Von Miller considers the fate of the modern-day pass rusher like a philosopher mulls the meaning of life. For the Bills’ sack master there’s not much difference, which is to say that Miller thinks about the purpose of his existence—dropping quarterbacks like bad habits—incessantly, in or out of season, awake or asleep, growing more obsessed each day.

Miller’s pass-rusher paradigm begins here: The vast majority of rushers must be tall enough to impede throwing lanes; strong enough to move massive men; patient enough to fail far more than they succeed; quick enough to thrive in slivers of time and space; athletic enough to change directions, deploy hands and bowl over and tug down targets. But that’s just the foundation. Even for the rare human who can do all those things, the baseline is no longer enough.

In the modern NFL, many rule changes—most, pass rushers argue—are designed to make the gig more arduous. The malicious intent with which, say, Lawrence Taylor once rocked quarterbacks is no longer permitted. Miller and his compatriots can’t hit too hard, too low, too high or too late. The NFL has made clear that it values its most glamorous position above all else. And in choosing pretty over gritty, the league also incentivized coaches to evolve offenses in ways that are increasingly unfriendly to pass rushers. Philosophies and schemes continue to widen (using more of the field) and tighten (shorter throws, delivered faster, more often). Coordinators weaponize timing and precision. All combine for optimum efficiency, further reducing those slivers of time and space available to Miller and his friends.

A typical sack, for instance, happens between 2.5 seconds and 3.2 seconds after the snap. That’s the window. The nature of any play, not to mention physics, makes arriving any earlier almost impossible. In most instances, any later means too late. As a response to the rule changes and offensive innovations, defensive coordinators have other players blitz less frequently, allowing more blockers to focus on pure rushers like Miller. They must, in their parlance, get home, with less help, in less time, every season.

Erick W. Rasco/Sports Illustrated

No wonder Miller, who has more career sacks (123.5) than any other active player, cannot stop contemplating. In an era that sees quarterbacks drop back more than ever before, the job of the pass rusher has never been more important—or more impossible.

The quarterback torturers are “genetic freaks,” per Miller, beefy and bendy bodybuilders who fly like hurdlers, only their obstacles are large, long and mobile. Modern rushers blend leverage, elite fast-twitch musculature, geometry, math, science, brute strength, biometrics, hand techniques, analytics, strategy and footwork. They’re a combination of wrestlers, movers, yogis, technicians, poker players, mixed martial artists, dancers, trapeze artists, magicians, decoys, data collectors and athletes. They operate alone or in groups of varying size. The best welcome double and triple teams as acceptable job hazards. And without them, NFL franchises have little hope to win Super Bowls. Which is why the 14 largest contracts next season will go to quarterbacks—and four of the 10 next largest will go to those who chase them.

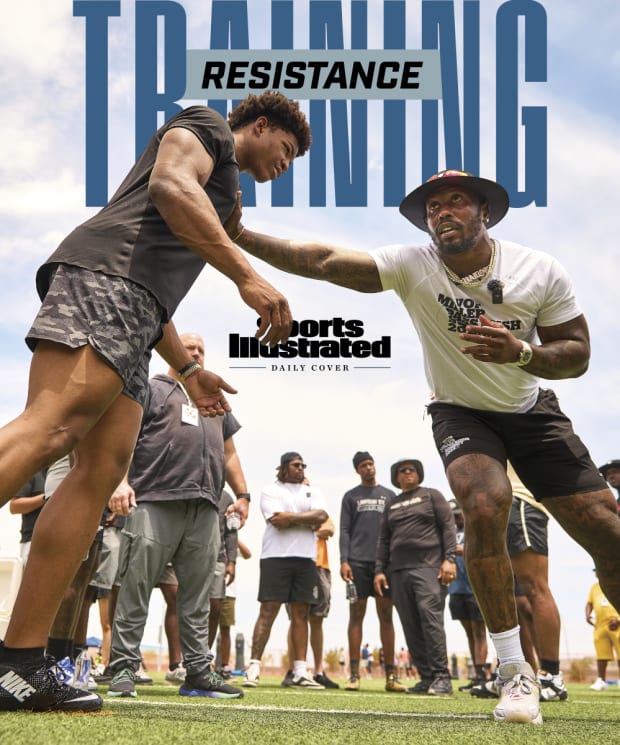

The resistance to the quarterback-friendly forces gathers near Las Vegas over two days in June, at the Von Miller Pass Rush Summit, where 30 pros immerse themselves in a sack incubator of sorts. They attend an informal mixer, train at a high school named Pinecrest Academy-Sloan Canyon, take turns leading film review sessions, trade tips and insight, firm up techniques, golf, gamble and drink. The experience, which Miller thought up seven years ago, is intended to close the gap between their mission and everything that threatens to unravel it. They’re here for their other team, and there’s only one requirement to join: They must hunt quarterbacks.

Hip-hop thumps at a headache-inducing volume as Raiders sack master Maxx Crosby rushes a drink cooler, wearing a black notorious hat, Marilyn Manson shorts and dozens of tattoos. Pass rushing, he says without hesitation, is “one of the most difficult and unique things in professional sports. It’s a science. But there’s an art to it.”

A few days before the summit, Miller joins a Zoom call. He’s in Colorado Springs, rehabbing his right knee, which he injured on Thanksgiving night against the Lions, and preparing for another comeback. Sweat drips down his face, fogging his glasses. His mind spins, thoughts bouncing and colliding, hands gesturing, words spilling forth. Conversing with Miller is like visiting a faraway galaxy. His brain is the most fascinating place in sports.

The idea for the summit surfaced in that beautiful mind after Miller won Super Bowl 50 with the Broncos and embarked on an offseason of self-discovery. While following Drake on tour a year later, an idea formed around the notion of craft. For Drake, creating was an existential exercise. And continuing to make music meant collecting and collaborating with distinct voices, elite producers and younger artists, high-end talents who might threaten other stars. To grow and evolve and remain on top, Drake needed the inspiration only those types could provide. “He was so open,” Miller says. “And it influenced his music.”

Miller wondered: Weren’t hit songs and QB hits similar—the results born from craft? Couldn’t he apply the same approach? He could, with an annual gathering meant to capture Drake’s spirit of collaboration and inspiration.

Miller modeled his new ambition on a Silicon Valley tech summit. He resolved to create an environment that encouraged myriad voices and fresh ideas. He sought football improvement but designed his summit, which debuted in 2017, for much more. He wanted brotherhood, camaraderie, trust born from vulnerability, connections that didn’t end when attendees flew home.

Aaron Donald participated some years, as did Khalil Mack, Chandler Jones, Arik Armstead, Myles Garrett, Shaq Barrett, Jeffery Simmons, Calais Campbell, DeForest Buckner, DeMarcus Ware, Bobby Wagner, Justin Houston, Dee Ford and Bradley Chubb. Joey Bosa joined the virtual, pandemic edition in 2020.

Miller and his support staff courted sponsors, coaxed coaches into joining, made rushers like Crosby, the Saints’ Cam Jordan and the Cowboys’ Micah Parsons—among them, that’s 303 career sacks—leaders at the event and continued to lobby those, like the Watt brothers, who had yet to attend. The vibe resembled the Pro Bowl, loose and relaxed but also a rare opp for the best NFL players to share among themselves. Miller believed in the idea so fiercely, he paid some expenses out of his own pocket.

At first, he imprinted his brand of pass rushing, centered on mindset. Miller views himself as an offensive player and opposing linemen as defenders. They must react to him. Sacks are his touchdowns; pressures, his completions; disruptions, more like first downs. Within that mental framework the scientist in him takes over, deploying a repertoire of moves—in search of sacks, of course, but also to collect data on everything from blockers’ hand/body/feet positioning to how they set up at the line to any tells. That information leads to adjustments, which is where the art comes in. Adjustments lead to dominance, and dominance leads to tweaks for the next week, so he can evolve beyond what opposing coordinators can glean about him from film study.

In recent years the summit has grown in the number of participants, the attention received and the value added. Over time, Miller came to understand that he benefited as much as anyone. It’s not his summit, Miller emphasizes; it’s theirs.

Outsiders might view stars from different teams sharing tips and goals as a competitive disadvantage. Miller never saw it that way. He argues that anyone immersed in a craft owes it to that craft to pass along what they can. This meant inviting not only new teammates (like when he joined the Bills before last season), but also rookies every year. The younger rushers have grown up in an era stuffed with elite camps and showcases. They’re accustomed to befriending rivals and swapping insights.

All learn, all benefit. But no two participants apply the lessons to the next season in precisely the same way. “I don’t have no secrets,” Miller says. “I don’t do anything special. I wish I had some sort of magic I could download on demand. The reason why it’s special”—he laughs—“is because it’s me.”

Erick W. Rasco/Sports Illustrated

On this Saturday under a cloudy desert sky, Dr. Miller, pass-rush scientist, wears both black (bucket hat, shorts) and white (T-shirt, socks, shoes). But what he hopes to impart this day is hardly that clearly divided. There’s a diamond-studded cross affixed to one tooth that gleams in the sun when he smiles. Bring on the nuance. That’s the point.

At 10:20 a.m., Miller gathers the class. “This,” he says to no one in particular, “is gonna be dope.”

He splits the group in half and dives right in, emphasizing “get off,” the first two steps after the snap. Those steps are critically important. The faster a rusher shoots forward, the sooner he reaches his destination. He also puts additional pressure on linemen, giving them more to worry about and less time to react. The key is footwork. Miller leans down to demonstrate, explaining why he prefers a three-point stance, meaning one arm and two legs planted on the ground. Crosby (12.5 sacks last year, eighth in the NFL) interjects, adding a tip—he prefers his feet planted closer together, for better balance and more push-off power.

Other players chime in with their personal preferences. Parsons (13.5 sacks in 2022, ranked seventh) tells the group he prefers a two-point stance. When he’s standing near the line of scrimmage he can move around, creating confusion among offensive linemen as they try to align their blocking assignments. He can also settle into the base angle he prefers—straight on, so “I can feel where they’re going,” he says.

“You can react faster,” Miller says, as Parsons nods.

The main speakers on this half of the field—Miller, Crosby, Parsons—segue into how to study offensive linemen. How blockers sit matters, for instance, whether leaned back (likely a pass upcoming) or forward (probably a run). But that’s the basic stuff, which the summit is intended to build on. Here, Crosby tells the pass rushers to examine the back of linemen’s heels. Are they planted (pass) or lifted (run)? Parsons steals glances at blockers’ heads. Are they looking downfield? Or at the ground?

This continues for more than three hours. Crosby details leverage (in general, low man always wins). Miller adds to that, demonstrating how to catch or strike away a lineman’s hands before they reach the rusher’s body. Miller notes one move he now prefers to avoid (the cross-chop, because it takes too long to use). But no matter how much time the players spend trading insider info and talking about the science of the pass rush, there remains the unteachable aspect: the art. “You really got to feel the game,” Parsons says.

“There’s no perfect pass rush,” Miller responds. “There’s no magic to it. The older I get, I’m a firm believer in get-off and adaptation.”

The craft immersion continues. How to sequence moves. Where to shoot dominant hands (just under the shoulder pads, at the chest). How linemen work together to create angles, openings and space in fractions of frenzied seconds.

Miller’s goal and Crosby’s words become clearer as the afternoon unspools. These rushers are brutes and thinkers, scientists and artists, dancers and weightlifters, athletes and adapters. Without this balance, the offense wins before most snaps. Throw in rule changes, schematic changes, officiating changes—and what becomes clearer and clearer is not why Miller has chosen to evolve his summit but why it matters, now more than ever.

Brian Rothmuller/Icon Sportswire/Getty Images

As the sun drops, the pass-rush party heads inside the school for a lunch break followed by afternoon film study. Various players have prepared to lead sessions lasting roughly 30 minutes each. Those who aren’t teaching sit behind desks, where they will spend three hours taking notes (phones, laptops, old-fashioned notepads), recording (phones), listening intently, nodding along or even (not naming names!) dozing off in Advanced Sack Class.

Miller stands before the group and riffs an overview without notes. He gestures at Jordan, noting how the two of them came into the league together in 2011 and became the preeminent pass rushers from that draft class—and how quickly that time went. He jokes about the 33-year-old Wagner’s advanced age and urges his compadres to ask questions, engage in sidebars and swap contact info. After all, this is their other team. “I want it all in the same pot,” he says. “I started this just for me to give back to the game. It’s an honor to play in the NFL. It’s an honor to have people ask me how I do it. It’s an honor to have this one day to share that with y’all, and it’s an honor to get yours, too.”

He smiles like the proudest parent at the playground, then resumes. It’s about like-minded guys. Pass rushers. Who we are. And what we do.

“Now,” Miller says, “I got one of my favorite guys in the league, I’ve known this guy forever, Maxx Crosby, Mr. Vegas, give him a hand!”

Crosby walks to the front of the room for a mic check, having fashioned his presentation in advance. What matters once the lights dim and the projection screen lights up is what summit attendees do with the valuable insight from peers. He jokes about becoming a pass rusher because he had zero other career options. Then he asks: How will they take his 30 minutes and apply it?

The odds are not in their favor. Say the opposing offense runs 60 plays in a game. Maybe they run the ball 20 to 25 times that day. The rest are passes, but many are designed to be thrown before there’s a chance to reach the QB, while others become scrambles or audibles. Most weeks, Crosby tells the audience, they might get 10 clean rushes. Might. To close the gap, every attempt matters.

He shows a clip from Week 18, against the Chiefs, explains the game situation and his thought process in the moment, leading into his deployment of an Allen Iverson–like jab step deep into a game the Raiders, at that point, had little chance to win.

“Why wouldn’t you just do it earlier?” Miller asks.

That’s the art. Crosby spent much of that afternoon doing something similar to what boxers do in the early rounds of a fight. For him, every speed-to-power move is like a jab to gauge and create distance between him and his opponent. He doesn’t use his version of power punches until he has the distance calibrated and space available to make his attack most effective. Otherwise, what’s the point?

“Which step is best to jab on?” someone else asks.

“Usually the third,” Crosby notes. But not always, because the jab must come before contact, or the opposing linemen can tie up Crosby.

At the end of his Maxx Talk, Professor Crosby says, “We grow every single time we do this. As long as we do the follow-up and put the time in.”

“It’s the mindset,” Miller says, “of owning the game.”

He mentions times last season when, while preparing for a specific opponent that Crosby or Jordan had already faced, he would call to exchange ideas and information and get the download.

“It’s like the Legion of Doom,” Miller says. “This guy is robbing banks. This guy is destroying planets. They put all their ideas into a Google doc”—editor’s note: not actually true, but the sentiment holds—“and see how they can be even more [dangerous and effective].”

Brace Hemmelgarn/USA TODAY Sports

Around sunset, Miller and his merry band of sackers hop onto a shuttle that’s comically compact relative to the size of its passengers. It’s a short drive to the M hotel, where Miller hops off and heads upstairs to his apartment-sized suite for the weekend. Inside Room 9150, with The Strip blinking in the distance, he reclines in a chair, sips from a plastic cup and turns to the concept that ties everything together. Legacy.

Miller’s may well be carried on by players like Nolan Smith, the edge rusher from Georgia who, like Miller, trains at Proactive Sports Performance in Westlake Village, Calif. Smith went 30th to the Eagles in the NFL draft. Soon afterward, he connected with Miller, who invited him to Nevada—in this world, akin to a golden ticket—by centering his pitch on the football gods both needed to appease.

Ware, who retired in 2017 and is ninth on the all-time list with 138.5 sacks, mentored Miller in a similar way. Miller has built out his sack village while winning Defensive Rookie of the Year, two championships and a Super Bowl MVP, becoming a perennial Pro Bowler and sometimes All-Pro and carving out a near-certain Hall of Fame career.

Over the past seven years, the summit has evolved as Miller has, from a young, self-professed knucklehead into a wise mentor bent on doing right by the football gods. He never thought his creation would spawn imitators, but it did, from Tight End U (run by George Kittle, Travis Kelce and Greg Olsen) to OL Masterminds (run by All-Pro tackle Lane Johnson and O-line guru Duke Manyweather) to informal gatherings of elite players in other position groups. Now Miller plans to expand the summit in future offseasons. He will rebrand and assume less of a forward-facing role, but not because of time constraints nor costs. The ambition simply grew too large and too critical for one, even broad-shouldered, man to carry alone. The rebrand will include a name without “Von Miller” in the title.

Smith understands Miller’s intentions now. He already knew that the way many viewed their craft—see quarterback, reach quarterback, hit quarterback—was overly simplistic. Even so, he never could have imagined the ocean of nuance, science and art that has pushed Miller to 19th and climbing on the all-time sack list. Greatness lies within embracing those notions.

Young players often wonder whether the day will unlock secrets known to only an exclusive fraternity, a pass-rushing version of The Skulls. Smith learned that such secrets do not exist, while adding other lessons he will carry into next season and future seasons. He cannot overstate the value in that. About those football gods, he says, “Boy, do I believe in them.”

Take that, officials, quarterbacks, coordinators and league rule shapers! Every change and tweak and piece of those ongoing evolutions gave large men with uncommon speed and agility a purpose they weren’t likely to find in as much depth otherwise. That’s good news for the sack masters and bad news for the sackees.

Back in the hotel suite, Miller begins to wonder once more. His football legacy was secured long ago, but what he wants that legacy to look like, to be, might focus as much on the summit as the sacks. Maybe even more. “I genuinely feel like this will outlive us,” he says. “We will continue to change the young-pass-rushers model. It’s not the Von Miller summit. Anybody that’s rushing the passer, it’s for us.”