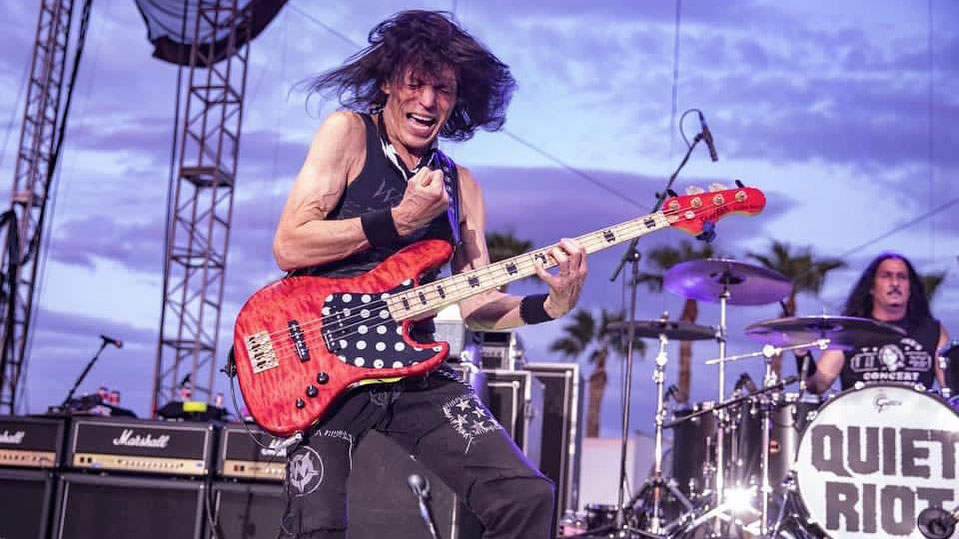

Rudy Sarzo is a hero of no fewer than six decades of bass guitar. In the 1960s, as a Cuban refugee living variously in New Jersey and Florida, he plucked the bass in garage-rock bands. In the ‘70s, he made his bones with Quiet Riot, pioneers of Hollywood's hair-metal scene. Catapulted to fame in Ozzy Osbourne's band in the ‘80s, courtesy of a recommendation from his erstwhile Quiet Riot colleague Randy Rhoads, Sarzo toured the planet with bands such as Whitesnake.

By the mid-‘90s he was a classic rock bassist who commanded enormous respect, laying down lines with Yngwie Malmsteen, Dio and Blue Oyster Cult in the decade that followed. In recent years Sarzo has also trodden the boards with Geoff Tate's version of Queensryche, Animetal, and the Guess Who.

He's a bassist with much wisdom to impart, and where better to share it? Read on as he talks essential gear, professional attitudes, dealing with the still-shocking tragedy of Rhoads' death in a plane crash in 1982, and the skills you need to take the big sounds to the big stages...

The late '70s in Hollywood sound like an amazing era.

“Back then, if you were from the Sunset Strip, you weren't really labelled as a metal band. You were just a rock band – hard rock, like Van Halen. By the time that I joined Quiet Riot in '78, we were going through the rock versus new wave and punk period. As I learned when I joined Ozzy and started spending time in England. Bands like Iron Maiden, Saxon, Motörhead, and so on were already making their statement in the late '70s in England, whereas that was not really the case in Los Angeles.”

What were the basses you were playing back then?

“Washburn and Music Man, and I also carried with me a practice bass, which happened to be a Roland GR. You remember the first Roland synthesiser bass? You could actually go through a big synthesiser, or you could go out analogue and use the pickup.”

What happened to that really cool black-and-white Washburn you had?

“It's somewhere in Japan. I sold it to a Japanese collector back in the '90s. I look back and I think I should have kept it, but we entered the grunge period in the '90s and that was not a grunge bass, if you know what I mean. It had a certain tone, with original Bill Bartolini handwired pickups. Bill used to wire everything for me personally, so it's definitely a collectable. Actually, I used that bass on Speak Of The Devil, Ozzy's re-recordings of Black Sabbath songs.”

I always wondered how you approached Geezer Butler's bass parts on those Sabbath songs. Did you deliver them as they were originally, or did you add your own spin?

“I played exactly what was on the records, which was very challenging because there were a lot of really cool riffs that are very exclusive. It's a very original style of bass playing, very stylised, so when I played on the record I was just trying to do justice to Geezer's blueprint of what the song is.”

What kind of guy was Randy Rhoads?

“If it wasn't for Randy, I would have never had the career that I've had, because he trusted me. This was the scenario: Ozzy was about 10 days away from going on the road, and they were in Los Angeles looking for a bass player. Not only a person that could play those songs, because there were many qualified musicians who could do that, but they needed somebody they could trust.

“I had already worked with Randy in Quiet Riot, so he told Sharon, ‘Listen, Rudy is the perfect guy because he's not going to be a bad influence on Ozzy. He looks good, he's reliable, and he's going to be somebody to hang with on the bus!’”

Randy knew you well, of course.

“He trusted me. He put his reputation with Sharon and Ozzy on the line to bring me in. That's how I got in, because I had no track record. And then, in addition, I am a thousand percent convinced that Randy saved everybody in Ozzy's tourbus, keeping the plane from crashing into us. It clipped the bus, but it did not crash directly into the bus, and if that had happened, we would all have perished along with Randy and the others in the plane.”

Jumping from one massive band to another, did you just slot right in with Whitesnake when you joined them in '87?

“One of the blessings in my career is that I get to play with musicians and bands that I am a fan of. That's very rare, especially for some kid from Miami. At the time I wasn't an American citizen yet. I was just an immigrant, a permanent resident, basically – a Cuban refugee that became an American citizen. So for me to go and play with Ozzy and with Tommy Aldridge, whose playing I loved in Black Oak Arkansas, and Randy in Quiet Riot... it was incredible.

”Now, one of the bands that supported Quiet Riot on the 1984 Condition Critical tour was Whitesnake. That's how I got to know David Coverdale and Neil Murray, and of course John Sykes and Cozy Powell. I recalled the last night of the tour, as we were saying our goodbyes, David said, ‘Someday we're going to play together!’ I had already given notice to Quiet Riot that it was going to be my last tour with the band. So I was wondering, ‘How does David know that I'm leaving?’”

”As soon as I finished my commitment with Quiet Riot and was a free agent, I got a call from Whitesnake's management, and we met. David and John were working in the south of France, writing the new record, and Tommy and I went into the office. I was witness to internal conflict within Whitesnake during that tour, and I thought that it would not be wise for me to leave one situation for another situation, so I passed on the opportunity to make a record.

”A couple of years later, in '87, when David was ready for the 1987 record to be released and for the tour to start, I got the call to do the Still Of The Night video, along with Vivian Campbell and Adrian Vandenberg. So we all met at that video shoot and it was instant chemistry. We were like, ‘Oh wow, if you're doing this, I guess I'm doing this too.’ The chemistry was right and it just felt perfect. It was a great combination of people.”

You had a bass back then that I absolutely loved, an Aria Pro II.

“Yeah, it was a custom. I asked them to put Alembic pickups in some of them and Bartolinis in others. I really had to reshape my tone for Whitesnake, because it was the first time I ever played with two guitar players. Vivian was on my side of the stage, and his sound at the time was huge. It almost went into my bass frequency, so I had to really change my tone.”

You played Peavey basses for a long time.

“I was with Peavey up until Mike Powers, the master luthier that I worked with for so many years, passed away in 2013, but I'm very proud of that Peavey. It's gotten so many great reviews, all five-star reviews. When I first sat down with them to design the bass, I was thinking about my first real working bass, a Jazz that I bought in ‘67 for maybe $300 or $400.”

Are you equally happy with five strings as well as four?

“I play four, I play five, and I also play six. They're all tools for the job, you know. I mean, you can't show up for a job with just a Phillips screwdriver.”

What was your first bass?

“My first original four-string was a Kingston bass. I sold it to a kid in Miami and then I bought a Gibson EB. Mine was just a single pickup model with volume and tone. It was headstock-heavy, so I got rid of it. My next bass was a Rickenbacker.”

What advice can you give kids buying their first bass?

“I do these events called Rock and Roll Fantasy Camps, and we get a lot of beginners. They come to me with their instruments and say, ‘Can you tune my bass?’ So I wind up tweaking their basses, spending about half an hour fixing it for them. Then I talk to their parents and I say, ‘I know that you don't know if your son or daughter is going to stick with playing this instrument, but try to give them something that inspires them to get up every morning and want to improve and learn. That's the most important thing.‘”

Any other tips for readers who would like to make a career as a bass player?

“I would say that the key element to a sustained career would be trust. That is something that you can only build by experience, from gig to gig. Be the first guy that everybody's going to call because they know that you're going to be professional, you're going to learn the songs, and you're going to add something to the band that would help them get to the next level. And I'm just being superficial here; I'm not even getting in deep, because I can spend hours talking about the importance of this.

“The other important thing is to learn. It's always about improving. A musician never stops learning and progressing. And never set limitations. I've come to the realisation that I'm never going to be the bass player that I aspire to be, because I really don't want to do that. I never want to get to the point that I say, ‘Okay, I'm done. I've learned everything.‘ There's always more to learn.”

A lot of musicians think of music as a job, but of course it's bigger than that.

“It is way bigger than that. I think I can say this for every musician: we were fans before we were professional musicians. And we must always remain fans of music, of what we do, of the bands that we play with, and of the legacy of the bands. At the end of the day, the audience comes to watch our show to reconnect with a certain moment in time, and we bring that joy to them again. It's a celebration, what we do on stage.”

Are you still improving as a bass player?

“Oh my God, yeah – which is a problem, because I hear my old recordings and I go, ‘I wish I could re-record this now!‘ It's a journey, though. I play more bass now than I ever have. The bass is always in my hands. When I'm on tour, it sleeps next to me, in bed – because I keep playing until I'm too tired to play, then I just lay it down next to me, and then I wake up in the morning and pick it up again.”