Queen Charlotte captured viewers’ attention in the Netflix series Bridgerton as the snuff-sniffing, gossip-greedy, biracial wife of the “mad king” George III.

As the spin-off Queen Charlotte: A Bridgerton Story – billed as an “epic love story” – launches, just who was Charlotte? And why was she obsessed with Australia?

From German princess to British queen

Seventeen-year-old Princess Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz married George III in 1761, the year after his accession to the throne. She had been chosen, dispassionately, from a list of suitable wives for the young king.

Charlotte arrived in London from her northern German home speaking no English, though she would soon acquire it.

She brought with her a fascination of science – Charlotte adored botany – and the arts. A talented singer and harpsichord player, Charlotte would later be accompanied by a young Mozart.

She is also said to have brought the German tradition of the Christmas tree to Britain, with Queen Victoria making it popular.

Read more: A story of legends, families and capitalism: a candid history of the Christmas tree

Charlotte and George III’s marriage was a success. Contemporaries spoke of their devotion to each other, unlike other kings who strayed.

They had 15 children, 13 living to adulthood. Two sons – George IV and William IV – would later be king. Their granddaughter, Victoria, served as the longest-reigning British monarch.

Some thought Charlotte dull, preferring domestic life to court. Others called her power-hungry as George III suffered a series of bouts of mental illness, possibly caused by the blood disorder porphyria, though this is still debated.

More recently, Charlotte’s ancestry has been examined, sparked by her “African features” in portraits by Allan Ramsay. As fascinating as this is, more historians are sceptical of the claim that Charlotte was Black than support it.

Charlotte and the natural world

Across the 57 years that Charlotte was queen consort, Britain undertook an ambitious program to expand its empire and further knowledge of the natural world.

In 1768, seven years after Charlotte married into the royal family, George III commissioned James Cook with an ambitious voyage of discovery: to view the transit of Venus in Tahiti, then search the oceans for the “undiscovered southern land”.

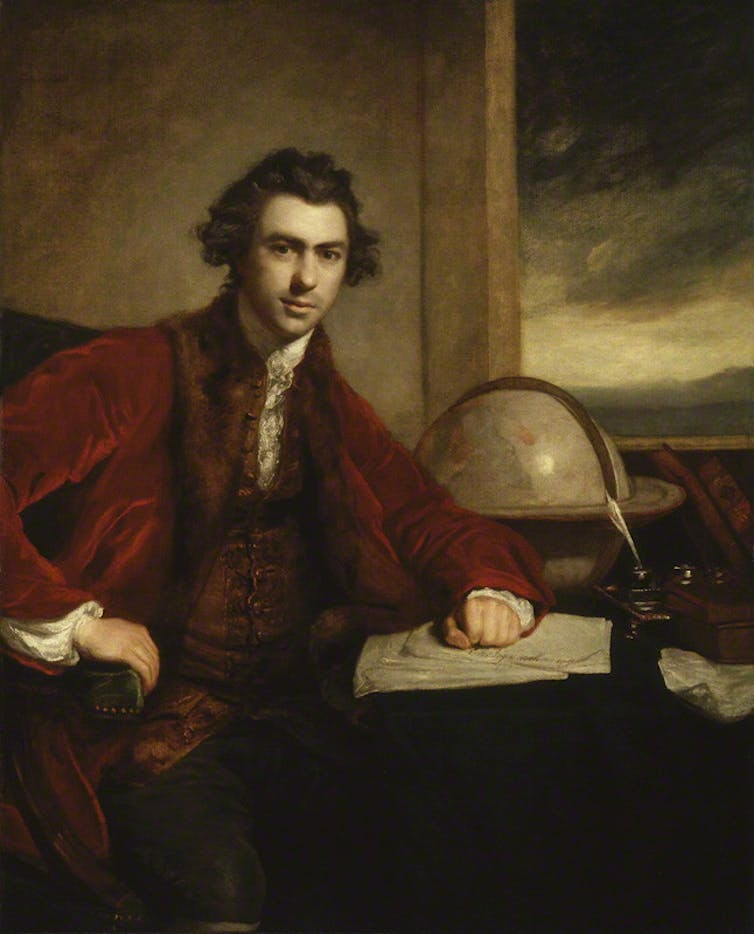

On a weather-beaten ship, Cook changed course to chart the eastern coastline of New Holland (Australia) in 1770. Across the four months that the Endeavour sailed up the coast, Joseph Banks – the naturalist and botanist who joined Cook’s voyage – collected plants and animals.

Banks returned to England with a staggering bounty of specimens, presenting them to Charlotte and George III shortly after. This launched the collection of Australian plants and animals across decades to follow.

Charlotte’s “cangaroos”

Charlotte penned an unusual passage in her diary in 1794. Describing some remarkable creatures that had been held beneath deck for months as they crossed the seas, then released into her menagerie, she wrote of glimpsing “the Young Cangeroo”.

“The Animal being of the Opossum kind Carries its Young in a Pouch”, Charlotte marvelled.

Banks and the Endeavour’s crew had been astonished from their first fleeting glimpse of the animals two decades earlier, likening them to greyhounds that flashed through the bush.

The kangaroos that later arrived in Britain alive – though many would not survive the crossing – symbolised power. They were coveted by the elite and other European rulers. Napoleon’s wife Josephine had kangaroos of her own.

Unlike anything seen before, Charlotte was awed by their tiny forelimbs and strong tail. She was fascinated by how kangaroos moved, hopping on their powerful hind legs.

She was especially intrigued by the kangaroo’s pouch. So were scientific men who studied the queen’s kangaroos, attempting to unravel the mystery of how they reproduced and cared for their young.

So successfully did Charlotte’s prized kangaroos breed that her flock grew to 20.

Charlotte’s Australian plants

As Charlotte’s kangaroos hopped through her menagerie, the neighbouring Royal Gardens at Kew became the storehouse for plants from across the empire.

Banks, then Kew’s de facto director, encouraged his global networks to collect for the queen. To the second New South Wales governor, John Hunter, Banks urged:

[…]when you make your excursions or when you send parties into new districts, you will not forget that Kew Garden is the first in Europe & that its Royal Master & Mistress never fail to receive personal satisfaction from every Plant introduced there from foreign parts.

The year before, Banks had assessed a remarkable herbarium offered to Charlotte that included rare Australian specimens. Amassed by French botanist Jacques Labillardière, then seized during the French Revolutionary Wars, the gift was not to be. Returned to Labillardière, he used the specimens to write the most comprehensive description of Australia’s flora.

Death of the queen

Charlotte remained queen until her death in 1818. It took months for the news to reach Australia.

When it did, the Hobart Town Gazette declared that Britain’s loss “will be not less felt in its remotest Dependencies”.

The settlement mourned Charlotte by firing guns, flying flags at half-mast and tolling church bells, though she had never set foot on Australian soil.

Lorinda Cramer receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.