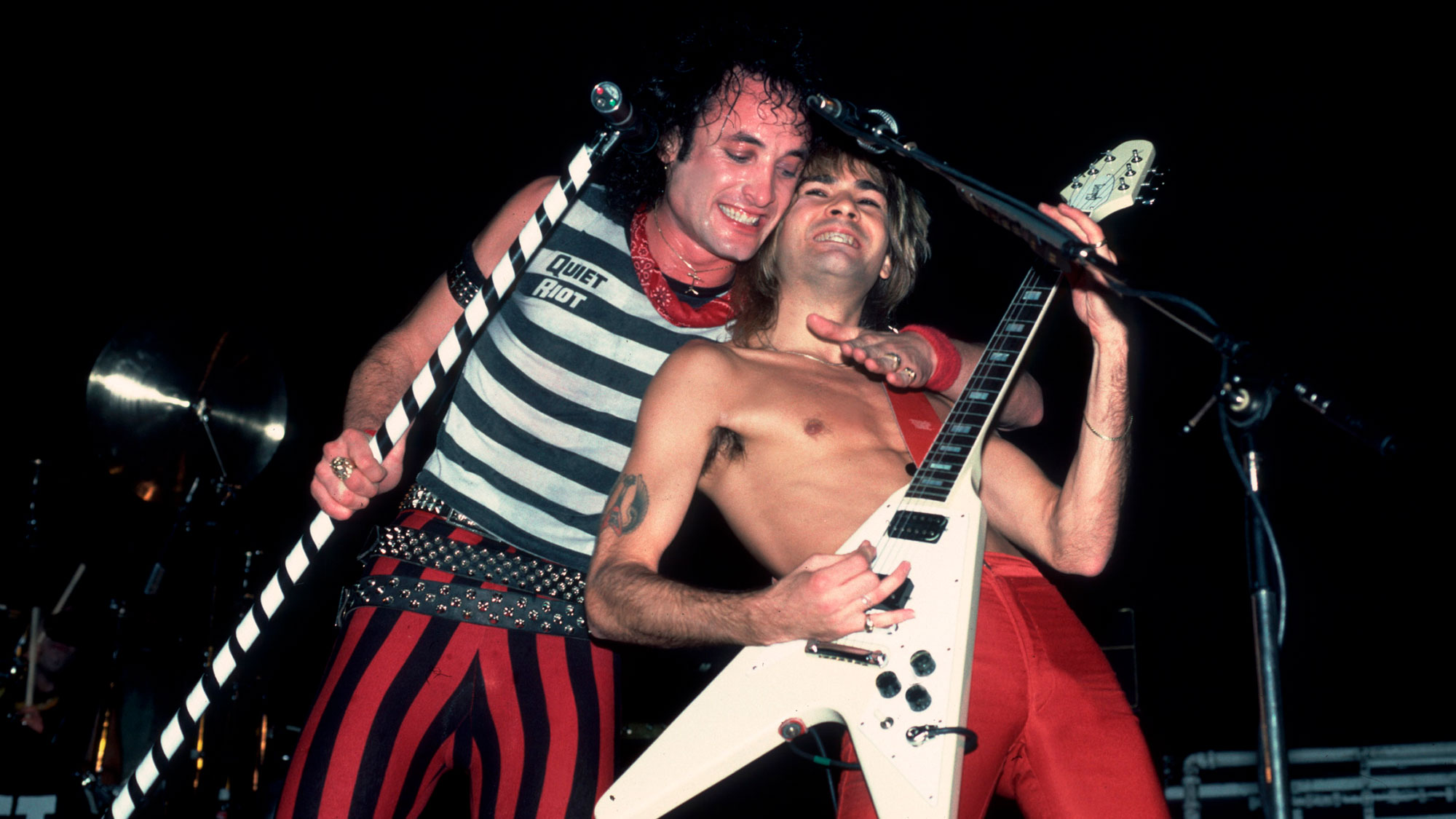

As one of the early comers to the buzzing hair metal scene, Carlos Cavazo assumed the role of lead guitarist for a reformed Quiet Riot, setting off a chain reaction of glammed-out excess.

Stepping out of the shadow of Randy Rhoads and into the spotlight, Cavazo – like many of his contemporaries would do later – infused classical and flamenco touches to Quiet Riot’s mix. The result was a torrent of madness on the backside of Quiet Riot’s 1983 smash success, Metal Health, skyrocketing the unassuming six-stringer.

“A lot of people ask me if I had any idea that Metal Health would be as big as it was,” Cavazo says. “People assume I knew we had this winner on our hands, but honestly, I didn’t. I’m still somewhat shocked that people love it.”

Quiet Riot laid the blueprint for ’80s glam excess, and Cavazo agrees. “I’ve heard people say that we kicked it off, and yeah, we probably did. We were there initially and played a huge role.

“But there were some other bands before us, like Van Halen and Def Leppard. Still, I think Quiet Riot pushed it over the edge,” Cavazo says. “I didn’t think of it back then; we were just doing what we normally would, but looking back, I would agree.”

Quiet Riot’s post-Rhoads era got off to a hot start, but dysfunction undermined them. By the time the ’90s rolled around, Cavazo had departed for a spot alongside Warren DeMartini in Ratt.

“I loved sharing space with Warren,” Cavazo says. “Our styles worked well together, and our songwriting and influences were similar. I’m probably more of a speedy player, while Warren is a more methodical, thought-out kind of guy. Those differing styles gave us fresh textures.”

Things with Ratt fell apart, too. But Cavazo is at peace, having left the dysfunction behind. After laying low for years, Cavazo joined King Kobra and recorded an album in 2023’s We Are Warriors. Things are calmer now, the expectations are lower and the pressures of personality disorders are in the past. But considering his hired-gun status, one wonders if Cavazo will stick around.

“I think so,” he says. “I’d keep working with King Kobra. The biggest thing is their egos aren’t out of control. They’re not ‘problem’ people, and they don’t make life harder. That goes a long way. But it depends on how well accepted we are. King Kobra have been around for a long time, but this is a new lineup. You never know how people will react.”

What sparked your interest in the guitar?

“Two words: the Beatles. When they came out with [1964’s] A Hard Day’s Night, my dad got me and my brother that record. I was only eight. We were really knocked out by it. I just loved the music they were playing, what they did and all the adventures they seemed to have. I knew I wanted to do that, somehow, some way. The Beatles are what led me to where I am now.”

How did Snow, your pre-Quiet Riot band, get together?

I just loved the music the Beatles were playing, what they did and all the adventures they seemed to have. I knew I wanted to do that, somehow, some way

“Snow formed around 1976. It went through a bunch of lineups, and several members filtered out before we ended up with Doug Ellison on vocals and Stephen Quadros on drums, along with my brother Tony and me.

“By 1977, we had that lineup set, and that’s when we started playing around the Hollywood scene and making a name for ourselves. Then, around 1978, we started playing original music, which was the first time I was involved in something like that. Before that, we mostly played covers, so writing my own music was an education.

“We achieved some pretty good success in the L.A. area and were happy with that when it ended. We didn’t get a record deal, but we did manage to do a self-titled EP, which we were proud of.”

What were your main takeaways from that experience?

“Honestly, with the EP, I probably evolved more as a writer. The original version of Metal Health was on that Snow EP, but it was called No More Booze. Me and my brother originally wrote the song, and later on, when I was in Quiet Riot, Kevin [DuBrow] loved it when he heard it, leading to us redoing it on Metal Health.

“The music, lyrics and melodies were changed, but the roots of it came from the Snow EP. So, if anything, I became a better songwriter through being part of Snow. I learned a lot about the business side of things, how things worked and what it took to make it on the L.A. club scene.”

What led you to join a reformed Quiet Riot?

“Snow had just broken up, and we were moving all our shit out of our house, trying to figure out what to do. As that was happening, out of nowhere, I got a call from Kevin, and he said, 'Hey, man, we’re looking for a new guitar player for Quiet Riot. Would you be interested?' I thought about it for a second and said, 'Sure. I can come down and see about it.'

“I went down, met the guys and rehearsed six or seven songs, eventually morphing into tracks appearing on Metal Health. The chemistry was cool immediately, and things between us were great early on. Things changed, but in those early days, everything was great.”

Did you feel pressure to match what Randy Rhoads had done?

People have to remember that at the time, Randy’s work with Quiet Riot was pretty unknown. As far as I was concerned, I only knew Randy as the guitar player for Ozzy

“I was definitely comfortable doing what I did best. People have to remember that at the time, Randy’s work with Quiet Riot was pretty unknown. As far as I was concerned, I only knew Randy as the guitar player for Ozzy [Osbourne]. So I never felt any pressure to be or play like Randy; I felt comfortable doing what I had been doing on the club scene with Snow.

“It seemed to work, and I think my not being influenced by Randy was good for the band and the record. But you know, in a way, Randy indirectly got me the gig; apparently, Randy was the one who told Kevin, 'Hey, you should check out this guy Carlos. A lot of my students are talking about him and saying he’s really good. Give him a call for Quiet Riot.' Kevin got a hold of me through that grapevine. Thanks, Randy!”

What are your memories of putting Metal Health together?

“I remember working on a lot of different stuff early on. We had a lot of material; it took time to get it all together and make it what it is now. Before the album came out in ’83, we recorded a lot of stuff. We had a lot of battles with Spencer Proffer, the producer, about the album’s direction. He’s the one who wanted us to record [Slade’s] Cum on Feel the Noize because he thought Kevin had a similar voice to Noddy Holder.

“That song became a big hit, but we were very against it early on. We didn’t want any cover tunes on Metal Health, so that was a huge battle. But Spencer’s idea was obviously a good one, considering it became such a big hit. Who knows what the record would have done without that song in the charts?”

How about the solo for Metal Health?

“After we reworked the Snow song No More Booze and the lyrics and melodies worked out, I tackled the solo. I used Marshall amps and a combination of Jackson, Charvel and Gibson guitars. I think I used my Flying V for most of it. I probably wasn’t the greatest guitar player back then. I was comfortable playing live, but being good in the studio is a whole different game than being good live.

“Now I had to try and do what I was used to doing on stage in a studio, which was hard because there was no crowd to inspire me. It took a lot of takes, but I did the best I could with it. As a guitar player, I feel you need a good producer to help get the best out of you, which Spencer did with me. It wasn’t one inspired moment but a lot of hard work and collaboration with Spencer.”

Why did Quiet Riot falter after Metal Health?

“That was the high point, and it was a lot of pressure to keep up with Metal Health. But I don’t think it was the band’s fault; our producers and record label always tried to push us in certain directions that didn’t make sense. For instance, the QR III record [1986] had many songs that weren’t metal at all. We should have stuck to our guns and stayed true to what we were about.

“If we had, we could have come up with way better songs than what ended up on that album. And it wasn’t for lack of trying; we’d submit songs, and they’d say, 'No, we don’t like those. Go back to the drawing board and write some more.' They were always trying to push us into a more radio-friendly space, and that was never the type of band Quiet Riot was.”

Was it challenging to stay relevant?

You can be a poor guitar player but a great songwriter, make great money and have a great career. You could also be a great guitar player without a career because you can’t write songs

“Oh, it definitely was. There was such a groundswell of incredible players, and you had to always stay on top of things. The good thing was that I read music, so I was constantly learning licks from books. I liked to read music and always wanted to improve my playing. I play classical, flamenco, Spanish guitar and stuff like that, adding a new flavor. It was a time when you had to constantly try to improve yourself.

“At the same time, you had to keep your songwriting good, too, because a lot of it is songwriting. The truth is you can be a poor guitar player but a great songwriter, make great money and have a great career. You could also be a great guitar player without a career because you can’t write songs. I found that the important thing was to find a balance between both. I worked to be a great guitar player and songwriter, which is very hard.”

Did interjecting classical and flamenco touches help?

“I hoped it would set me apart from a lot of people. But I think a lot of the guys from that era, like Randy Rhoads, Yngwie Malmsteen and even Eddie Van Halen, were classically trained to some degree. That style of music started to wash over the entire era in the ’80s; it was everywhere.

”Still, I always tried to interject classical and Spanish-flavored things into my playing whenever possible. I’d go with it if I felt it fit well with the song. It had to fit the mood, but some songs lend themselves to that, which is good because I was so influenced by them.”

Did being labeled a “shredder” bother you?

If you were a good shredder, it was a good idea to go for it and shred; it could be what got you a career

“No, because I feel any label can be a good thing. The way I look at it is if they’re acknowledging you, you must be doing something noteworthy. But I couldn’t control any of that; I just tried to focus on improving.

”I had good and bad points and worked to highlight the good ones and fix the bad ones. Plus, if you were a good shredder, it was a good idea to go for it and shred; it could be what got you a career.

”As a guitar player, you must focus on doing what you’re good at and highlighting that. So if someone wanted to give the label of 'shredder' or 'melodic guitar player', that’s not something that ever bothered me. I’d happily accept it.”

Do you have any regrets from your time with Quiet Riot?

“Just the way the band basically fell apart. We were up there with Def Leppard, Mötley Crüe and Bon Jovi, but we dropped off the face of the Earth because of certain behaviors by certain members of the band, leading to our demise. I wish there was 'celebrity control' back then to help people with bad behavior problems. I don’t want to mention any names or specific people; I think everyone knows who I’m talking about.”

Was Quiet Riot a case of missed opportunity?

“That band was definitely a missed opportunity. We could have done much more, like, way more, and it’s unfortunate. I was one of the primary songwriters in Quiet Riot, and it got to the point where I didn’t want to bring my best ideas to the table anymore because any idea I brought into the band would be ripped apart and end up being something I never intended it to be. I started holding back my best songs and saving them.

It was more fun playing with Ratt than playing with Quiet Riot. I know the guys in Ratt have their set of problems, but they have a whole different set of problems from Quiet Riot

“What ended up happening was, when I joined Ratt, a lot of the songs I held back from Quiet Riot ended up being on Ratt’s Infestation [2010]. I brought them to the guys in Ratt, and they didn’t rip it apart at all; they loved my songs. It was great, like a whole different thing. At least, that’s how it was at first. There are some personality problems in Ratt, but the ones in Quiet Riot were worse and screwed things up badly.”

How did you end up in Ratt?

“I got a call from Warren [DeMartini]; he left a message. I missed the call, and when I saw it was Warren, I was like, 'Oh, what does he want? There must be some big party he wants to invite me to.' But when I called him back, he told me Ratt was looking for another guitar player and was wondering if I’d want to come down and hang out with them. I went down, rehearsed and checked it out.

“Things felt good between us, and it ended up working out. I brought some songs, they had some songs, and we recorded Infestation. I liked working with those guys, and honestly, it was more fun playing with Ratt than playing with Quiet Riot. I know the guys in Ratt have their set of problems, but they have a whole different set of problems from Quiet Riot.”

So why join Ratt if they also were dysfunctional?

“Yes, they were and are dysfunctional, and I’m sure Ratt will never happen again because of everything that has gone on. There’s too much water under that bridge, and I guess too many bad things happened. But you know, Ratt’s dysfunction isn’t so much about ego; it’s more business-related. Whereas Quiet Riot is all ego-driven stuff. There was a lot of one-upmanship, betrayal and dark stuff that happened within that bad.

“So in that way, Ratt is very different. They had their own differences with each other because they’ve been together longer, but I got along with each of the guys in Ratt. But without going into too much detail, things within Ratt were definitely weird.”

What would you say was the final nail in the coffin?

There’s too much water under that bridge. I got along with the guys, but… without going into too much detail, things within Ratt were definitely weird

“When they decided to fire Warren for whatever reason. I’m sure it was about business, but that was not a great business move. Once Warren was fired, I didn’t see myself being in Ratt anymore.

”I already went through situations in Quiet Riot where they were dumping people left and right, and I didn’t want to deal with that again. I don’t want to be in a band where the lineup is a revolving door. I wanted to be the way we were, but it got to the point where that was no longer possible. So, I didn’t want to do it anymore, and I told them I was done.”

How did you end up with King Kobra?

“Carmine [Appice] called and asked me to record a song or two on the new record. I said, 'Sure. Why not?' I guess they liked what I did because they asked me, 'Can you just do the whole record?' Once again, I said, 'Yeah, why not?' It’s refreshing, and I like working with those guys. I’ve worked with Carmine before on past projects and with Paul [Shortino] many times over the years, too.”

What guitars are you using these days?

“I’ve been using Gibson a lot. I still use Jackson and Charvel but mainly Gibson Flying Vs. I love them, and I’ve been recording with them for a long time. I still have the V that I got in the very early ’80s, and that’s mainly what I used on the new King Kobra record. I love the sound of them and the way they play. I don’t overthink it beyond that. They fit what I’m doing, and I like how they feel. They’re great guitars.”

Do you keep your pickups stock, or do you upgrade?

“With the Gibson guitars, I leave the stock pickups in there. I think they’re humbuckers in there these days. But with the Flying V that I got in the early ’80s, I put DiMarzio pickups in there. But their new ones sound so good that I don’t feel I need to change them. So the Gibson pickups are great, but as far as the Jackson and Charvel guitars, I still put DiMarzios in those guitars.”

And what combination of amps are you plugging into now?

“I am all about traditional tube amps. I’ve been using Soldano amps for the last 10 or 15 years, and they’re great. Aside from that, I like Marshalls because it’s hard to get rental Soldano amps when you’re on the road. I’d like to take them out or rent them, but they’re pretty rare custom amps, so I don’t always have that option. I usually go with Marshall JCM900s because they’re the most readily available; they sound good and are super-consistent in terms of what you’ll get.”

Does being lumped in with hair metal bother you?

“No, I don’t think it’s derogatory. Back then, everybody went crazy with their hairstyles. It really is true that it was a competition to see who could have the biggest hairstyle. [Laughs] We really were hair metal bands, so no, it doesn’t bother me. If anything, it’s a funny term that maybe makes you giggle.

”If anything, I’m proud of my hair metal heritage. I’m glad I still have my hair! [Laughs] It’s a memory of a certain time, and I guess that decade will never go away. People seem to love it, which is not bad for those of us who were there.”

If Quiet Riot were to call out of the blue, do you think you would ever consider rejoining?

“Oh, I don’t know. I try not to think too much about it. I guess if they want to continue, then that’s fine. One way to look at it is that the current lineup continuing only helps the brand and helps the name. But I don’t see myself doing that anymore… I can’t imagine doing it. I closed that chapter in my life and moved on.

”It was so long ago, and so much has happened. Going back seems out of the question for the most part. I jumped off that crazy train, and I don’t know if I can get back on it.”

Where do you go from here?

“Truthfully, sometimes I don’t even care about being in a band and touring anymore. At this point in my life, I’m sure I will probably be doing something with music, but exactly what that might be isn’t clear. I don’t mind recording records with people at this stage, but as far as heavy touring, I don’t know if I could do that anymore. I guess it depends on who it’s with.

“Beyond that, I’m sure I’ll make more music, play more Spanish and classical guitar, focus on making some interesting Latin music, and keep teaching guitar to my few students. It’s a lot of work to go out there and fly around these days. I’m still passionate about guitar, but interested in winding down rather than ratcheting up.”