Lauren John Joseph (who uses they/them pronouns) has been producing art works in multiple genres for almost two decades. Their debut novel, At Certain Points We Touch, is receiving well-deserved attention and accolades.

At a time when transgender identities are debated as an issue with “two sides” in newspapers, as though some people’s very existence is questionable, it is refreshing to read a trans story where gender is not the main plot point. The novel explores themes of love, betrayal and grief through a queer love story, which may be better described as a tragedy.

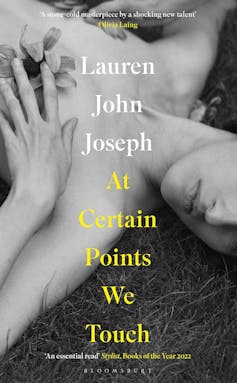

Review: At Certain Points We Touch – Lauren John Joseph (Bloomsbury).

The narrator, JJ, is mourning her lover Thomas James, who called her “Bibby”. She is addressing him in the wake of his death. The novel reads, as a result, as a second-person narration, drawing readers into their doomed relationship, as though we are all Thomas.

JJ’s account is loving, lustful, furious and regret-filled. Her descriptions of Thomas are blunt, unflattering and shocking.

Much of Thomas is uncovered in JJ’s retelling of erotic scenes between the two. Their intimacy was passionate and explosive, but also made JJ wary of how Thomas perceived her and other queer, trans and gender-diverse people. She reflects:

You had sex in a certain way, but you weren’t defined by it, certainly you had no loyalty towards other queer people, and absolutely no interest in the fight for visibility or equality. You were mean about anyone campy or swishy, unless they were nailing you, of course.

JJ speaks cuttingly of Thomas’ politics, just as he always spoke cuttingly of her political and activist leanings:

You were the kind of gay man who would have said that refugees who drowned crossing the Mediterranean had only themselves to blame, who would have agreed that all those UKIP dickheads were simply saying what needed to be said, and sometimes I’m almost glad you died before you had the opportunity to vote for Brexit, or start bemoaning the destruction of the English language as brought on by people who used neutral pronouns.

These revelations are hurled at the reader via Thomas. If he was at all likeable before this, our sympathies most likely end here.

Read more: Pages and prejudice: how queer texts could fight homophobia in Australian schools

Queer literary fiction

As a gender-diverse writer and researcher, I spend a lot of time thinking about how gender and sexuality are represented in literature. It is interesting to note that JJ’s gender is, in some ways, in the background of the story. Her gender identity is not something she questions or wonders about at length.

This makes At Certain Points We Touch different to many novels about transgender and gender-diverse identities – by trans and cisgender authors – that have had mainstream success.

Some of JJ’s descriptions of her romantic and sexual encounters are, however, revealing about the way she wants to experience her gender in the world. On her relationship with Thomas, she muses:

your ambivalence, when it came to the specifics of the body you were attending to, made my own gender, for the first time, feel weightless and irrelevant, and I’m so grateful to you for that, my blue-eyed bastard.

While Thomas was, perhaps, ambivalent to “specifics of the body” in his sexual partners, we learn about the conflicting ways that JJ and Thomas viewed sexuality and queerness:

I can’t ever imagine you calling yourself queer (though your sexuality definitely was), and there’s no way you would ever have allowed yourself to be spoken of as pansexual, or marched under any nom de guerre that carried hints of discourse or wafts of patchouli.

Part of what makes the novel so compelling is wondering how this complex relationship lasted as long as it did, with Thomas’s internalised homophobia and self-loathing often directed at JJ.

Read more: Friday essay: transgenderism in film and literature

Queer and millennial, or just a novel?

Some of the press around Joseph’s debut has focussed on it being queer and millennial. For a supposedly “millennial” novel, it is surprisingly detached from the internet, apart from emails being central to JJ and Thomas’s correspondence, along with many letters.

I’m a millennial, so maybe a “millennial novel” just reads like a novel to me.

I appreciated At Certain Points We Touch for its playful, experimental style and tone, and the way it incorporates autofiction into the plot. In the prologue, JJ asks Thomas: “When did you know you were dead?” In the first chapter, JJ takes out her computer and writes this line.

Later, in one of the novel’s most dramatic scenes, JJ tells the disdainful Thomas that she is writing autofiction, explaining that

in this act of writing I am making something new: one part biography, one part fiction, two parts slash, and in this new world, the world on the page, the world the writer has so steadfastly overseen, you are still alive.

Joseph also weaves in a range of cultural references to the likes of David Hockney, Bette Davis, Barbara Streisand, Maggie Nelson and Friends. The novel is a wild romp through London, through British culture, society and history; it takes us to San Francisco, New York and Mexico City. We experience these places in relation to JJ’s queerness and her urgent need to write.

One of my favourite sections is when JJ refers to the process of becoming a writer as “an awkward, gradual process, not unlike coming out of the closet”. She elaborates:

In the same way that I have passed from bisexual, to gay, to queer, to trans, I had to move through various disingenuous mutations as an artist, before I could become that which I really am. It would have been as impossible for me to declare myself a serious writer back then as it would have been to definitively stake a claim on femininity; neither seemed attainable modes of beings, except through disdainful irony.

JJ’s reasoning, which perhaps draws on Joseph’s own experiences, provides great insights into writing and queer, transgender and gender-diverse identities. It captures self-doubt and dysphoria in a way that is relatable and oddly comforting. Her comparison between writing and coming out is particularly significant in a novel that depicts writing as a method for unpacking one’s identity and relationships – gradually, in stages, with some realisations arriving too late.

Class and poverty

Class is central to the novel and to JJ’s aspirations. She says:

Very early on I came to know that indigence was the one unforgivable sin; that I would have to divorce myself from it through education, through my work, or succumb to its vices totally.

Being transgender makes her dreams more challenging. She remembers doubting that it would ever “be permissible for a person to be working class, transgender and successful all at once”.

Through this dynamic, Joseph explores the experience of being fetishized on account of one’s identity and past. JJ’s working-class background and her gender come up in her relationship with Thomas. Having described Thomas’s “Southern contempt for the working North”, JJ says, revealingly,

I have no doubt you looked at both “feminine” and “working class” as interchangeable and equally loathsome, and that it was a source of great eroticism for you to be taken by someone so debased …

We do not learn what it means to JJ to have been seen as “debased”. But it is implied that JJ also found great eroticism in the uneven power dynamics of their sexual relationship and in being viewed with contempt.

Read more: Novel that uses a transgender lens to explore our attitude to race

A novel of grief

As well as being a love story, At Certain Points We Touch is a novel about grief. Searching for Thomas in artefacts and surviving communications between the two of them, JJ says:

It feels especially cruel that when you died (when you went out like that – like a light), you didn’t take everything with you; you linger in your emails and your hand-scrawled notes. And what are we supposed to do now? All of this writing won’t turn the light back on.

It is a painful question, relatable to anyone who has experienced loss. Returning to the idea of this novel as “millennial”, it perhaps explores the unique characteristics of experiencing loss when online fragments of a person remain. Textual fragments and photographs can become an obsession – a way of piecing the person back together and hoping to make their death not real.

JJ’s reflection on Thomas’s death is particularly cutting, painful to read if you have lost a close friend or lover. The depiction of the physicality of loss makes it clear that Joseph has experienced the sort of all-consuming grief JJ describes:

The day I found out you were dead I wept like you can only weep once, doubled over in the emergency brace position, gasping for breath in between heaving sobs, dragging myself up to standing, clinging to the wall retching. And after that passed came the long slow blindsiding numbness, and then this desperation, almost a mania to see you again, which has never really gone away.

Towards the end of the novel, JJ explains why she created a written record of Thomas:

I know that just as memory is created by the act of remembering, so is the story created by the storytelling. From this point in time I’m seeking to represent the reality of a life (though not a death) I witnessed; but the wicked medium I’ve chosen, this narrative prose, has more power than me, the writer, and will go on to replace the reality it sought to represent.

JJ’s perspective as a writer reminds us of the record-keeping function of writing – that even without resorting to hagiography, writing about a loss keeps memory alive. While the novel is a love story, At Certain Points We Touch demonstrates how complicated the journey through grief is. It reveals that even in an emotionally complex, difficult relationship, loss can provide the ultimate illumination of personhood and identity.

Roz Bellamy does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.