Christina O’Rourke was perched on the bow of a 46-foot sailboat called Skye on a sunny July afternoon as the vessel glided past the breakwalls into Lake Michigan’s open water.

The excursion was another opportunity for O’Rourke and her fellow crew members to sail ahead of this weekend’s Race to Mackinac, an annual competition hosted by the Chicago Yacht Club.

The journey from Chicago’s shoreline to Michigan’s Mackinac Island, sandwiched between the upper and lower peninsulas in Lake Huron, is long, and the competition is stiff. Among the other entrants is O’Rourke’s younger sister Meghan, racing on the boat Hot Lips.

For the Glenview natives, this is no mere friendly sibling rivalry. The race offers them an opportunity 100 years in the making to bring a Mackinac trophy back to O’Rourke family hands.

A century ago, their great-grandfather John P. O’Rourke and his brother James sailed the 1923 Race to Mackinac in their small Q boat — a once-fashionable model rarely seen today. The brothers fought their way to an improbable victory on behalf of the Jackson Park Yacht Club.

But their glory was short-lived. Months later, the O’Rourkes were disqualified on a technicality.

The story of a great win — and subsequent dismissal — has become family lore.

“To me, the Race to Mackinac was always like this legend that I think we were aware of from a really young age,” said Christina O’Rourke, 35, a Glenview resident who works in advertising for United Airlines.

Despite their family connections to the sport, the O’Rourke sisters didn’t start sailing until their mid-20s. They quickly became consumed with being on the water.

“One thing I love about sailing and why it’s so important to me is because you have land problems and when you go sailing, you leave them on land,” said Meghan O’Rourke, 34.

“Your whole world kind of shrinks to the size of the boat,” her sister said.

After introductory courses, hours on boats and learning to feel steady on their sea legs, the sisters decided to take on the race they heard so much about as children. This year is their sixth time sailing the Mac.

The Race to Mackinac began in 1898 with just five boats, according to the Chicago Yacht Club. In the 125 years since, it has ballooned into what sailing enthusiasts describe as a bucket-list race, attracting entrants from around the world.

After starting Saturday just beyond Navy Pier, this year’s race, with about 2,000 participants on 245 boats, should see sailors step foot on the island in two or three days — after working around the clock in shifts to get there. That is, if all goes well.

At 333 miles, it’s the longest freshwater race in the world. The distance makes the Mac a test of endurance, will and preparation. Winning requires the right group of sailors with the right set of skills and the ability to weather whatever the lake and sky present, according to race chairman Sam Veilleux. Last year, intense storms propelled boats to the island swiftly.

“I don’t ever want to get up there that quick again,” Christina O’Rourke said.

Yet, when the elements get rough, there’s comfort for her in knowing her great-grandfather charted the same waters. When she’s racing the Mac, Christina O’Rourke said, she finds herself wondering about him.

“It does mean a lot to me to have that connection,” she said.

Keeping a family dream alive

The 1923 race attracted 17 yachts, including the Intruder — John O’Rourke’s boat. The comparatively small vessel was seen as a longshot to win, but its size proved beneficial in that year’s weather.

“Intruder, perfectly sailed, meeting good luck, made one of the gamest races of the big fleet,” the Chicago Daily Tribune reported.

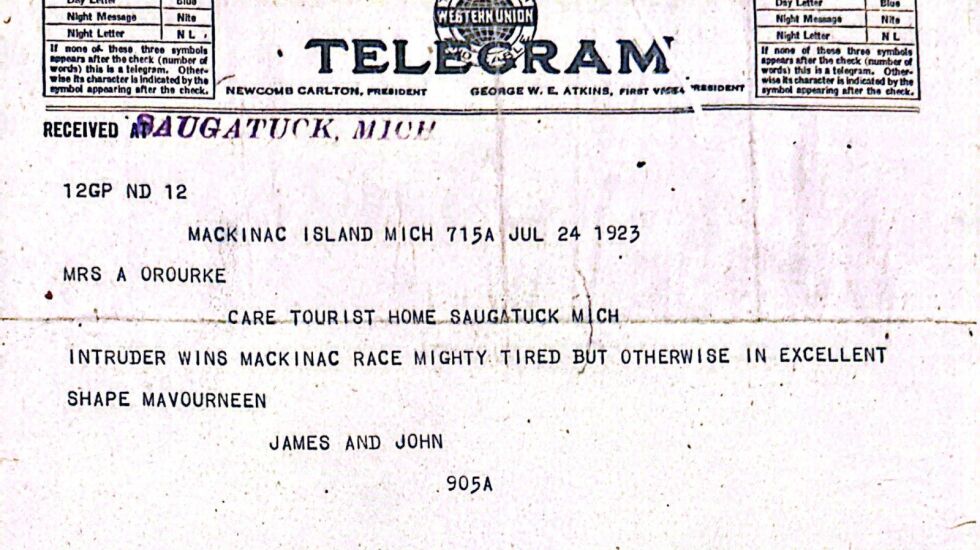

On reaching land, the O’Rourke brothers sent a telegram to their family to announce their win and said in it: “Mighty tired but otherwise in excellent shape.”

Once back home in Chicago, though, their luck took a turn.

What really led to the disqualification 100 years ago probably will never be definitively known. According to Chicago Yacht Club documentation from that time, John O’Rourke failed to submit a proper certificate of measurement. That paperwork helps determine each boat’s handicap.

After the race, the host club said O’Rourke didn’t comply with orders to remeasure his boat.

About three months later, the race committee voted to disqualify the Intruder and two other boats from the Jackson Park Yacht Club. It awarded the victory in the race to a Chicago Yacht Club boat, the Virginia.

It was reported that John O’Rourke accused the committee of unethical practices and favoritism. But his appeal to the Lake Michigan Yachting Association was denied on the grounds he incorrectly filed the appeal directly to the association rather than with the race committee.

O’Rourke’s descendants have heard a lot of speculation about what happened in 1923, from cheating to gambling on the race. Another well-known tale is that the race organizers didn’t like South Side Irishmen defeating the host club.

Robert J. Wiesen, manager of the Chicago Yacht Club’s Race to Mackinac history project, said all of that is just “scuttlebutt” and that it was merely a matter of enforcing the rules.

The disqualification heightened tensions between the two yacht clubs. But today, a century onward, there’s a sense of camaraderie.

“Nowadays, all the yacht clubs work together to support the sport of sailing,” Christina O’Rourke said. “Back then, they were huge rivals.”

In 1936, the commodore of the Chicago Yacht Club tried to woo John O’Rourke back to the Mac, writing to him that things had changed since 1923.

“Dimly I remember some kind of mix-up which you had with our race committee and while I forget the circumstances, I remember it as one of those things which are not happening much nowadays,” reads the letter, which the O’Rourke family still has.

Marlon Harvey, the current Jackson Park Yacht Club commodore, hadn’t heard the speculation that the O’Rourkes might have been scorned for being Irish but said, “it sounds like Chicago.”

Today, Harvey said the South Side Club is probably the most diverse in the city. Still, he said he’s cognizant of sailing’s segregated past and said there was a time when he, a Black man, wouldn’t have been welcomed at the club he now leads. Harvey said sailing still has a reputation of being inaccessible. There are barriers to entry, such as the cost. He said that’s why he champions youth sailing programs with scholarships for neighborhood kids.

The O’Rourke sisters, too, want to help widen access to sailing, to get more women involved in a sport still dominated by men. They know their spot in the race would likely shock their great-grandfather.

“I think he would be surprised his granddaughters are doing it and not his grandsons,” Meghan O’Rourke said. “And then he would also be, like: Heck, yeah.”

Ahead of the centennial anniversary of his storied journey, the sisters said they would be pulling for each other.

“I just want to say good luck to Christina,” Meghan O’Rourke said.

“I’ll wish Meghan the best race as well,” Christina O’Rourke said. “Fair winds and following seas to the Hot Lips crew.”

Each, of course, wants to be the sister to come out on top. But they said they share a lifelong goal: to bring a victory back to the family — no matter how long it takes.

Contributing: Lauren Frost, Justine Tobiasz