Wellington has long claimed to be the capital of arts, culture and technology – and now, no longer able to rely on the public sector to underpin its economy, it must make them pay. Jonathan Milne reports.

Opinion: Wellington has been many things. When Iggy Pop visited in 1979, he took advantage of the suited stiffs and squares to film a promo video for his single, "I'm Bored". The city has been Gliding On. It has been Absolutely Positively Wellington. It's been the Windy City. It's been the Creative Capital.

It's questionable whether any of these brands did much for the city's gross domestic product.

But this century, out of its music and arts community, has developed a new identity that is paying dividends. Wellington is the Collab Capital. And it needs it, because some of its more traditional income streams are fast drying up.

READ MORE:

1/ Why does everybody hate Wellington?

2/ Leaders push back against sexist, racist abuse online

3/ Socks, frocks and saving Wellington from self-indulgence

4/ Rates and old mates – bailing out our cash-strapped capital

Collab Capital? Setting aside Iggy Pop's unfortunately memorable collaboration with Radio With Pictures, Roger Gascoigne, Rosie Langley and other local luminaries, the contemporary collab really emerged from the city's dub and roots scene.

The best example is Fly My Pretties, made up of an ever-changing cast of musicians from the Black Seeds, Fat Freddy's Drop, the Phoenix Foundation, Cairo Knife Fight and more. Fly My Pretties' website lists no fewer than 50 collaborators over the past 18 years. And that collab has helped lift associated acts like Fat Freddy's onto the international stage.

Musicians started working with beer brewers. Coffee roasteries started working with ceramics artists. Wellington on a Plate food festival brought crochet artist Chili Philly to town to show off his knitted burgers and berries and kiwifruit. Oh, and last month, games developer PikPok collaborated with Wellington brewery Garage Project to create an exclusive beer to celebrate the 10 year anniversary of hit video game series Into the Dead.

It's a small town. Two of the Garage Project founders previously worked at PikPok. “Garage Project is a great example of what we at PikPok are trying to achieve,” says Mario Wynands, the PikPok chief executive. “Using local talent, a passion for their industry, and the grit and determination to succeed."

[* Whoop, whoop, disclosure! Jonathan Milne's fine dining, craft beer-tasting, flights and electric bus ride from the airport were courtesy of WellingtonNZ, the region's economic development and tourism agency.]

Ben Schott, the author of Schott's Miscellany, argues at Bloomberg that whereas brand partnerships used to be sparing, targeted, special even — we see now a feeding frenzy of collaborative cross-pollination. "As subcultures flourish, no new collaboration is too zany."

There have been undeniably bad collabs, like Whittaker's "Coconut Ice Surprise" pink or blue gender reveal chocolate, in partnership with Plunket.

And there have been good collabs, like the NZ Symphony Orchestra working with producer Jackie Chan on the animated movie Wish Dragon, and with Los Angeles-based game developer Respawn on Titanfall 2.

John Allen, the chief executive of economic development agency WellingtonNZ, reckons there are easily 100 tech firms within a 10 minute walk of each other in the city's CBD, and they feed off each other and the other creatives in the area. "That's the reason they're here, that community and support," he says. "I know to an Aucklander, 100 doesn't sound like a whole lot. I understand. But the truth is, it's driving a huge amount of economic activity of this city."

The likes of Drax Project and the NZSO have been doing a huge amount of recording for video games. These commercial innovations are important – and that's because there's one collab that just isn't turning a dollar anymore.

It's the parasitic partnership between Wellington and central government. There's an argument that central government, even as it built and rented tower buildings and subsidised local arts and businesses, has been sucking the life out of central Wellington.

Much of New Zealand's productive sector learned to stand on its own two feet in the freemarket reforms of the 1980s. But in Wellington, there remained many organisations that were dependent on subsidies and grants and public contracts; those that were finally detoxxing got a new fix in Covid and were hooked again.

|

|

|

Socks, frocks and saving Wellington from self-indulgence Writing at Newsroom, Jonathan Milne described a capital city of politicians and grey bureaucrats that the rest of NZ loves to hate – so Wellington's new mayor flies him down to wine and dine him and persuade him otherwise. • Read more |

|

"You would think of the NZSO as historically being reliant on government funding," Allen says.

"But the work the NZSO has done in the last wee while, driven and partly accelerated by Covid – in developing an international audience through live streaming, in doing a lot more in the recording space for games and screen stuff, in thinking more about Maori and Pacific audiences, in restructuring their concerts so that they're shorter, snappier, they're at 5.30pm to 6.30pm on a Friday night in Shed Six which is a less formal venue than the Michael Fowler Centre – all of that, I think, is indicative of the the recognition in the arts sector that it needs to change."

Fewer, closer businesses

It's a quiet work day when we pop into games company PikPok, upstairs on Willis St.

Many staff are working from home, or from the company's studio in Colombia. Those here are wearing masks; with the latest version of their zombie apocalypse shoot-em-up hit game Into the Dead launching, they can't afford an office Omicron outbreak.

Mario Wynands shows us around. In a sound studio down the corridor, an employee is practising her oboe. Yes, PikPok has done its own musical collaborations, too.

Collaboration is easy in Wellington, he says. Partly, it's how compact the CBD is. If you want to meet someone for coffee, you message and say, 'meet you in 2 mins'.

"It is just so accessible, you know, you're not having to get in a cab or take an Uber for 20 minutes, just to get to the next thing. It creates this smaller sense of community, that people feel more social responsibility or willingness to reach out."

The NielsenIQ Quality of Life Survey shows fewer than one in 10 Wellington respondents have ever owned a business – a lower rate than anywhere else.

But Wynands doesn't see that as a problem. "I came from a family where my parents had their own business."

He and two friends started PikPok in a flat in the Hutt Valley in 1997. They’ve grown it to a company that earns tens of millions of dollars and creates hundreds of jobs. And some of their employees have gone on to start their own successful game companies – or craft breweries!

The Quality of Life Survey also shows that of those 9 percent who have owned companies, some have closed them down over the past two years; of those that remain, they're more likely to have shifted their operations online than in any other city, sucking the lifeblood from the heart of the CBD.

John Allen says the public service, too, actively discouraged workers from going back to the office for quite some time.

And that's a big deal, given how much of the central city is populated by civil servants, or by the consulting and researching and lobbying agencies that rely upon them. Indeed a massive 16.3 percent ($4.5 billion) of Wellington City's GDP was from core government administration, defence and safety agencies in 2001, according to Infometrics.

That means the Wellington economy is four times more reliant on the public sector than the New Zealand average.

Central government contribution to local GDP (%)

There are two potential problems with that. At least, as I explore the Wellington economy, that's my starter-for-ten theory.

First, it may tie the city's hands. It's harder for civic leaders to create a tech innovative economy – the "city of impact" that new mayor Tory Whanau describes – when those small-to-medium-sized creatives and innovators are pushed to the physical and cultural fringes by the machinery of big government.

In an interview, I put this to Whanau: You can't say, we're going to turn Molesworth St into the tech precinct and we're going to turn The Terrace into the arts precinct, because you're constrained by this monster that is government, aren't you?

"No," she laughs, bemused. "I don't think so. And if that's what we wanted, we could turn it into that – but we don't want to."

"It's coming to that crucial point where we do need it. And we've heard from a lot of rural areas that they're doing okay. They have a lower level of need than the capital city and Auckland." – Tory Whanau, Wellington mayor

The second potential problem, then: When the money dries up, there are a whole lot of organisations in trouble. And history shows that while Labour-led governments may bulk up the Wellington public service, National-led governments cut it back again.

Has government spending become a crutch for Wellington? "I can't lie, they're a massive contributor to our local economy."

"And they they form quite a big part of our culture – they do! But that's a positive thing. The city could stand on its own two feet without a city government. But that's not something I'd want to see. I think government and Parliament are a really positive part of our culture."

Paying for the road cones

So, Wellington's leaders like the vigour the civil service brings to the city. Thirty thousand public servants buy a lot of flat whites. The problem is, they don't think the Government is contributing its share towards the infrastructure.

Tory Whanau and John Allen think Wellington is being short-changed by central government. "In the longer term, we need to make this place affordable, so that every industry can work here," Whanau says. "The biggest feedback that we've had from various industries is effective public transport, affordable housing, and access to stuff – those are the key priorities of Council.

"There are probably cases where certain industries have become overly reliant on support. And there are certainly times where government needs to step in." – Mario Wynands, PikPok

"And I think as long as council itself and me are good at telling the story – it's going to be a city of cones for a while but cones are markers of progress – then we will become the city of impact. It's just going to take some time. And it's going to take some investment. We've needed it for some time, but it's going to happen now. And that's okay."

There are three respects in which Wellingtonians feel cash-strapped. First, the cost of living is rising for families and households. The NielsenIQ Quality of Life Survey shows Wellingtonians are finding their housing costs among the least affordable in the country, and they are frustrated with the lack of amenities – for instance, the city's central library is closed for at least seven years for earthquake strengthening work.

Secondly, businesses like PikPok say their straitened by a lack of government support – Wynands has been lobbying Government for tax breaks like those the Australian Government has offered its gaming industry.

But do they want to lean so heavily on government subsidies? "Now we're getting into an interesting debate! I think it depends. One of the challenges of government is that it generally moves quite slowly. And the commercial landscape can change incredibly quickly.

"There are probably cases where certain industries have become overly reliant on support. And there are certainly times where government needs to step in, in order to resolve an issue or an opportunity or to help the response from the commercial side."

"It is expected that the costs of our services and projects will increase beyond those forecast in our plans, with consequential decisions being required about their affordability and about the Council’s financial limits." – Wellington City Council

The third respect in which Wellington is (indisputably) cash-strapped is in its local governance. Council officers led by chief executive Barbara McKerrow published the obligatory pre-election report, last year, and it's gruelling reading.

At a time when the council is planning to cram 30 years of infrastructure work into 10 years, there's a shortage of operational funding and investment capital. Traditional sources of non-rates revenue are declining or becoming less secure, the report says.

For instance, as the city grows and rebalance its streets and transport network, it will provide less on-street parking – so the $42 million it earns from parking will shrink. The $13m dividend from it stake in Wellington International Airport stopped in Covid, and is anticipated to take time to recover. And it faces the loss of all its water and waste water revenues, if the Government's Three Waters reforms proceed next year.

At the same time, high inflation is causing its costs to blow out, at the same time that its insurance premiums are soaring, as insurers better understand the risk of earthquakes and other adverse natural events. It can't maintain the same levels of cover – so the council is going to have to cut its cover and take on greater risk.

"The Government has been prioritising funding provincial over urban centres, despite facing challenges such as higher rent and a working population that has changed its habits – especially in Wellington where many people clock into central government ministries for their pay cheque." – John Allen, WellingtonNZ

"It is expected that the costs of our services and projects will increase beyond those forecast in our plans, with consequential decisions being required about their affordability and about the Council’s financial limits," the report says.

Over at WellingtonNZ, John Allen is saying the same thing. "Governments around the globe see their capital city as a showcase for what the country can do, and invest money into the infrastructure accordingly. Our city thrives, but that’s on our own merit," he argues.

Much of the cost of the Parliament protests fell on the city, its council and its business community, he argues. Ratepayers fund infrastructure to support Parliament and its democratic decision-making; they also fund the infrastructure to support people who exercise their rights to protest.

Wellington is only half the size of Christchurch, but its ratepayers must support a commuter population that swells significantly during the workdays, because so many people from the surrounding cities and districts work in Wellington. "We punch above what a city of 200,000 usually offers – but people forget that’s what we are."

Wellington is grappling with many of the same problems other places are too, such as outdated water systems, public transport, public buildings that are not up to earthquake standards, recovering from Covid, increasing inflation and a rapidly decreasing property market.

"The Government has been prioritising funding provincial over urban centres, despite facing challenges such as higher rent and a working population that has changed its habits – especially in Wellington where many people clock into central government ministries for their pay cheque, which were actively discouraged for quite some time to go back to the office, but continue their work from home slog."

To be fair, incoming councils all over the country have been grappling with big holes in their budgets – but in the capital, they're looking unhappily at how little they get in government grants and subsidies compared to other councils. Neither does central government pay rates on the valuable property it owns around Parliament, the Molesworth and Terrace precincts, and along the Golden Mile.

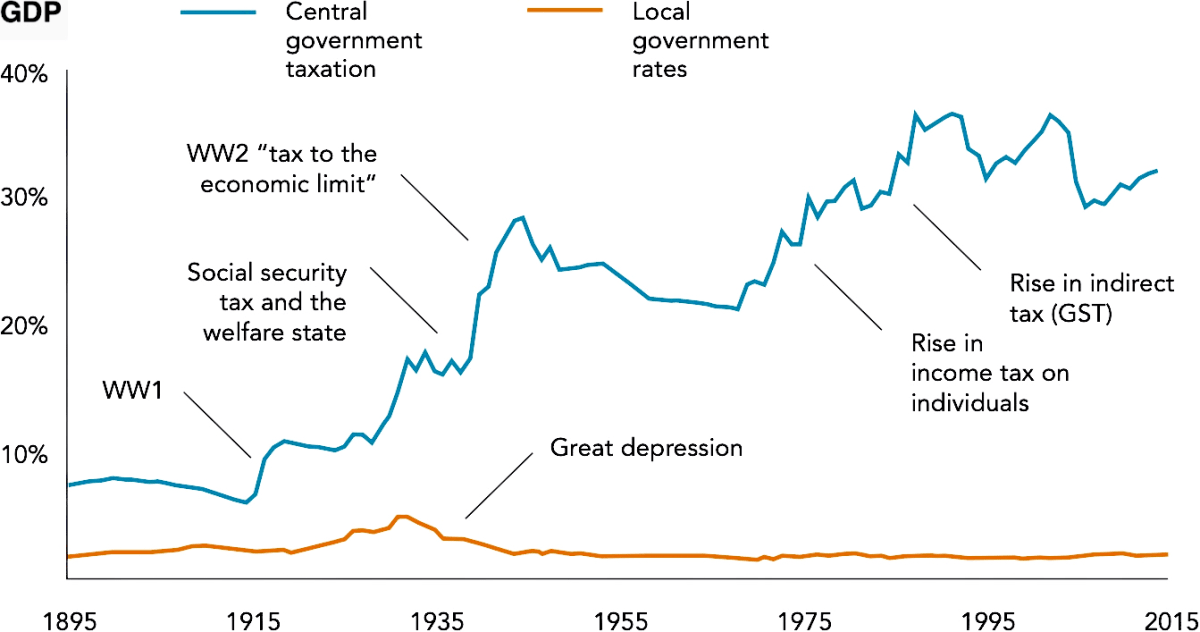

Taxation as a percentage of GDP

The Government-commissioned Future for Local Government Review delivered its draft report late last year. It found that local government was under pressure for funding, capacity and capability. The relationship with central government was characterised by misunderstanding and mistrust and needed significant work.

It "strongly recommends" the law be rewritten to require central government to pay rates on schools, hospitals, conservation estate – and by extension, central Wellington office blocks.

"We'd have to dig into that one," Whanau muses. "Yeah, it's interesting. That is worth a conversation."

Regional New Zealand has had its turn and is doing okay, Whanau argues – now it's time for investment in the big cities. "Why I say we should be the priority is because we've had a level of under-investment for a while now. It's coming to that crucial point where we do need it. And we've heard from a lot of rural areas that they're doing okay. They have a lower level of need than the capital city and Auckland."

Government grants/subsidies contribution to council revenues (per capita)

"I would have expected we could get more, being the capital city that houses central government. That's a huge part of the reason I ran for mayor. I can build relationships across the political divide. it is up to the mayor to really lobby hard on behalf of the city and get those deals."

She cites Housing Minister Megan Woods' announcement that the Government will buy a big block of land on Adelaide Road, near the Basin Reserve on the Let's Get Wellington Moving route. "This will impact our housing and high density plan and therefore, our city. So that's exactly this sort of stuff that we should be getting," she says.

"And that's something that is a priority for me is getting that extra support from the central government, which benefits their workers and the capital city, and therefore central governments as well."

READ MORE:

1/ Why does everybody hate Wellington?

2/ Leaders push back against sexist, racist abuse online

3/ Socks, frocks and saving Wellington from self-indulgence

4/ Rates and old mates – bailing out our cash-strapped capital

► Jonathan Milne visited courtesy of WellingtonNZ, the region's economic development and tourism agency.