A collaboration between palabra and the Texas Observer.

Early in the morning of September 15, two buses full of migrants arrived near Vice President Kamala Harris’s residence in Washington DC, sent by Texas Governor Greg Abbott. The day before, about 50 migrants came to Martha’s Vineyard on flights originating from Texas, but chartered by Florida Governor Ron DeSantis. These were the latest in a series of headline-grabbing provocations by three Republican governors, led by Abbott, who have sent thousands of migrants to liberal strongholds around the country.

In 1962, a nearly identical political stunt was pulled by a racist organization in Louisiana, sending hundreds of Black Southerners to Northern cities in a brazen attempt to get liberals to tie themselves in knots. Back then, the trips were called the “Reverse Freedom Rides.” Abbott’s buses started rolling earlier this year, but it wasn’t until DeSantis’s copycat flights landed migrants on Martha’s Vineyard that the media took note of how nearby Hyannis, Massachusetts had also been a target of the Reverse Freedom Rides.

Today, Abbott and DeSantis describe their efforts as attempts to highlight a border security crisis. Democratic politicians decry the taxpayer-funded transfers as racist and inhumane, and a “game of gotcha” that plays best on television news—Fox News and the streamed Fox Nation, in particular.

Since April, Abbott has sent more than 10,000 migrants—many of them Venezuelans exercising a legal right to seek asylum—from Texas to Washington, D.C., New York City, and Chicago, at a cost of more than $12 million, as part of his made-for-TV, publicly-funded initiative, “Operation Lone Star.” He has wasted few opportunities to pick fights with liberal politicians in destination cities or make arch pronouncements about migrant-friendly “sanctuary cities.” After the first Texas bus arrived in Chicago, Abbott announced in a press release, “Mayor Lightfoot loves to tout the responsibility of her city to welcome all regardless of status, and I look forward to seeing this responsibility in action.”

Migrants on these flights and buses have been met by representatives of city agencies and nonprofit organizations and given food and housing. But if Abbott’s goal was to create a sense of chaos in the North, he seems to have succeeded. In Washington Mayor Muriel Bowser requested National Guard assistance in July (her request was denied). In Chicago, Governor J.B. Pritzker issued a disaster proclamation because of the busing. And in New York, Mayor Eric Adams has blamed the preexisting crisis in the city’s strained shelter system on migrants bused from Texas.

Ahead of what is due to be a contentious mid-term election this fall, Abbot’s scheme has spread: Arizona Governor Doug Ducey has since sent at least 1,600 migrants, mostly asylum seekers, from Arizona. The Martha’s Vineyard flight appears to have been DeSantis’s first foray, although he promises more.

Many articles have noted the eerie resemblance of the migrant busing ploy and the Reverse Freedom Rides. But the similarities go beyond the headlines, and the Rides offer more than a sad reminder of how white supremacy repeats itself.

A closer look at the Reverse Freedom Rides reveals the underreported history of people who organized to combat or undermine the racist cynicism of the Rides—and offers some hope for 2022.

‘A strictly promotional venture’

When Louis and Dorothy Boyd stepped off a Trailways bus with their eight children at New York’s Port Authority Bus Terminal early on the morning of April 21, 1962, they were mobbed by reporters, aid workers, activists, and gawkers. Louis Boyd, an unemployed longshoreman from New Orleans whose public benefits had been cut off back home, was dazed and sleep deprived after a 41-hour bus ride with his wife and eight children. Still, he summoned the energy to give a statement to reporters.

“We’re tired of suffering,” he said. “I am not sorry to leave the South. There is nothing there for me.”

Then Boyd and his family were escorted to a hotel in Midtown Manhattan that had agreed to temporarily house them. The next day was Easter Sunday, and the Boyds, in swanky new outfits donated by a benefactor from the NAACP, showed up to worship at Concord Baptist Church of Christ, a venerable Black church on Marcy Avenue in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn. By Tuesday, Louis Boyd had found a job in Jersey City paying $100 a week (about $1,000 today; a 1962 dollar is worth, conveniently, just under $10 in 2022) and had promises from the Urban League’s Newark office to find him housing within walking distance of work.

“I selected them by the number of children they had and things like that.”

No one was happier to hear of Boyd’s success than George Singelmann, then chairman of the Citizens’ Council of Greater New Orleans, a racist nonprofit organization dedicated to fighting integration and equality. Singelmann had paid for the Boyds’ tickets to New York and given them $50 spending money as part of a publicity stunt called the “Freedom Rides North” or the “Reverse Freedom Rides,” a parody of the famous 1961 Freedom Rides, which had been a turning point in the Civil Rights Movement.

The Reverse Freedom Rides were no mere charity. They were a deliberate provocation by Southern racists to expose perceived hypocrisy in the North and West. Singelmann wanted to watch Northerners squirm at the thought of hundreds or thousands of Black people—he especially wanted poor single men and very large families—descending on their cities. In opposition to them, activists in both North and South organized to fight the rides themselves, and to support the people who were bused.

“It was strictly a promotional venture,” Singelmann recalled years later in a 1977 interview with historian Glen Jeansonne. He noted that “the more bizarre the situation,” the better story it made. “I selected them by the number of children they had and things like that,” he said, and “selected the destination on the basis of where I thought it would do the greatest amount of good to expose the hypocrisy of the community.” He sent Black Louisianans to places where “people were very critical but highly sensitive when it affected them.”

Singelmann’s vision for the Reverse Freedom Rides was expansive. He wanted chartered buses. He wanted a “Freedom Train” to carry as many as 1,000 Black Louisianans to Chicago. He wanted buses from Little Rock and Shreveport and Birmingham.

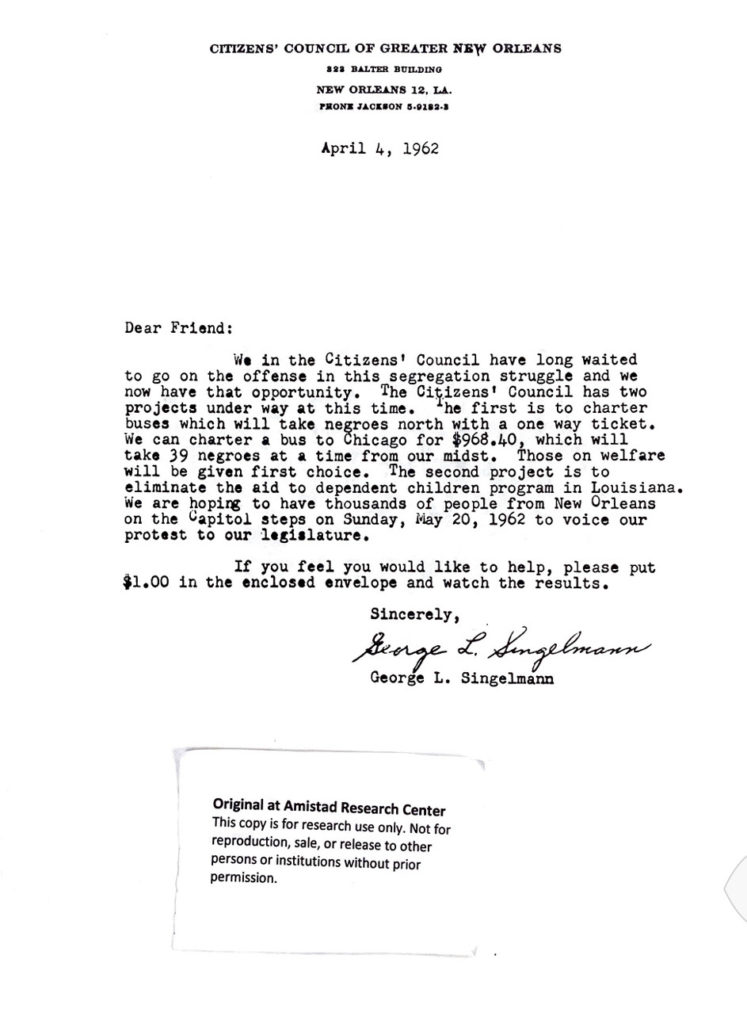

Singelmann rolled out his plan in a fundraising letter to members of his organization. “We in the Citizens’ Council have long waited to go on the offense in this segregation struggle and we now have that opportunity.” Each bus, he wrote, “will take 39 negroes at a time from our midst. Those on welfare will be given first choice.”

And when stories of Louis Boyd’s success appeared on front pages from New York to New Orleans, Singelmann knew he had done it. “That broke it wide open,” Singelmann remembered with audible glee in the 1977 interview. “There was just no end to it.”

Early May of 1962 saw the Reverse Freedom Rides explode. Riders arrived in New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, and even Hyannis, Massachusetts—a short ferry ride from Martha’s Vineyard—chosen because it was the summer residence of the hated Kennedys.

Northern politicians and organizations rushed to condemn the stunts. New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller said, “it violates every fundamental concept that we believe in.” Roy Wilkins, executive secretary of the NAACP, said it was “a naked pretense to maintain segregation. It’s cheap, unconscionable.” Similar sentiments were echoed by everyone from US Attorney General Robert Kennedy to local welfare directors in targeted cities.

Singelmann and others mocked these comments, much like Abbott, DeSantis and Ducey use social media today to ridicule critics of the migrant transfers.

Roy Wilkins, executive secretary of the NAACP, called the Reverse Freedom Rides “a naked pretense to maintain segregation. It’s cheap, unconscionable.”

Representative F. Edward Hébert of Louisiana feigned surprise at Wilkins’s statement. “Is it possible the NAACP has no genuine interest in the advancement of the colored people?” he archly asked a reporter for the Baton Rouge Morning Advocate.

“We are telling the North to put up or shut up,” Singelmann told a Newsweek reporter. The movement was only growing, he claimed. “We have more applications than we can handle,” he told a reporter. In another interview with the Baton Rouge Morning Advocate, he warned, “There is going to be a freedom bus a day, five days a week, to some darling city in the North.”

But those new buses did not materialize, and within six weeks the entire project was scrapped.

The remarkable disintegration of the Reverse Freedom Rides turned Singelmann from a formidable national figure into a laughingstock. In his far-right echo chamber, he had seriously misjudged the public response to his stunts.

Most importantly, Singelmann seemed incapable of understanding how savvy and creative Black nonprofit organizations were. By sending mocking letters to the NAACP and Urban League, he put experienced community organizers on notice about his plans. A report by the Urban League of Greater New Orleans recounts that, even before the first rider went North, those organizations had begun contacting churches, schools, community groups, labor unions, and others—including 500 Black educators in New Orleans for a conference—to warn them about the dangers of playing into Singelmann’s hands.

Activists fight the rides

Back on April 14, 1962, five days before Singelmann officially launched the Reverse Freedom Rides, the Louisiana Weekly, New Orleans’s Black newspaper, was already declaring the “Freedom Bus” a “silly fraud.”

Representatives of the Urban League met with station directors at mainstream radio and TV stations in New Orleans and New York, ultimately placing editorials excoriating the rides at five or more stations. One, broadcast multiple times on both radio and television at the New Orleans NBC affiliate, called the rides “sick sensationalism bordering on the moronic.”

These messages were more than simple reviews. The NBC station’s statement, aired on April 24, 1962, continued by saying, “No organized move is needed to stimulate outward migration of Negroes.” It went on to describe what would have been obvious to Black viewers but was invisible to Singelmann: Millions of Black people were already leaving the South, in what is known as The Great Migration. By that time, more than 400 Black Americans were fleeing the South every day. What was an extra busload here or there?

In the face of community backlash, Singelmann had a hard time finding takers, and he subsequently had to work overtime to cover up the small size of the rides. When reporters tried to verify claims he had sent 103 Black passengers on buses to Chicago, they found nothing. Within days of the first ride in April, reporters were already asking Singelmann about delays and setbacks. He spoke bitterly about “Negro indecision,” saying any intimation that things weren’t going to plan was “lies or misinformation.” By August, the whole plan had been scuttled.

Most of the people ultimately sent on the Reverse Freedom Rides had accepted the tickets in good faith, only to find that they had been cruelly used for publicity by racists back home. There was no shortage of human suffering.

Other riders did see through the ploy. A New York reporter recognized one as Leon Horne, a seasoned activist already living in Chicago, who had been arrested in Jackson, Mississippi on the original Freedom Ride.

“Man, I like these ‘free rides,’” Horne said with a wink, before adding, “I made a chump out of Mr. Singelmann!”

Jokes about the rides abounded in Black media. The Chicago Defender, the legendary Black newspaper, ran a cartoon in which a man muses about going back to the South to visit his sister “then get the White Citizens Council t’send me back!”

Singelmann aimed to expose the weakness and hypocrisy of his intended targets, but in fact the Reverse Freedom Rides allowed city governments, civil organizations, and Black media to showcase their strength and humanity in ways that are instructive for today.

Politics and buses

Sixty years after the Reverse Freedom Rides, Governor Abbott has expanded on Singelmann’s vision.

Where Singelmann was ultimately able to move only some 200-300 people in the Reverse Freedom Rides, just five or six of Abbott’s buses can hold that many. Singelmann spent $20 to $50 per ticket ($200 to $500 today). Abbott, dipping into public funds, has spent more freely than Singelmann ever could.

By August 9, 2022, Abbott had paid Wynne Transportation more than $12 million from state coffers for migrant transportation, according to documents obtained by CNN — that’s more than $1,400 per person. (The El Paso Times has noted that booking same-day flights would have been substantially cheaper.) According to the same documents, only $167,828 came from private donations. Texas has not released up-to-date numbers, but documents obtained from the state of Arizona by American Oversight indicate that costs for that state’s program run in excess of $82,000 per bus.

Abbott insists he only buses volunteers, but he has, literally, a captive audience of migrants who may have limited access to legal counsel from private firms or aid organizations.

There are, of course, significant differences between the people bused on the Reverse Freedom Rides and migrants bused today.

Language was not a major barrier for Black Southerners, as it is now for migrants crossing Texas. Back then, the Citizens’ Council needed to convince Black people to leave their homes to take a chance on a city in the North. Today, Abbott is targeting people who already are, by definition, far from home.

The most important difference is also the most obvious: However oppressed, however heavy the boot on their necks, Black Americans were U.S. citizens, moving within their own country. They were documented; their legal residency—if not their civil rights—was uncontested.

And yet, the similarities between Singelmann’s and Abbott’s campaigns are striking. Behind the stunts are powerful, deep-pocketed white men trying to get one over on political opponents and “own the libs.”

“What could we do with that money if we were to set out humane goals of welcoming people?”

“Republicans have been pushing the boundaries of the acceptable, the moral, the ethical, and the legal,” said Dylan Corbett, founder and director of Hope Border Institute in El Paso. “It’s pure theatrics. It doesn’t help anybody. It doesn’t help border communities, it doesn’t help migrants, and it doesn’t do anything to address what’s happening at the border.”

As in 1962, humanitarian organizations have stepped up. Sixty years ago, it was Travelers Aid and the Urban League in New York that did the heavy lifting; today, the Central American Resource Center (CARECEN) and SAMU First Response in Washington D.C., among others, have been doing heroic work and are now being backed by influential Democratic politicians.

Despite being used as pawns, some migrants being bused today will eke out a better life, just as some of the Reverse Freedom Riders did. Indeed, Abel Nuñez, executive director of CARECEN, said that the busing might have a silver lining. He pointed out that most migrants want to move on from Texas anyway, and Abbott, DeSantis, and Ducey are inadvertently helping some people accomplish that goal. “I don’t think on purpose,” he said, “they are getting them closer to their final destination, whether that is because they want to get closer to a family member or because they just want to get closer to New York.”

Kassandra Gonzalez, a staff attorney with Texas Civil Rights Project emphasized the exorbitant expense of the buses and flights. “This scheme demonstrates the huge amount of resources that can be mobilized when the state’s objective is to exact cruelty on vulnerable people seeking safety,” she said. “What could we do with that money if we were to set out humane goals of welcoming people?”

If the Reverse Freedom Rides hold out a simple lesson, it is this: In the spring of 1962, after welcoming the Boyds to his church in Bed-Stuy, the legendary Rev. Gardner Taylor, himself a former Louisianan, said, “This great city throws wide the gates of the heart to Mr. and Mrs. Louis Boyd. If the white supremacy groups want to keep sending Negro families, we’ll keep receiving them. We’ll break the White Citizens Councils’ treasury!”