There was a time when the Giro d'Italia did gentle introductions. In generations past, the opening road stage often amounted to a relatively forgiving procession before a late injection of pace and an inevitable bunch finish.

The fast men jousted for the first maglia rosa of the race, while everybody else enjoyed a largely untroubled afternoon as they set out on their three-week endeavour. There was something of a quid pro quo, in other words. A pink jersey for a sprinter and one day less for everybody else.

Over the past decade, in the Giro and elsewhere, the game has changed considerably. As last year's high-octane opening to the Tour de France in the Basque Country demonstrated, GC riders are expected to hit the ground running at Grand Tours these days, and the route of the 2024 Giro d'Italia hammers home that concept to the nth degree.

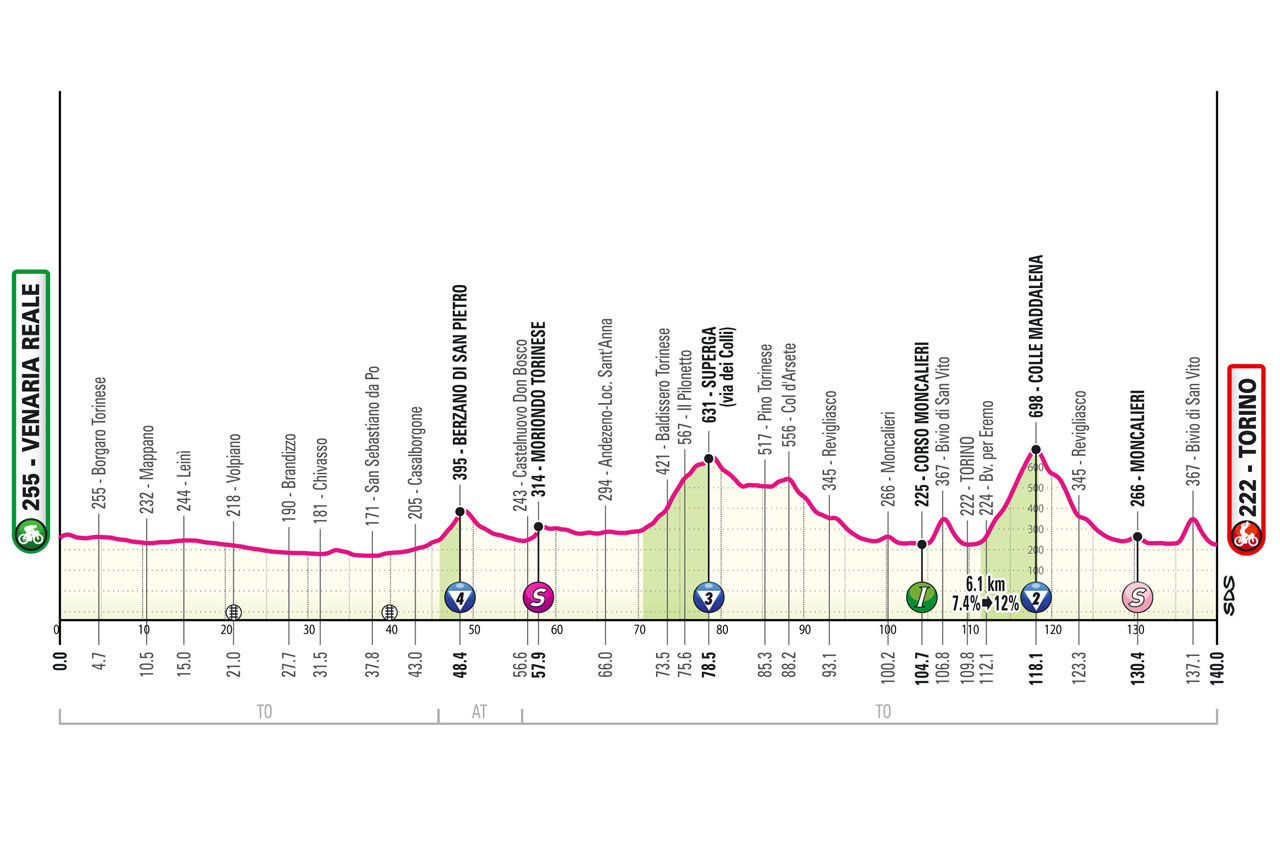

The summit finish atop Oropa on stage 2 draws the eye, of course, but the difficulty of Saturday's opener around Turin is not to be overlooked. The combination of a short stage (140km) and punchy climbs (Superga, the Colle Maddalena and Bivio di San Vito) could add up to a most explosive start to the race, particularly if Tadej Pogačar sets out here still stuck on his default settings from the Spring.

In Turin's Egyptian Museum on Thursday morning, a small ceremony was held ahead of the Grande Partenza. The museum, which houses the most significant Egyptological collection outside of Cairo, is Turin's most visited tourist site and it celebrates its 200th anniversary this year. To mark the occasion, the winner of Saturday's opening stage will be presented with a reproduction of the shebyu collar of Kha, an architect who supervised tomb-building in the Valley of the Kings.

It may well prove, of course, that the recipient of Kha's collar in Turin on Saturday afternoon will be the same man lifting the Trofeo Senza Fine of overall victor in Rome on May 26. For Pogačar, the overwhelming favourite for this Giro and a rider of seemingly insatiable appetite, the opening weekend offers an early chance to sink some very firm foundations atop the overall standings.

The Slovenian had no qualms about running up the score wherever he could at the Volta a Catalunya in March, after all, and his track record at the Tour suggests that he is unlikely to sit on his hands and wait for the third week to put his stamp on this race. The climb of Oropa looks to be the obvious place for Pogačar to seize control of his Giro debut, but the punchy nature of Saturday's opening act raises the prospect of a rider leading the race from start to finish, a feat last achieved by Gianni Bugno in 1990.

Indeed, the feat seems likelier now than when the Giro route was first unveiled in October. Back then, the published profile of stage 1 suggested a flat 20km run-in from the base of the Maddalena to the finish on the banks of the Po. In the Spring, however, some eagle-eyed observers noticed a tweak on the profile that featured on the Giro website, with the unclassified kick up the Bivio di San Vito a late addition, just 3km from the finish. A stage that had looked destined to produce a reduced bunch sprint during October's presentation suddenly had a Pogačar-friendly springboard in the finale.

Race director Mauro Vegni insisted that the alteration had been made during a routine course inspection in November and hadn't been publicised by RCS Sport as it "wasn't that relevant." Vegni went on to downplay the ascent as a mere "zampellotto," an expression coined by the journalist Gianni Brera in the 1960s to describe a climb scarcely worthy of the title.

For the 2024 iteration of Pogačar, however, a zampellotto might be all he needs.

When Pogačar sat down to meet the press on Thursday afternoon, he wearily downplayed the idea that wearing the maglia rosa for three whole weeks was an objective, and yet he didn't entirely rule out the prospect of an early offensive at this Giro either.

"It's not something that's a big goal," Pogačar said of taking pink in Turin. "It needs to be in Rome, it doesn't need to be the first day. We'll go day by day and see how the legs are. If there's an opportunity to take the win or the pink jersey, you'll take it, but we need to play it smart during the Giro."

Turin

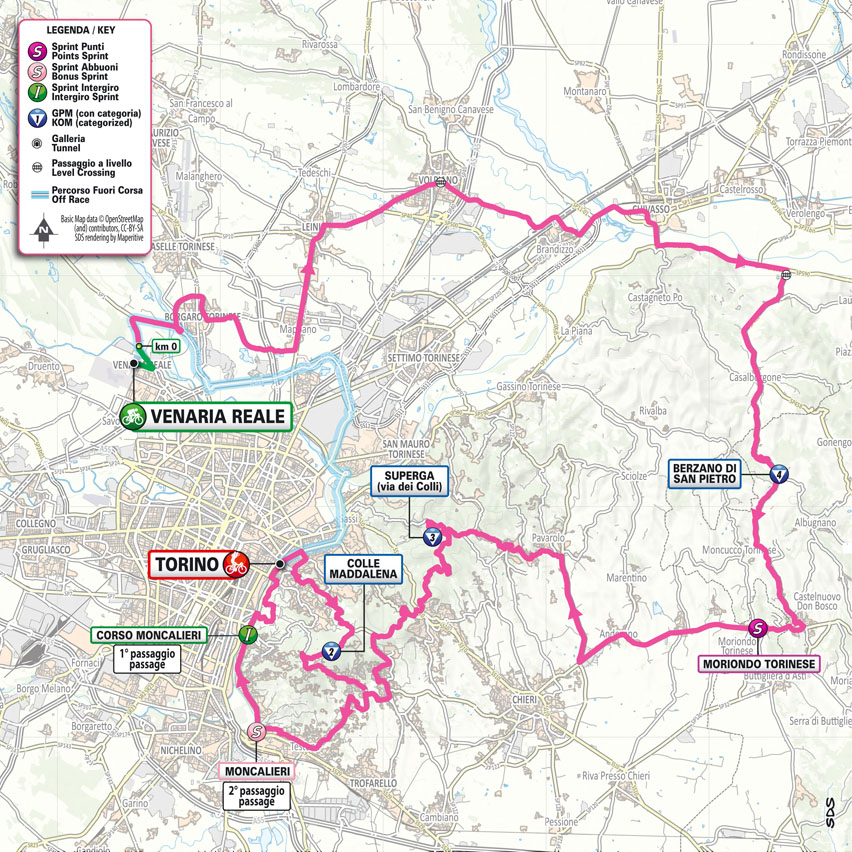

As in 2011, when the Giro marked the 150th anniversary of Italian unity, this year's race gets underway just north of Turin in Venaria Reale, site of a former residence of the Royal House of Savoy. Venaria served as their base for hunting expeditions in the rolling hills north of Turin, but the meat of Saturday's stage is focused on the more demanding terrain southeast of the city in the Parco Naturale della Collina Torinese.

The terrain is familiar from the Milan-Torino of years gone by and from the most breathless stage of the 2022 Giro when Bora-Hansgrohe shook a hitherto staid race from its torpor with an all-out assault over Superga and the Colle Maddalena. On that occasion, the race tackled the climbs twice and the bunch splintered accordingly. This time, a fresh peloton should prove rather more resistant to this reduced diet of climbing, but the front group will still be a small one come the finish on the banks of the Po.

The first climb of the Giro is category 4 Berzano di San Pietro after 48km, but the race should truly ignite 30km or so later on the category 3 ascent of Superga, which also serves as the emotional centrepiece of the stage. The mountain, with its Filippo Juvarra-designed basilica at the summit, is more than a visual signpost for the city below, it is also the repository of a part of its soul.

On May 4, 1949, the dominant Torino football team of the era – known to all as Il Grande Torino – perished when their plane crashed into a supporting wall of the basilica. The opening day of the Giro marks the 75th anniversary of the air disaster, in which 31 people lost their lives. A poignant memorial stands behind the basilica, and the Giro will pay its own tribute when the race passes.

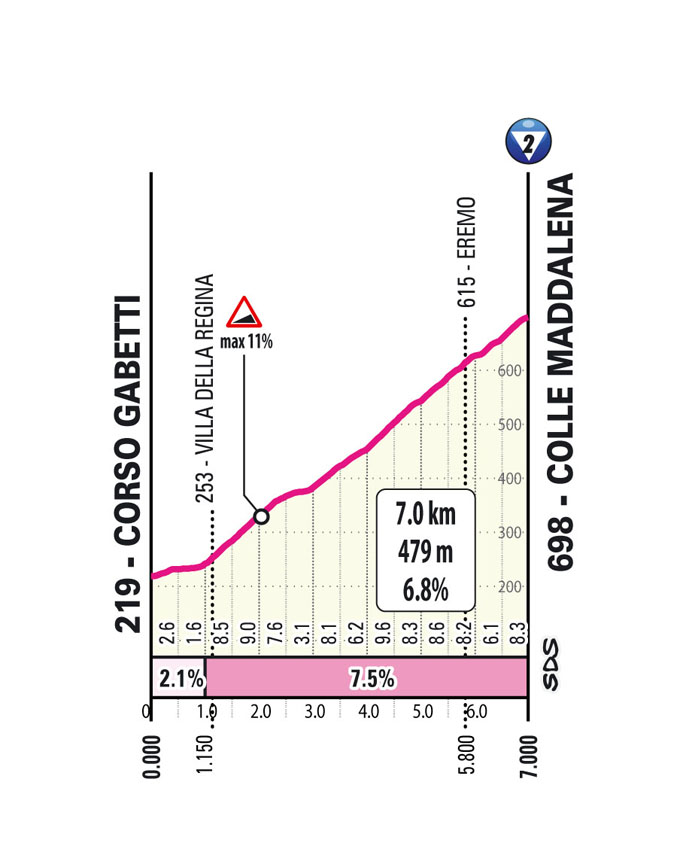

After descending to Turin and crossing the finish line for the first time, the peloton must scale the category 2 Colle Maddalena, which climbs for 7km at 6.8% and features pitches of 12%. The ascent of Superga is tackled via its gentler approach, but there are few concessions to the non-climbers on the Maddalena. Eddie Dunbar (Jayco-Alula) reckons that there will be no more than 30 or 40 riders left in contention after those climbs, but it remains to be seen if the San Vito whittles that group down still further.

Beyond Pogačar, riders like Julian Alaphilippe (Soudal-QuickStep), Romain Bardet (DSM-Firmenich-PostNL), Daniel Martínez (Bora-Hansgrohe) and Aurélien Paret-Peintre (Decathlon-AG2R) might also be to the fore on the kick up the San Vito.

The fast men, on the other hand, have all but resigned themselves to their fate here. Even Laurence Pithie (Groupama-FDJ), the sprinter best equipped to cope with climbs on this Giro, suspects that the addition of the San Vito has effectively ended his hopes of wearing the maglia rosa in Turin.

"With the original plan, I definitely would have been going for it and had that as a big goal, but I think it could be too hard for me now with the new finish," Pithie said in Turin on Thursday. "If Tadej wants to make the race hard, I don't think I'll be there anymore."

Oropa

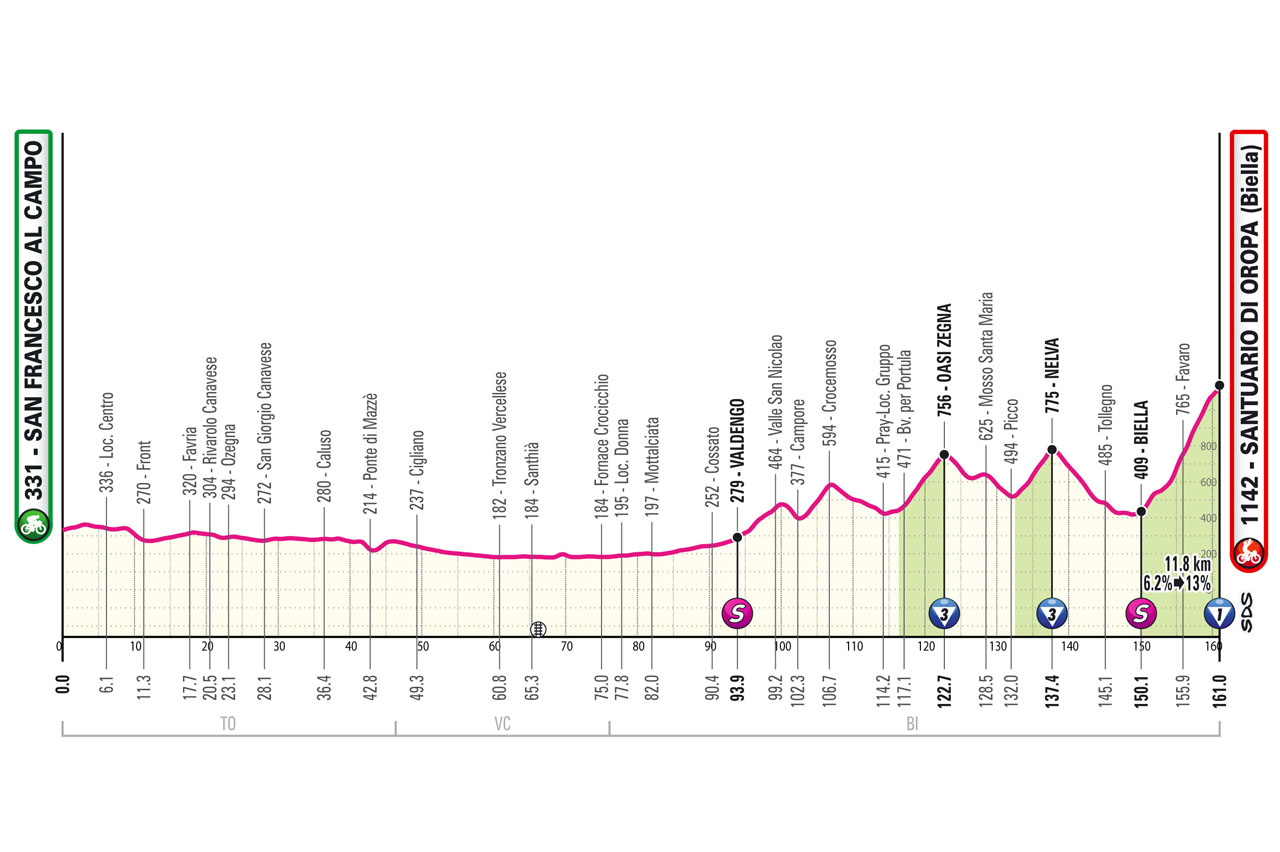

If the opening stage is a matter of interpretation, then the second day of the Giro looks to be rather more straightforward. The 161km run from San Francesco al Campo is punctuated by the category 3 climbs of Oasi Zegna and Nelva, but the day can ultimately be distilled to the final, category 1 haul up Oropa.

The 11km ascent is far from the most demanding at this Giro, but it's made a difference in years past. In 1993, Piotr Ugrumov briefly had Miguel Induráin himself against the ropes on its slopes. In 1999, the late Marco Pantani unshipped his chain at the base of the climb and then zoomed past no fewer than 49 riders en route to stage victory. On the Giro's last visit in 2017, Tom Dumoulin found attack to be the best form of defence when he surprised the pure climbers with a late acceleration.

On those occasions, mind, Oropa came in the latter part of the Giro. This time out, the GC contenders hit the ascent from something close to a standing start. There hasn't been a summit finish at the Giro this early since 1989 when Acácio da Silva atop Mount Etna. The volcano, as recent editions of the Giro have repeatedly shown, is an amenable sort of climb, with relatively little separation among the contenders at the summit.

The ascent of Oropa, on the other hand, should do more than simply rearrange the furniture of this Giro. A rider like Geraint Thomas (Ineos Grenadiers), whose build-up to this Giro has been rather steadier than Pogačar's, can't afford to be caught flat-footed here.

The stage has the potential to leave a lasting impact on the entire architecture of the race, especially if Pogačar travels at the kind of warp speed he produced at Catalunya and Liège-Bastogne-Liège. "The GC won't be won on the first two days," Dunbar said. "But if you have a bad day, you could be a minute or two down on GC."

No, for better or for worse, the Giro doesn't do gentle introductions anymore.