The word "chaplain" is usually associated by most people in the U.S. with a Christian priest or pastor preaching or conducting religious services in a hospital, school, or prison. However, as society becomes more religiously (and irreligiously) diverse, the idea of a professional, secular and non-denominational chaplain is gaining popularity.

Instead of endorsing a specific religion, chaplains provide pastoral care, which involves guidance and emotional or spiritual support to members of the institution they are attached to. By being religiously neutral, these chaplains are able to reach out to as many people as possible, respecting their personal beliefs rather than trying to convert them. This is especially important in healthcare settings, where preaching or proselytizing to people in dire medical situations can be seen as unethical and even predatory.

In the 1920s, Anton T. Boisen pioneered the hospital chaplaincy and clinical pastoral education movements, challenging traditional religious views and proposing that religious experiences and some forms of mental illness could be interconnected.

One of the organizations championing Boisen's more humanistic approach to chaplaincy is the College of Pastoral Supervision and Psychotherapy (CPSP). It focuses on a holistic approach to pastoral care, emphasizing the "Recovery of Soul" and offering comprehensive Clinical Pastoral Training that integrates pastoral care, psychotherapy, and medicine, equipping chaplains with the skills needed for effective emotional and pastoral support.

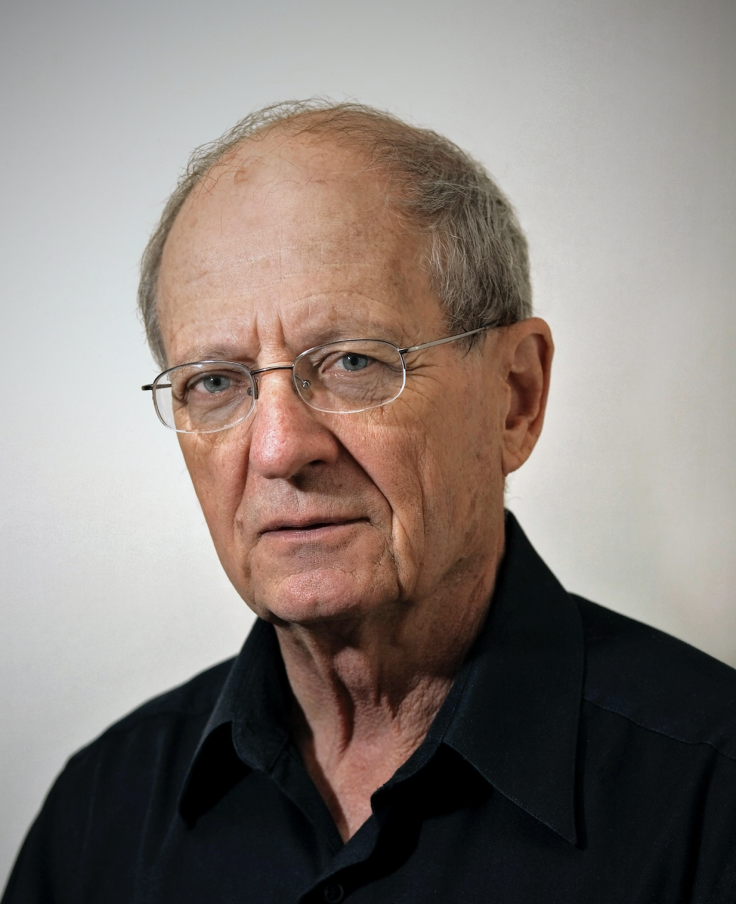

Rev. Dr. Raymond J. Lawrence, along with Rev. Dr. Perry N. Miller, founded CPSP in 1990, and he currently serves as its general secretary and CEO. Lawrence has a long and colorful history in the religious and clinical pastoral spheres, dating back to the 1950s. He is no stranger to controversy, and his empathy and passion for disadvantaged people have led to conflict with authorities multiple times, something that he is proud of.

"I decided I wanted to be a minister when I was 13," Lawrence says. "I was a bleeding heart from my childhood, and I empathize with people who are in trouble, so I went into the ministry. The world is full of underdogs, and I believe it's my mission to focus on them."

After finishing his seminary education, Lawrence first served as a pastor for the Methodist Church for several congregations in rural Virginia.

"I was somewhat an oddball and didn't fit in with the rural congregation," he shares. "Somehow, something turned and they took a liking to me, but the church hierarchy didn't like me, so they decided to move me to another church. That's when I left the Methodist Church and joined the

Anglican Church, which I found more artistic and more sober. Then later, I moved to the Episcopal (Anglican) Church, where I served at two churches for two years each. I got fired both times because I criticized someone or something that I was not allowed to criticize."

Following the end of his parish work, Lawrence underwent clinical pastoral training and became a chaplain, mostly for hospitals but also in prisons. It was during his hospital chaplain work that Lawrence became involved in the case of David Phillip Vetter, also known as the "Bubble Boy". Due to Vetter's severe combined immunodeficiency, he was forced to live in a sterile bubble for all 12 years of his life. Lawrence, who was the hospital chaplain during Vetter's early years, wrote the introduction for the book ''Bursting the Bubble: The Tortured Life and Untimely Death of David Vetter,'' authored by Vetter's psychologist and confidant Mary Ada Murphy. Lawrence also opened the only formal ethics consultation on the Vetter case.

Lawrence is the author of multiple journal articles and research papers on religion, spirituality, and human sexuality. Several of his books include ''Sexual Liberation: The Scandal of Christendom, Recovery of Soul: A History & Memoir of the Clinical Pastoral Movement,'' and ''Harry Stack Sullivan & Anton T. Boisen: Comrades & Revolutionaries in Psychotherapy.''

Lawrence's fervent belief in inclusivity and standing up for the oppressed is reflected in the values of CPSP. The organization strives to be as non-hierarchical as possible, with a strong focus on representation throughout its training programs and leadership, ensuring a holistic approach to pastoral care.

"I place a high value on open, non-hierarchical community – just people caring for each other. It's my wish and dream for the wider society," Lawrence says. "I also hope that CPSP and similar organizations will have a larger impact on the clinical pastoral movement, which is now controlled mainly by prayer warriors and religious evangelists. I believe that anyone can train to become a chaplain, not just the religious and the clergy. A chaplain should not announce their religion in any respect while doing their jobs. They should go in as a fellow human being, providing support, care, and a listening ear regardless of creed or belief."