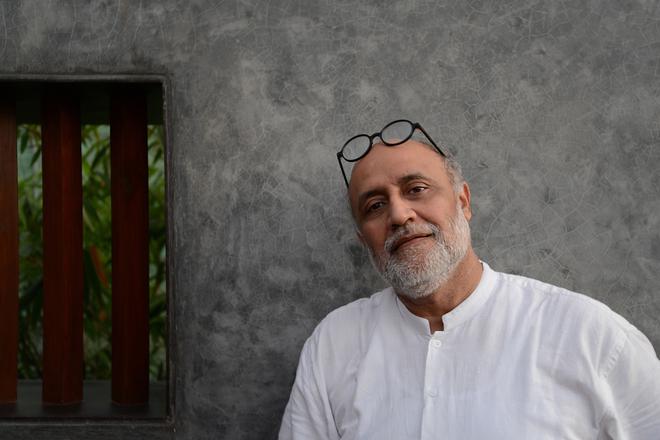

Architect Rahul Mehrotra is no stranger to the Venice Architecture Biennale. Principal founder of Mumbai-based RMA Architects, he is renowned for projects of varied concerns and scales such as the Hathigaon housing for mahouts and elephants near the Amber Palace, Jaipur, and the various interventions to the CSMVS campus in Mumbai. In the course of each of his Biennale appearances (in 2008, 2016, 2018, and 2020-21), he critiqued and theorised urban change, questioned the notion of permanence in architecture, and broke down the rigid hierarchies in spacemaking — bringing new ways of looking at India’s trajectories of urbanisation.

The 18th edition of the Biennale Architettura, curated by Ghanaian-Scottish architect and academic Lesley Lokko, is themed ‘The Laboratory of the Future’. Her vision is to foreground previously under-represented places and peoples by exploring alternatives in decolonisation, decarbonisation, and presenting ways of doing architecture that are different from the usual consumption of natural resources. In response, Mehrotra, along with cultural theorist Ranjit Hoskote and designer Isabel Oyuela-Bonzani, is presenting Loops of Practice, Thresholds of Habitability.

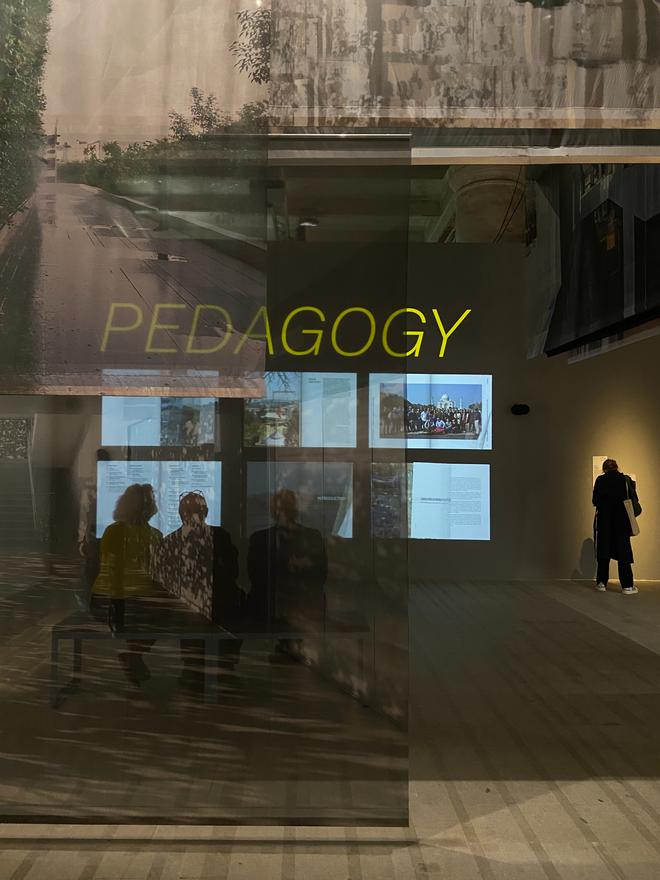

The exhibition uses the feedback-loop as a leitmotif to re-examine various aspects of architecture, design, research, writing, advocacy, and pedagogy that form the basis of Mehrotra’s practice. Sited in the historic Arsenale in Venice, it emerges out of a configuration of screens, large video presentations, displays and vitrines filled with documents, providing a chiaroscuro experience quite in keeping with its Italian setting. Edited excerpts:

Lesley Lokko’s central provocation is that the practitioner is an ‘an agent of change’. How did the three of you curate a response to this?

Hoskote: I believe quite strongly that the architect is well placed to be an agent of change in an unpredictable world shaped around shoals and currents rather than stable centres. They must address shifting patterns of policy, ecology, migration and livelihood. The [Marathi] saint-poet Tukaram speaks of building his house in the sky. In this spirit, contemporary architects must practice as a dynamic response to constant instability, rather than turning away into safe zones of patronage. Mehrotra’s three-decade-old practice achieved this, in a period beginning with the fall of the Berlin Wall and India’s move towards liberalisation, through globalisation and emergent totalitarianism. My approach was to develop a many-sided portrait of this productively hybrid practice, to regard it through multiple lenses, and see the connections.

Earlier exhibitions based on your practice and theories have been held here in Venice, as well as in Mumbai and Ahmedabad. How did this edition become a ‘laboratory’ to test your concerns in architecture and urbanism, especially in the Global South?

Mehrotra: Looking retrospectively at my participation at the Biennales since 2006, I found an intersection between the themes earlier curators had unearthed and my own research trajectories. This edition became an appropriate venue to synthesise previous learnings and to think about future practice formats. Ranjit’s formulation of the last 30 years of my various engagements, into a taxonomy of Research, Advocacy, Practice and Pedagogy, show their simultaneous validity for architects to work in the future. This proposition of a multiplicity of working modes is valid for more than what you refer to as the Global South, and could resonate for our interconnected planetary condition.

“Mehrotra’s practice carries forward the tradition of responding to the city as a macro-organism animated by irregular cycles rather than a system of neatly interlocking mechanisms.”Ranjit Hoskote

How do you unravel the complexities of a ‘multi-modal and multi-scalar’ work of an architect whose practice encompasses not only design but also advocacy, research, and pedagogy?

Hoskote: I have drawn on three decades of friendship and conversations, and articulated a survey of Mehrotra’s work as friend, fellow traveller, and collaborator. As I see it, his practice is a model for how architects, especially in the Global South, can intervene creatively and generatively in a public situation mired in bureaucracy, ignorance, and pessimism. His trajectory has evolved in a rhizomatic manner, in response to existing problems yet also in anticipation of crises to come — from policy deficits in urban planning, through discursive gaps between expert culture and emerging audiences and userships, to the need for establishing solidarities between theorists and activists in shaping resistance to misgovernance and legislated urban chaos.

We translated the ‘intangibles’ through scrims and screens that shimmer in subdued light; through an ensemble of the publications that embody Mehrotra’s varied collaborations and bear witness to the convenings and congregations through which his practice in research, advocacy, activism and pedagogy has elaborated itself. We have recycled elements from his previous appearances [that were stored at a colleague’s home in Padua] to reduce our carbon footprint. Through video documentary, we demonstrate the spectrum of dialogues and negotiations through which this practice takes shape, in a spirit of capacious responsiveness.

You have dismantled an idea sacrosanct to architects and planners — that of the permanence of the built form. You re-envision materiality as ecology rather than construction, where ephemerality is significant to understanding new urban milieus. Could you expand on these themes?

Mehrotra: The provocation I recite to myself when starting a project, or to my students is: are we making permanent solutions for temporary problems? Embedded in this is a call to examine material life cycles, ecological footprints, and even the relevance of building. The architecture profession today is sharply polarised — where we speak of a moratorium on construction and where we believe that building as a state of permanence continues to be relevant. I believe there is an in-between space of reversibility and of touching the ground lightly. My attempt is to infect the debate with this middle ground.

Are there alternatives to your critique of globalisation and the tyranny of images because of what you term ‘The Architecture of Impatient Capital’?

Mehrotra: I think what the Biennale proposes and what our exhibition does is consistent with this message. The Biennale tells us that the stories, the rearticulation of positions and histories, the inclusion of multiple voices, all inform how we reformulate our imagination of the built environment and its relationship with nature. In our installation, we question the notion of architecture being the central spectacle or even the privileged instrument to organise the city. Instead, through research, writing and design of pedagogy we can create a new generation of architects who will use these multiple modes that will hopefully inform how we spatially dwell on this planet.

“The provocation I recite to myself when starting a project, or to my students is: are we making permanent solutions for temporary problems? Embedded in this is a call to examine material life cycles, ecological footprints, and even the relevance of building. ” Rahul Mehrotra

How do you see Mehrotra’s practice (living and working in Mumbai) as an extension of the genealogy of urban visionaries like Patrick Geddes and Claude Batley, both of whose work impacted the city?

Hoskote: Through his co-authored books with Sharada Dwivedi, his work at the Urban Design Research Institute [UDRI] and the Architecture Foundation, his curatorial engagements with State of Architecture and State of Housing, and the nomadic studios that have resulted in the series of Extreme Urbanism readers, Mehrotra strongly embodies the values of this tradition.

In my foreword to Mehrotra’s collection of essays, The Kinetic City [ArchiTangle, 2021], I have placed him in a genealogy of visionaries who made Bombay/ Mumbai their home for varying durations, including Patrick Geddes, Claude Batley, Charles Correa and Kamu Iyer. Mehrotra’s practice carries forward their tradition of responding to the city as a macro-organism animated by irregular cycles rather than a system of neatly interlocking mechanisms. They were dissenters and critics, pragmatic idealists who identified crises in the making, proposed solutions to problems, and built platforms and institutions for debate.

The Biennale Architettura 2023 ends on November 26.

The writer is Professor of Architecture at Sir JJ College of Architecture, Mumbai.