Amid an unprecedented heatwave that has swept large swathes of Rajasthan since early March, Bishnoi farmers in the State’s Sriganganagar and Hanumangarh districts have made an innovative provision to quench the thirst of deer, blackbucks and other wild ungulates. The farmers have dug up troughs and constructed concrete ponds, many of them in their own fields, to provide respite to a population of 10,000 deer and blackbucks.

The soaring mercury levels owing to the early onset of the heatwave in the desert State have threatened wildlife, taken a toll on the quality of crops, caused the water level in dams to plummet and affected rural employment.

According to the India Meteorological Department (IMD), this March was the warmest in the country in 122 years since it began maintaining records. In mid-May, the temperature exceeded 45 degrees Celsius in all 33 districts of Rajasthan and the southwest monsoon is expected to be delayed owing to lesser intensity in its northward advancement, the IMD says. The monsoon is expected to enter the State after June 25. Till then, it is likely to reel under the heatwave.

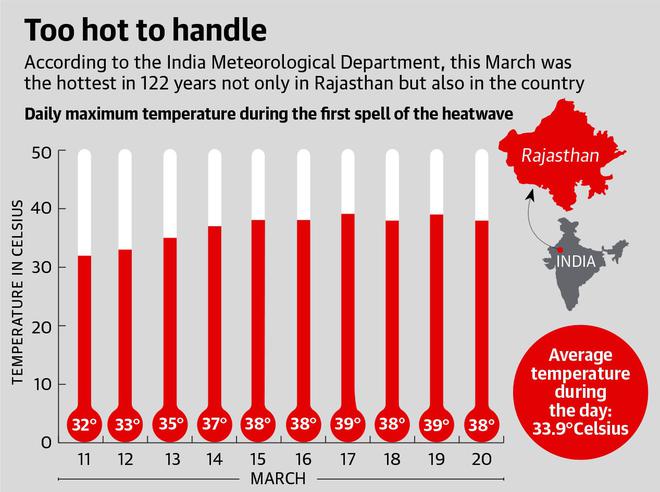

According to a preliminary observation of this year’s summer by the Central University of Rajasthan (CUoR), the heatwave’s first spell lasted from March 11 to 20. In 2021, the heatwave began on March 28, with the maximum temperature at 40.27 degrees Celsius. In 2020, it started on April 5, with the maximum temperature at 36.39 degrees Celsius.

This year, Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh experienced the heatwave for the highest number of days in the country, the study says. The absence of rain during this period aggravated the heatwave and even scanty rainfall could have brought the temperature down, it says.

“Our study of satellite data has revealed that conditions ideal for the heatwave will continue till the arrival of the monsoon. The impact of extreme temperature on environmental variables is serious this year,” says Laxmi Kant Sharma, associate professor at CUoR’s Department of Environmental Science. He says factors such as depletion of water for irrigation, evaporation of surface water and evapotranspiration from the green cover have exerted stress on sustainable water resources.

According to the IMD, an area is in the grip of a heatwave when there is a departure of 4.5 to 6.4 degrees Celsius from the normal temperature. When the maximum temperature is equal to or above 45 degrees Celsius, it is a heatwave, and if it is 47 degrees Celsius or above, it is a severe heatwave.

A heatwave, which can occur with or without high humidity, lasts more than two days and has the potential to cover a huge area, exposing a large number of people to hazardous heat, the IMD says.

Protecting wildlife

Farmers say their strategy of filling troughs and ponds with water in a 60 sq km area has helped save the lives of antelopes. Several antelopes drowned in the past while trying to drink water at the two major canals in the region — the Indira Gandhi Canal and the Bhakra Canal — which irrigate fields in arid areas. The concrete ponds for animals are situated in villages such as Hardayalpura and Lakhasar Rohi in Hanumangarh.

The initiative is led by Anil Bishnoi, a farmer and recipient of the State’s Amrita Devi Environmental Award in 2009. He says farmers in the region were requested to fill up troughs using water from tube wells. They are also replenished with water from the canals or the village water supply scheme, he says.

Apart from farmers and wildlife enthusiasts, Border Security Force personnel posted in western Rajasthan have contributed towards saving the lives of animals and birds amid the blistering heatwave. They regularly direct water tankers bound for border outposts to fill up tanks and ponds in and around villages facing water scarcity.

Forest officials say in dry deciduous forests in the State, the leaves shed during the summer have become nutrient feed for herbivores such as spotted deer and antelopes. The animals come to waterholes a few times during the day to quench their thirst, while most birds are observed drinking water several times and some taking bath in puddles to beat the heat. Despite the intense heatwave, waterholes in wildlife reserves and national parks in the State have reported some depth of water. Officials say mortality rates among both carnivores and herbivores are not alarming during the peak of the heatwave as they find spots to hide themselves under groves, bamboo clumps and canopies of dense trees. These green niches containing moisture are numerous inside forests.

A tigress named Riddhi was recently observed vomiting near Jogi Mahal inside the Ranthambore National Park. Forest officials treated her and offered her a bait to regain strength. Harsh Vardhan, secretary, Tourism & Wildlife Society of India, says while the heatwave has caused health problems in wild animals, flying squirrels and bats have the maximum mortality at peak summer. They are found in large numbers in south Rajasthan’s forests and the regions around Jhadol, Kotda, Dungarpur, Banswara, Kota and Baran, he says.

“They hang upside down from branches of large canopy trees like banyan and tamarind and fly to the nearest water source to quench their thirst, where they die because of weakness. Honeybees meet a similar fate during summer,” says Mr. Vardhan.

The forest authorities have made arrangements for water supply inside Ranthambore and Sariska national parks through tube wells powered by solar panels. The troughs situated nearby are filled up to invite the attention of all wild species. Each tube well supplies water to a minimum of three waterholes located at a distance of four to six km. While plastic pipes have been placed underground, iron pipes have been used where the surface is rocky.

Crop productivity hit

According to Prof. Sharma, the heatwave has also had an adverse effect on plant productivity in the State. The temperature extremes have affected pollination, one of the most sensitive stages in the life cycle of a plant. However, there was no effect on leaf area or vegetative biomass in comparison with normal temperatures, he says.

The temperature effects are intensified by a deficit in water and a reduction in the soil-water interaction or water holding capacity, says Prof. Sharma. Grain yield in the arid environment crop type has reduced by 80% to 90% from a normal temperature regime.

Farmers say the heat stress has affected the quality of wheat produced as a rabi crop, leaving an impact on its sale as well. The wheat grains harvested during the early onset of the heatwave have shrivelled. They have become thinner than their standard size and the impact is visible in 40% of the wheat produced. This has affected about 3.5 lakh farmers growing wheat in the State.

Dashrath Kumar, general secretary of the Hadoti Kisan Union, says the ban on wheat export had also led to reduction in wheat prices from ₹2,200-₹2,300 per quintal to ₹2,050 per quintal. “We have urged both the Central and State governments to procure all types of wheat for a bonus amount of ₹500 per quintal. So many families are dependent on this crop. The clause on standard size of grain should also be removed,” he says.

While the Food Corporation of India had procured a record 23.40 lakh metric tonnes of wheat in the State during the rabi marketing year 2021-22, the production is projected to decrease this year amid reports that a huge portion of the crop may become unfit for human consumption. Crops such as mustard, barley and chickpea have also been affected by the extremely high temperature in several districts.

Dams at risk of running dry

As a result of the heatwave, most dams in the State have low storage of water. They need good rainfall in their catchment areas this year to replenish their reservoirs to provide water for drinking and irrigation. Apart from the Kota barrage dam, which is almost 90% filled, all other dams have low levels of water, which will only last till mid-July unless there are heavy and widespread rains.

The Bisalpur dam in Tonk district — catering to the drinking water needs of Tonk, Jaipur and Ajmer — has 298.13 million cubic metres (Mcum) of water, which is 27% of its total capacity. As many as 449 of the 727 dams in the State are dry. Against the total capacity of 12,626.32 Mcum, dams across the State at present have water storage of 36.62% or 4,623.31 Mcum, according to the figures released by the State Water Resources Department.

The majority of the dams were filled up during the monsoon last year and the gates of several of them, mainly in the Hadoti region, had to be opened to release water. This year, the situation is serious mainly in Jodhpur division, where 123 dams have reached only 1.60% of their total storage capacity. Evaporation during the early heatwave and usage of water for irrigation have led to depletion of the water level.

Hansraj Godara, sarpanch of Lilala village in Barmer district’s Baytu tehsil, says the heatwave, accompanied by the closure of the Indira Gandhi Canal for two months for relining work, has created enormous difficulty for people in the region. “The canal is our lifeline as it quenches the thirst of western Rajasthan. Water supply from the canal restarted only recently after the relining work was finished,” he says.

In Jodhpur, the canal blockade was extended because of damage to the Sirhind feeder in Punjab. The local Hathi Canal that carries water to Kaylana lake and Takhtsagar lake, the natural reservoirs on the outskirts of the city, has also dried up. Residents of the city have been supplied with the limited water present in these reservoirs.

Jodhpur District Collector Himanshu Gupta has constituted an emergency response team for water supply management in the city and deployed the police force round the clock at filter plants in Kaylana, Chaupasni, Takhtsagar and Jhalamand to prevent theft and misuse of water. Water is being supplied in the city only once in three days. The administration has also decided to impose a fine on those wasting water.

Water scarcity has hit some parts of the State so badly that a special train carrying 40 lakh litres of water has been started for Pali district. The train has been making an average of three trips from Bhagat Ki Kothi suburban railway station in Jodhpur to Pali every day since mid-April. It has so far supplied 20 crore litres of water to the city. The North Western Railway has announced that the service will continue till the water crisis in the region is over.

The State government’s Public Health Engineering Department (PHED) has paid ₹3.24 lakh to the Railways for each trip. The water is emptied from the wagons into the tanks at Pali railway station and sent to the pumping stations of the PHED for supply to the city. The first water train for Pali, covering a distance of 70 km from Jodhpur, was started in 2005 when the main water source, Jawai dam, had dried up. The train was run thrice in the subsequent years.

On June 5, Pali Municipal Council chairperson Rekha Bhati and her husband completed a 300-km march on foot from Pali to Jaipur with the demand for laying a water pipeline between Rohat town and Pali. Ms. Bhati says a 28-km pipeline from Rohat would connect Pali to Jodhpur’s Kuri pumping station. “It would permanently resolve water scarcity in the city and obviate the need to run the special train,” she says.

Early migration of cattle herders

Hindu Singh Tamlor, sarpanch of Barmer’s Tamlor village, says the early arrival of the heatwave has affected the livelihood and livestock of people in western Rajasthan’s desert districts. “There is no grass available for grazing of animals in the traditional landscapes of Oran and Gochar, with the temperature hovering around 48 degrees Celsius.”

Mr. Tamlor says the heatwave has also resulted in the early migration of cattle herders from the desert area to the fertile Hadoti region in south-eastern Rajasthan and neighbouring Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat. Animal rearers, who raise sheep, goats, cows and camels, migrate to areas with green cover every year during the monsoon, but the early onset of the heatwave has forced them to leave to protect their livestock.

Throwing light on the impact of the heatwave on working class people and farmers, Prof. Sharma says the combined effect of the metabolic heat produced internally from heavy physical activity and the external heat from the surrounding environment contributes to high risk of heat stress. “Workers engaged in strenuous work outdoors are exposed to solar radiation, while those in indoor settings face the heat generated from work processes or equipment.”

Prof. Sharma says recent research has warned that climate change will intensify the duration and magnitude of occupational heat stress. The impact of rising heat in the workplace is likely to affect the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations. Heat-related illnesses will have a greater occurrence among agricultural workers, according to studies.

Experts say the relentless heatwave has also affected engine efficiency and fuel consumption of vehicles. CNG-powered vehicles and electric vehicles face issues with high temperature as battery efficiency and life reduce due to overheating, they say.

More heatwaves in the offing

Amid widespread and intensifying climate change, the trend of heatwaves starting early in the year is here to stay. In a recent landmark report, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has projected more intense heatwaves of longer duration and occurring at a higher frequency in the Indian subcontinent. Rajasthan needs to be prepared to face such fierce heatwaves and take adequate steps to protect its human inhabitants as well as its flora and fauna.