I read Andrew McGahan’s Praise (1992) in my first year of university. I was blown away. It was unlike anything else I had ever read: raw, gritty, real.

One of the most prominent writers of Australia’s short-lived literary “grunge” movement, McGahan – along with his peers Christos Tsiolkas, Justine Ettler, Luke Davies, John Birmingham and Linda Jaivin, among others – represented a cohort of young writers interested in a literature that was both political and personal: confessional in terms of their own lives, but also as an expression of a generational experience.

Coinciding with the popular grunge music of the early 1990s, grunge literature was jaded, anti-authoritarian and rage-filled, but retained an element of humour. It described a world of dead-end jobs, empty sex and mind-numbing drugs.

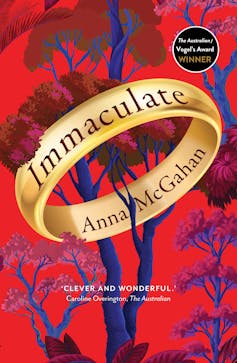

Review: Immaculate – Anna McGahan (Allen & Unwin)

Immaculate is the first novel by McGahan’s niece, Anna McGahan, and this year’s winner of the Vogel Award for writers under 35. The reader looking for the legacy of Andrew McGahan and his grunge roots will find its traces here in the unhoused characters hovering at the margins of the city, frequenting the soup vans where Immaculate’s protagonist, Frances, once worked. They return to the cheap boarding houses dotted throughout Brisbane’s inner-city suburb of New Farm, where much of Praise took place.

Some of the sadness and desperation of Praise thus finds its way into Immaculate. But in Frances herself there is also a sense of grunge grown up, or perhaps grunge aged. She is a woman in emotional turmoil following a nasty divorce, the loss of her conservative Christian faith, the revelation of her own queerness, and the terminal illness of her young daughter Neve.

Frances and her ex-husband, Lucas, had been senior members of a large church in Brisbane called Eternal Fire, where he remains as a pastor. Her faith had formed the foundation of her personal and professional identities, and of their marriage.

Its crumbling has led to the collapse of everything in her life. She is “no longer a wife, […] no longer a mother, fifty per cent of the time”.

Frances divides her time between her part-time duties as mother, in which she maintains a charade of ordinariness for her sick child, and the days when she is not responsible for Neve, when she avoids her home and anyone she might know. She works in dark clothes in the shadows of a theatre each night, before visiting a brothel to receive the regular attention of a sex worker named Celine.

This relationship is not so much about sex or even companionship. It is a charade of domesticity. Celine offers Frances “the paid experience of a familiar, peripheral loneliness”.

Frances’s life is now just an echo of the real, the numbness with which she moves through the world reminiscent of the literary interests of the grunge.

Read more: An unreliable narrator and a stormy relationship propel Stephanie Bishop's moody new novel

Narrative in tatters

Even the structure of the narrative itself is in tatters. Immaculate is formed by epistolary fragments of first-person narration from Frances and her teenage wards, Mary and Jasper, as well as other textual artefacts: text and telephone messages, letters, police records, news reports, websites, and so on.

The first-person sections are styled as biblical passages – The Gospel According to Frances, The Book of Mary, The Book of Jasper – granting these characters an authority they do not possess elsewhere.

Mary is the name adopted by 16-year-old Penelope, who has suffered horrific abuse and is now pregnant and alone. Rather than style herself as a victim, however, Mary insists that her pregnancy is the result of an immaculate conception, and that she has a higher order of business to attend to. Specifically, it is her task to guide guests to otherworldly dinner parties at which they discover fundamental truths about themselves.

Frances and Jasper are two of these guests, as is Celine’s partner Glenda, who is suffering from early Alzheimer’s, and others who frequent a large inner-city park at night.

The narrative mode creates a sense of authenticity and veracity, making readers privy to factual evidence from which they can form their impressions. McGahan has also incorporated the genre of verbatim theatre into the novel. Like epistolary narrative, verbatim theatre aims to bring the authenticity of lived experience to a story.

The play being performed at the theatre where Frances works is itself a verbatim piece, written by Glenda and recording the experiences of those lost souls who gravitate toward the park. As one theatre-goer observes, “they collected interviews from all these people who have experienced profound grief and suffering, and put them into a piece of theatre. All their real words!”

A dreamlike fantasy world

These narrative strategies work alongside the first-person accounts to ground the otherwise unstable or fantastical elements of the novel. This is the other side of Immaculate’s emphasis on the real: a dreamlike, fantasy world, which somehow exists within a shared consciousness of several of the characters.

The magical-realist space offers the characters a way of healing their real-life traumas through a deeper understanding of their individual fears and desires.

Traces of this dream world remain in the real world, making it impossible to write off this part of the story as illusion or hallucination. Like Frances, the reader must accept both experiences as equally real, without succumbing to a spiritual explanation that would negate Frances’ break with the church. Like Frances, the reader must accept the possibility of a miracle, even if it does not look the way she had expected in her former faith.

Some fairy tales, Frances realises, “tell the brutal truth”, while others “give you false hope of happy endings”. Ultimately, the fairy-tale world is a way for Frances, Mary, Glenda, Jasper and others to accept the “brutal truth”. That in itself could constitute a “happy ending” – at least, as happy as an ending can be when it involves the loss of a child.

Frances’s fantastic experiences allow her to see the truth, but as a lesson about the duality of pleasure and suffering in life. Now, she understands, “the miracle is what He has already given me, not what I am waiting on. And there is great healing in that.”

If grunge had one theme at its core, it was to question what was known or accepted, to record and sometimes resist the social expectations that make us numb to our own selves. That theme remains in Immaculate, but McGahan finds a way beyond grunge’s nihilism, even in the depths of the most profound tragedy.

Jessica Gildersleeve does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.