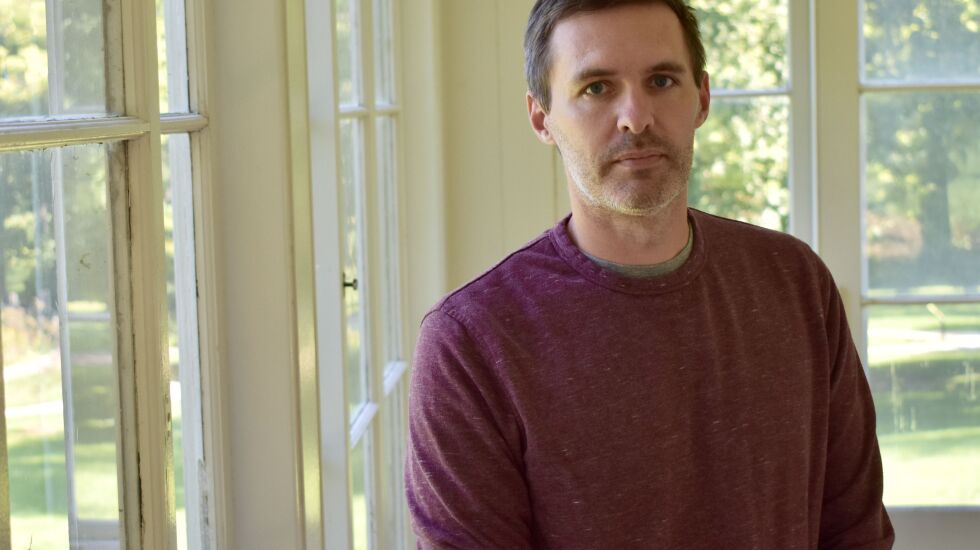

Jordan Esparza-Kelley switched schools in third grade when his family briefly moved from Waukegan to neighboring Gurnee.

The move was only a few miles, but the educational gap was expansive.

“In Waukegan, we had this computer teacher who would wheel around this cart of old laptops for tech class like twice a week,” Esparza-Kelley said. “In Gurnee, I walk in and there’s a gigantic computer lab with like 45 brand new Macs in there.

“Going from that school [in Waukegan] to the one in Gurnee and seeing what they had — insane. It’s like a shock.”

That disparity in resources for Waukegan — the majority-Latino seat of mostly white Lake County — hasn’t lessened much in the years since, by the 26-year-old photographer’s estimation.

And it’ll still be on his mind when he heads to the ballot box for November’s midterm election.

“This is a city with a heavy first-generation, second-generation immigrant population, a heavy Black population, and both of these communities historically have been economically sanctioned almost, with the lack of opportunity for schools and things like that,” Esparza-Kelley said of his hometown.

“So it’s not just, oh, do this, vote this way, and boom, now we’re good. We need leaders who take a macro vision.”

He’s among many Waukeganites who say they want public officials to take a holistic approach to the problems facing their lakefront city 40 miles north of Chicago.

The Sun-Times talked to dozens of likely voters in Waukegan to get an idea of what issues will guide their vote in the Nov. 8 election, and their concerns are likely familiar to most urban dwellers — rising crime, inflation, opioid addiction, affordable housing and more.

But residents say those problems are especially acute in a city of color that’s home to more than 89,000 people, where the median household income is about 40% lower than across Lake County at large.

And while many politicians go out of their way to campaign in Waukegan and talk about those issues, residents say they’ve seen few follow through with tangible results.

“Everybody wants the minority vote, but nobody’s contributing to minority communities,” Esparza-Kelley said, outlining a desire to see greater investments in school buildings, scholarship opportunities and business incubators.

Like most of the people who shared their thoughts with the Sun-Times, Esparza-Kelley said he doesn’t identify completely with either of the major political parties but acknowledged he generally votes for Democrats.

For some in the reliably blue city — President Joe Biden won most Waukegan precincts in 2020 by margins of 60 percentage points or more — the polarization in national politics has made their own party lines more pronounced.

“We have Republican leaders who are saying they’ll question the outcomes of elections if they don’t win,” Adam Carson said at his coffee shop, Drip & Culture. “If we can’t trust the outcome of our elections, we no longer have a democracy. That’s approaching dictatorship.

“So yes, I’m going to vote for Democrats who aren’t spreading this scary wave of misinformation,” he said.

Carson, 41, opened Drip & Culture early last year at 2015 Grand Ave., with the tag line of “Socially Minded Coffee.”

“Not a smart business decision,” he said with a laugh. “We want to run the type of business that leads with our values first.”

Those values include acknowledging America’s ongoing history of racism, addressing disinvestment in Black and Brown communities and promoting immigration rights, Carson said.

“We want our community to be as welcoming as possible,” he said.

Waukegan has a long history of welcoming new arrivals.

An extensive line of Native American groups had called the lakefront land home over thousands of years by the time French explorers Jacques Marquette and Louis Joliet met the Potawatomi there in 1673, according to Ty Rohrer, the Waukegan Park District’s manager of cultural arts.

The thriving French fur trading post — named Waukegan as a variation on the Potawatomi word for “fort” — eventually gave way to other white settlers and federal officials who strong-armed the land from Native Americans in 1829.

The harbor city, formally incorporated in 1859, was an agricultural hub by water and later by rail, shipping grain and produce across the region. Population boomed with industrialization as workers flocked to Waukegan’s flour mills, shipping yards and other manufacturing plants.

The city was also a well-traveled stop on the Underground Railroad, with Waukegan abolitionists shepherding many from slavery before the Civil War. By the 1920s, an exodus of African Americans from the South followed the industrial jobs to the city, which also saw an influx of residents from Mexico and Puerto Rico.

“It’s always been kind of a safe haven here,” Rohrer said.

Today, about 52% of Waukeganites identify as Latino, 20% as Black, 19% as white and 6% as Asian, according to the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning.

But with thousands of manufacturing jobs disappearing over the past few decades, Waukegan has seen more than 100 years of steady population growth sputter in the 21st century. And the median household income is less than $54,000, compared to the countywide median of almost $93,000.

Residents say it comes down to a lack of opportunity, often early in life — and it’s something they want to see addressed by elected officials.

“It starts in schools,” Vanessa Lopez, a hospice nurse, said while walking her chihuahua Hugo downtown. “It just seems like they don’t have the funding for the extracurricular activities to give kids something to do and to hope for and keep them off the street.”

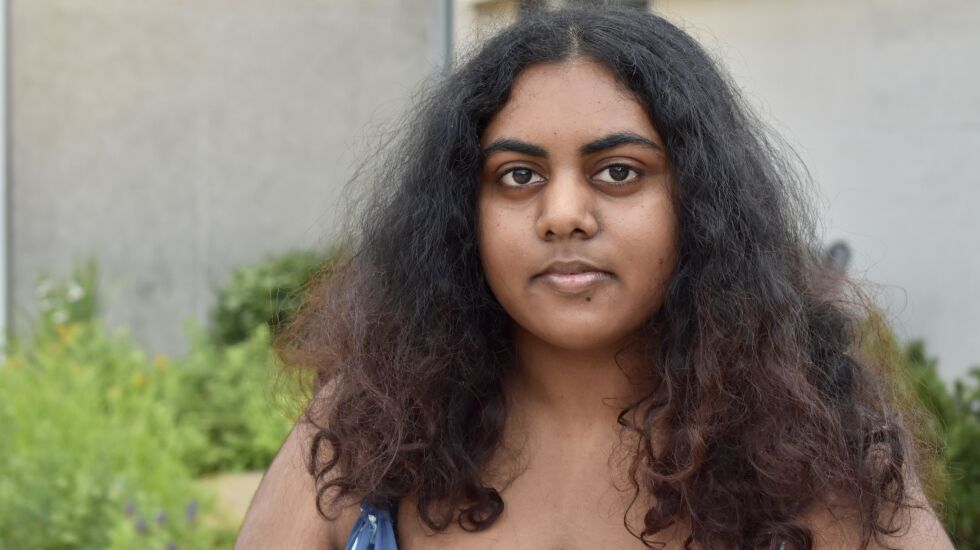

Jacqueline Moore, 24, said she’d vote for candidates who not only would increase education funding but who would promote career paths outside the usual route.

“I thought the only way to become successful is college, but there’s entrepreneurship, trades, and I think we need to branch out with those more to give kids more options,” Moore said after a study session at the Waukegan Public Library. She’s working toward a marketing degree at Columbia College Chicago.

“For minority groups in low-income cities like this, that would be huge,” she said.

Absent those opportunities, many residents say they’ve seen a rise in crime, violence and drug addiction, much of it related to gangs — and all of it exacerbated by the pandemic.

“It seems like we’re having a lot more violence in Waukegan where we didn’t have it a few years ago,” said Evelyn Edwards, 57. She said she wants to see officials tamp down on the crime but hailed Democrats who have championed drug court and other treatment-based alternatives to the criminal justice system for people struggling with addiction.

“I vote for people who have a heart when it comes to those things,” Edwards said.

So does Mary Byas, a crossing guard at Glen Flora Elementary School.

“I’ll vote for people putting money into housing for senior citizens and people with disabilities,” said Byas, 63. “It’s getting harder and harder for people to get by.”

Waukegan Mayor Ann Taylor said the pandemic-powered punch of inflation can be seen in her city’s food pantries, which are serving the most people they’ve seen per day in years.

“People were already living paycheck to paycheck, and now more is being taken from each check,” said Taylor, who became the first woman to lead the city when she won the municipal election as an independent in 2021.

Despite growing pains as Waukegan stretches toward a more tech-based economy and away from its industrial past, Taylor said there’s still optimism in the city.

“This is a place to start businesses. We’ve always had that entrepreneur spirit,” Taylor said.

Waukegan voters’ concerns also cycle up to the nation’s volatile political climate.

“It’s ‘Fahrenheit 451’ come to life,” said Priscilla Nabors, 65.

That was a reference to the famed dystopian novel of the most famous writer to come out of Waukegan, Ray Bradbury — and to a growing nationwide trend of conservative school districts trying to ban books with provocative themes.

“We should be putting more books into schools, not taking them out,” Nabors said.

The same goes for abortion. Waukegan’s Planned Parenthood clinic is certain to see an influx of patients seeking care from just across the border in Wisconsin, where the treatment has been mostly banned.

“I never thought the right to choose would be something that I’d have to weigh in my vote, but here we are. I took that for granted,” said Margot Gillin, a teacher in the city’s public school district. “That’s a choice we cannot let slip away.”

“It’s scary, the way the conversation has been going,” Carol Freitas said over dinner with her colleague, Gillin. “It’s just all Trump and Biden and doom and gloom.”

Two names that don’t often come up naturally in conversation among Waukeganites? Darren Bailey or J.B. Pritzker.

Of more than 50 people the Sun-Times talked to in Waukegan’s central business district, near its municipal beach and in scenic Bowen Park, only about a quarter were aware the Republican Bailey was running to unseat the sitting Democratic governor.

Those who recognized Bailey’s name didn’t know much about his platform beyond his support for former President Donald Trump. Only two suggested the downstate farmer would have their vote.

“Democrats haven’t done s— for this city,” said Paul Krebka, one of those rare Waukeganite Bailey supporters. “We could use some change.”

There wasn’t a Bailey campaign sign to be found along a few of the city’s main thoroughfares on a mid-September afternoon. Nor were there many placards for Pritzker, who certainly isn’t gearing up for much of a challenge in the far north suburb. The billionaire Democrat swept the city’s precincts — most with 70% of the vote or more — when he beat Republican ex-Gov. Bruce Rauner in 2018.

About half of Waukeganites who took part in the Sun-Times’ highly unscientific poll said they were undecided on the governor’s race, with most of those saying they haven’t even started thinking about their November ballot.

The vast majority of the remaining half said they’d probably vote for Pritzker, but not all of them were enamored with the incumbent Democrat’s first term.

“Legalizing weed was cool, but then they totally shut out communities of color,” graphic designer Yesenia Bareles, 36, said of the state’s botched launch of the legal cannabis industry. Black and Brown entrepreneurs were essentially locked out of the business until earlier this summer.

Pritzker’s COVID-19 shutdowns didn’t go over well with some, either.

“I thought that was an overreaction,” Erick Sanchez said, taking a break from skateboarding near Bowen Park to chat with a reporter.

But he’ll still probably vote for Pritzker, he said. And if he doesn’t, he thinks most other Waukeganites likely will.

“Most people are working and don’t have the time to do all the research,” Sanchez said. “You pretty much know how things are gonna go around here.”