R.L. Stine has never talked to another Stine from Ohio before. Excluding my immediate family, neither have I.

"Your grandfather couldn't spell either," Stine says, joking about how our shared "fake name" means "a lifetime of grief . . . They came over from Russia and they just took a name, but they couldn't spell it."

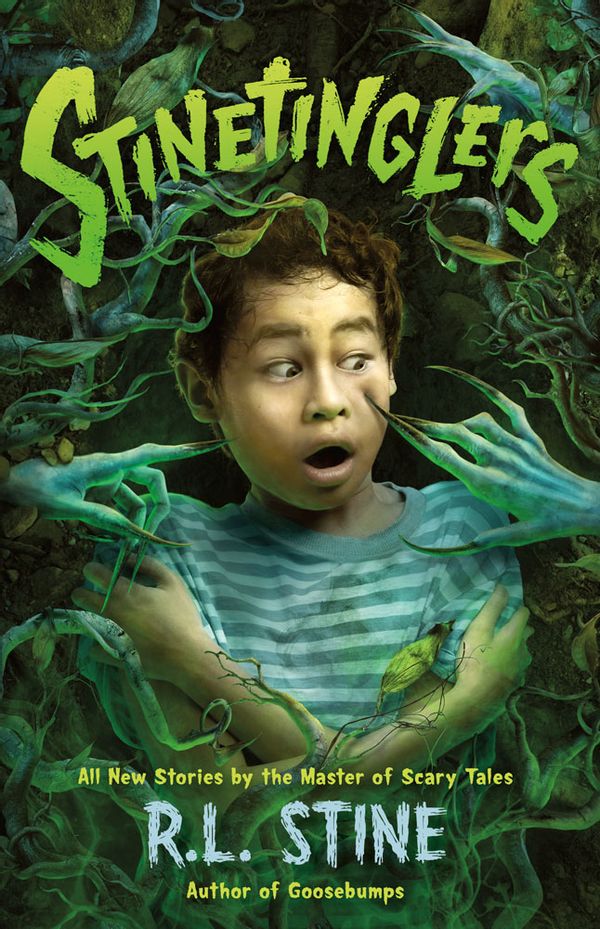

"We got out, right?" Stine, who grew up in Columbus, Ohio, says. The writer is speaking over Zoom from his home in the Hamptons, where his grandchildren have just arrived. And on Aug. 30, his new book did as well: "Stinetinglers," the first in a planned series of short stories for middle-graders. "It's like writing 10 novels. Why did I think I would enjoy that?" Stine says, growing serious when he admits he's very proud of the book.

He's written hundreds, some under pen names Jovial Bob Stine and Eric Affabee. His "Goosebumps" series has more than 350 million English language books in print and has been translated into 32 languages. "The Goosebumps" TV series was America's No. 1 children show for three years running, the Stine anthology series "R.L. Stine's The Haunting Hour" won multiple Emmys, and he has a new series for Disney+ called "Just Beyond," starring Mckenna Grace. Jack Black once played him in two feature films. Stine's other book series include "The Nightmare Room," "Garbage Pail Kids," "Mostly Ghostly" and "Fear Street." Adapted into a film trilogy by Netflix, all the "Fear Street" movies reached No. 1.

But his path to success wasn't easy — or a straight line. Stine started out hoping to write novels for adults and ending up working for a soft drink industry magazine. His first children's writing job resulted from answering a classified ad, and his horror writing break came after an editor was angry at someone else. Stine may be one of the best-selling children's authors in history, but his lessons about storytelling and perseverance apply to people of all ages.

Salon talked with Stine about his new book, the "Fear Street" movies, his theory of endings and how he feels about horror.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Did you always know that you wanted to be a writer? Did you write as a child?

Since I was nine. But when I was in fourth grade, I started doing these little comic books and drawing them. I had this superhero . . . He was a horrible superhero. I would bring comics into school and pass them around to get attention because I was a very shy kid. And then I looked around — and everyone else started drawing comics. There was a big comic fad in fourth grade, and everyone could draw better than me. Everyone said, "Your drawings suck." They were right. I had no talent at all, I couldn't draw.

"It was nothing but rejection slips. And I had to earn a living."

I knew I could write. I found this old typewriter and I would stay in my room for hours, hours, typing stories, typing joke books, typing. I was a weird kid. Why did I like it so much? I don't know. My parents didn't understand it at all. My mother would stand outside my door saying, "What's wrong with you? Go outside and play. Stop typing, go outside." Worst advice I ever got, right?

It's funny how a writer emerges from a family. Because my family was the same way. Nobody wrote.

Well, my parents were very uneducated, and very poor. My dad was a blue collar worker in a warehouse and he never actually read a single thing I ever wrote. They just didn't get it. But where did it come from? I can't explain it. Why? I think it had something to do — I hate being this serious, but it had something to do with being an outsider. Because we were desperately poor. And we lived right on the edge of a very wealthy community in Columbus. It was all rich mansions in the next block, and we were next to the railroad tracks in a little tiny house. The Governor's mansion of Ohio was a block away from us. I felt really that I didn't belong. I think maybe that's one reason why I stayed in my room writing all the time.

Did you have books that you loved growing up?

I read only comics. I was a comic book freak. My friends and I would carry around big stacks. We would trade them and read them under this tree in the front yard . . . When I was a kid, there were these EC horror comics that were incredible: "Tales from the Crypt," and "The Vault of Horror." They had this amazing artwork. And they were ghastly, horrible, bloody stories, all with the funny twist ending. There was always a funny ending. And I think they were very influential on me. I mean, that's kind of what I do to this day.

My mom dropped me off one day, I guess I was 10, at the Bexley Public Library on Main Street. The librarian was waiting for me and she said, "Bobby, I know you like comic books. I have something else I think you'll like." She took me to a shelf of Ray Bradbury stories and changed my life. Those stories were so great. I couldn't believe it. They were so imagined. They were so beautifully written, and all had great twist endings.

Everything that's happened to me is an accident. A horrible accident. No, I was desperate to get to New York after Ohio State to be a writer and I planned to write humorous novels for adults. I had all these ideas for funny novels for grownups, and of course, no one wanted them . . . it was nothing but rejection slips. And I had to earn a living. I didn't know anyone in New York City. It was pretty brave to move from Columbus when I didn't know anyone. So, I had to take a whole bunch of jobs. I was working for one year, a horrible year, at a magazine called "Soft Drink Industry," writing about bottle caps and syrups and flip top cans, and it was awful.

Then I got a job at Scholastic. I just answered an ad in the paper on Junior Scholastic Magazine, writing history and geography. That was the first time I ever wrote for kids . . . My wife was doing a magazine for kids called Dynamite and it was the biggest kids' magazine in the country . . . It was doing so well, they let me have my own magazine, which was a humor magazine called Bananas. That was my life's dream. I had my own humor magazine for 10 years. I never planned to do anything else.

"It was at that point in my career where you don't say no to anything. I'm still there, I still say yes to everything."

One day I was having lunch with Jean Feiwel who was a publisher at Scholastic and a friend. She arrived at lunch angry. She'd had a fight with a guy who wrote teen horror, who shall remain nameless. She said, "I'm never working with him again. Go home, you can write a teen horror novel. Go home and write a book called 'Blind Date.'" She even gave me the story.

Oh wow.

I didn't know what she was talking about. What's teen horror?

But it was at that point in my career where you don't say no to anything. I'm still there, I still say yes to everything. I ran to the bookstore to see what teen horror was. And I bought Christopher Pike books and Diane Hoh, and a whole bunch of people. I read them and tried to figure out what I could do different in mine. I wrote this book "Blind Date." It was a No. 1 bestseller. [I thought] wait a minute, what's going on? I thought kids liked me. I said, "Forget the funny stuff. I'm going to be scary now." And I've been scary ever since . . . But you can see it was all an accident.

A happy accident.

I mean, it worked out.

Some of your earlier books, like the "Goosebumps" books, for example, they didn't get a lot of publicity initially. Why do you think your books became bestsellers? Why do you think they became so popular?

Secret kids network. That's how all the book crazes catch on. You can't advertise books for kids and get them to buy them. There was no hype for me and no one really knew me. And the books did sit on the shelf for a while. But we had three "Goosebumps" books out, and then somehow kids discovered them and brought them into school and showed them to their friends. It's kids telling kids. See, the secret kids network. And soon it was all over the world. It was selling everywhere, just because of kids. I'm sure that's the way "The Hunger Games" went. That's the way "Harry Potter" went. It didn't come from advertising or hype. The "Twilight" books, all those book crazes, they were just — it was done by kids, I think.

Kids seeing other kids reading them and telling their friends.

And they're in school so they can show them to each other.

Do you think that when you became a parent — I know you're a grandparent now, too — did that change your writing?

I had other people to spy on. It's really important. When we started "Goosebumps," my son was the right agel and I could spy on him and his friends and see what they wore and what they talked about. And you know, you have to kind of stay in touch. I try to stay in touch with kids' culture and music and everything. Because you don't want to sound like some old guy, right? That's a really important part of the job.

I know that you have written your novels for adults as well.

Well, no one noticed.

Do you still prefer writing for kids?

I don't know why anyone would want to write for adults. Seriously. Because my audience is the best audience: 7- to 12-year-olds. I get them the last time in their lives they'll ever be enthusiastic.

I'm the parent of an 11-year-old. So, I agree with you.

You have one more good year. Because when they're 12, they discover sex, and they have to be cool. And then you've lost them. They don't want to know if I'm an author. Middle grade kids, they want to write to you, they want to talk to you, they want to buy stuff from you, they want to see pictures. And then by 12, they're gone.

It's such a neat age as a parent because my son shifts from being a little kid to trying to be a teenager, sometimes in the same sentence.

I'll never forget my son sitting on the couch in the living room, holding his teddy bear and singing, "Welcome To The Jungle." You know, Guns N' Roses. He was sitting and holding his teddy bear while he was singing it.

How do you know what's the right level of scary to write for this age? What's the right amount of creepy?

The important thing is to have a happy ending. They have to know it's going to end well. And then they don't get too scared. I try to make them know that it couldn't happen in real life . . . They have to know it's a fantasy and it couldn't really happen. If they know that, you can get pretty scary. But you have to let them know. And there has to be a happy ending.

I was going to ask you about your theory of endings.

"Even my life isn't R-rated. I've never had an R-rated thing in my life, and here are these teenagers being slashed to bits."

I did this one "Fear Street" novel, and just for fun, for me, I gave it an unhappy ending. The good girl is taken away as a murderer, and the murderer gets off scot-free. I thought it was funny. Kids hated this book and they turned on me. I started getting mail immediately. "R.L. Stine, you moron! How could you write that? You idiot! Are you going to write a sequel to finish the story?" And it haunted me. Or, I'd go to schools and speak at assemblies. Every time, some kid raised his hand. "Why did you write that book? How could you write that?" I had to write a sequel. They couldn't stand it.

I assume the sequel had a happy ending?

Yes. The murderer was caught.

I watched my own movies, for sure. I was shocked by them. They're R-rated. I've never had an R — even my life isn't R-rated. I've never had an R-rated thing in my life, and here are these teenagers being slashed to bits. They were slasher movies, and I was kind of shocked by it. But people love to see teenagers get killed. They love that. They love it.

All three movies were No. 1 on Netflix. And in a way it was kind of liberating for me to see I could get away with that. Because it never would occur to me to do that kind of a movie. Also, it helped that they were really well done. They were well directed and well written, and the young actors were all fabulous, and that helped a lot. But it sort of loosened me up a bit.

I'm doing this line of comic books for Boom Studios for adults, not for kids. They are horror comics called "Stuff of Nightmares." It comes out next month, the first one. And it's kind of loosened me up. It's for adults, so I have a lot of blood. It's a lot of gore and something probably I wouldn't have done before.

Do you have a different writing process for different forms, writing the comic books for adults as opposed to stories for children?

I do an outline of everything I write first. I never sit down. Ken Kesey said, "You sit down and you write a book"— never done that. And people would always say, "Well, what do you do about writer's block?" I say, I do a chapter by chapter outline of everything first. And when I sit down to write the book, I know everything that's going to happen. I've done all the thinking. I've done all the hard part. I know the ending. I know the middle. And if you do that, you can't have writer's block. Then you can just enjoy the writing.

I'm not really into horror.

I'm Stephen King for kids. And I'm always looking for some clever horror film. Every once in a while, one comes along that's really good. I love all the classic horror films, all the old Universal: "Frankenstein," "Dracula." I love those films. Megan Fox has a horror film called "Till Death." Watch that; it's pretty good. But I read mostly mysteries and thrillers and current fiction. I don't read a lot of horror.

I like horror movies a lot, but I'm often disappointed. I guess I don't know what's wrong with me, but I'm always looking for something else.

You want those twists.

I want to be surprised.

That's all I care about, the surprises.

You mentioned your comic books for adults. Do you have anything else coming out?

This is the 30th anniversary of "Goosebumps" this year. That's why I look like this: 30 years of this stuff. We have a special hardcover "Goosebumps" book coming out called "Slappy Beware." It's the first hardcover, illustrated "Goosebumps" book for an anniversary special. Then, because I'm nuts, I started a new series of short story books for Macmillan called "Stinetinglers." It's a book of 10 short stories, which — I've done short stories, what a crazy idea. It's like writing 10 novels . . . But it came out really good. I'm actually very proud.

My editor was joking that you took the title for my memoir. Now I can't write a book called "Stinetinglers."

Well, you probably could.