode more than half of the expected energy savings from improved energy efficiency.”

Gareth Gretton is senior advisor, evidence, insights and innovation at EECA, the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority. He says the rebound effect is something he and his colleagues have noticed, particularly as part of the Warmer Kiwi Homes insulation programme. Perversely, Gretton sees it as a good thing.

"We have observed over 10 years and after insulating hundreds of thousands of homes that the reduction in energy use is not as big as the theory would tell you. What's happening is people are taking back some of the benefit they are getting from increased energy efficiency, and heating their homes more. And those warmer homes are making people healthier because before, the houses were under-heated."

Gretton says there are still some energy savings coming from the insulated homes, and the wellbeing impact of the rebound effect on people living in the houses is worth the loss of the full efficiency savings.

EECA has less concrete data on the impact of the rebound effect in the industrial and commercial sectors, Gretton says, but he is less pessimistic than others.

"Some people think energy consumption will just go up and up and unless we can decarbonise quickly we will struggle to meet our targets. I believe there are lots of ways the future could look different, and I don't think rebound is inevitable."

He says individuals and companies have choice in their purchasing decisions, including whether or not to use the savings they have made from being more energy efficient in one area on making potentially damaging purchases in another.

EECA is behind the Gen Less website, which encourages businesses and individuals to make climate-friendly choices.

"You have to have in your mind that the [take back and rebound] effects are real," Gretton says. "But you can make purchasing decisions as a consumer that lead to fewer emissions, and it is consumers that drive demand."