FREEPORT, Ill. — The Halloween decorations are staying up a little longer this year outside Patty Tricker’s Freeport home.

Among the ghouls, clowns and other frights haunting her front yard — a yearly attraction in this northwestern Illinois city of 24,000 — Tricker’s newest installation features a dummy of President Joe Biden with a tube connecting his head to an ominous laboratory staffed by a straitjacketed Nancy Pelosi.

“And he’s put up two white flags because he’s surrendering to everything that is not good for the nation,” the aptly named Tricker explained during a break in the treat-serving action on Halloween.

Dozens of trick-or-treating families filed past the elaborate display a week ahead of election day — not all of them completely clear on the concept — but the vast majority cracking grins at the provocative setup.

“We’re going to leave this up until after the elections are over because people need to vote,” said Tricker, who described herself as a proud Republican. “And if they need to see something silly, that grabs their attention — I don’t care if it makes them vote.”

Her Biden brain-leaching exhibit is all in cartoonish fun, but Tricker said Democratic policies should spark real fear.

“They’re all too happy to let criminals roam free,” she said.

She’s among many Freeport residents on either side of the aisle who say they’re frightened by what the future holds if it’s in the hands of the opposing party — especially as this once-booming manufacturing town two hours northwest of Chicago finds itself at a crossroads, grasping for a new economic identity.

The Sun-Times spoke with dozens of Freeporters to gauge the issues on their minds heading into Tuesday’s midterm election, and their responses were fittingly diverse for a blue-leaning city that serves as the seat of blood-red Stephenson County.

LaRhonda Jones and Tanisha McKenzie are on the opposite end of the political spectrum from Tricker, but they had a hoot over her Halloween spectacle as they made their way through the neighborhood with their families.

“Everyone’s got a right to their opinion,” said Jones, 28.

She said she plans to vote for Democratic lawmakers, who she thinks are more likely to support after-school programs and child-care resources that she finds lacking in Freeport.

“We need productive things to occupy our kids not only for them but so that we [parents] can go out and make more money to provide,” Jones said.

McKenzie, 40, still enjoyed Tricker’s decor, too, though she wasn’t as entertained by the crosses on the lawn that represent aborted fetuses.

McKenzie said her Democratic vote was secured this summer with the U.S. Supreme Court’s overturning of the Roe v. Wade decision, which had protected abortion rights at the federal level for half a century.

“If my 16-year-old gets pregnant, I want her to have a choice in how the rest of her life goes,” McKenzie said.

‘Losing my country a little bit’

Such diverging viewpoints aren’t uncommon in Freeport.

Democratic Gov. J.B. Pritzker won in 11 of 18 city precincts during his successful 2018 bid to unseat GOP former Gov. Bruce Rauner — and Biden took all but three Freeport precincts when he beat former President Donald Trump in 2020.

But the margins weren’t overwhelming for either of those Democratic leaders, and they were both wiped out across the rest of mostly rural, solidly Republican Stephenson County.

That split was evident in a highly unscientific poll of the 30 Freeporters who shared their thoughts with the Sun-Times over the past week. Twelve said they’d vote for Pritzker compared to 11 for his GOP challenger, state Sen. Darren Bailey of downstate Xenia. The rest said they weren’t sure.

Jeffery Wall, who co-owns the Wall of Yarn knitting shop with his husband in downtown Freeport, said it’s sometimes uncomfortable being in a liberal bubble, “surrounded by Republicans, some of them a little more extreme than others.”

No matter the party, Wall is sick of the polarizing tone of election season.

“It’s always just bashing the other guy. Everything’s just attack, attack, attack and not really addressing the big issues,” such as climate change, Wall said.

Gary Jakubowski said he’s most worried about the vitriol he hears coming from one side: “Donald Trump and the right-wingers.”

The 65-year-old, who retired in Freeport after a career on Chicago’s trucking docks, described himself as a Reagan Democrat whose party identity has crystalized in response to Trump’s persistent lies about fraud in the 2020 election.

“It feels like I’m losing my country a little bit,” Jakubowski said after stopping at an ATM in downtown Freeport. “It’s un-American. It’s scary.”

‘They’re not working for us’

But Danielle McKee said she has serious concerns about voter fraud in the midterms despite the fact authorities haven’t found any credible evidence of electoral chicanery.

Higher on her list of priorities, though, is school safety. Amid a nationwide rash of school shootings, McKee said she wants armed guards posted up inside all school buildings.

“I think our schools need to be armed like this courthouse because the kids are our future,” she said while stopping for a chat outside the Stephenson County courthouse.

The 35-year-old office secretary said she was a registered Democrat but that, over the past decade, “It feels like the Democratic Party is literally trying to take down the country” with policies she thinks go too easy on criminals and too hard on small business owners.

“They’re not working for us. They’re working for themselves,” said McKee, who now mostly votes Republican but identifies as an independent. “My taxes just keep going up, and I just keep making less.”

As a result, McKee said she and her family plan to leave Illinois within the next few years.

That would mark another Freeport exodus in what has become a painfully familiar pattern for the city over the past four decades. The population has shrunk about 15% since topping out at nearly 28,000 in 1970, the unforgiving aftermath of an economic transition that has seen thousands manufacturing jobs lost to cheaper competition overseas.

From ‘free port’ to ‘Pretzel City, U.S.A.’

Workers once flocked to the rolling hills of Freeport, which for generations served as a key Midwestern rail hub.

Several Native American groups had called the land along the Pecatonica River home for at least a millennium by the time white settlers arrived in the 1830s at the trading post originally named for Winneshiek, a Winnebago chief.

Pioneer and trader William “Tutty” Baker operated a ferry helping new arrivals cross the river at no cost, which, legend has it, prompted his exasperated wife to wonder aloud why they didn’t just call it a “free port.”

German settlers made up the bulk of the population as the city was incorporated in 1855, bringing with them the beer and bakeries that would help earn the city its moniker of “Pretzel City, U.S.A.” A term that had been considered mildly derogatory for Germans was turned into a badge of honor. Freeport High School is still “Home of the Pretzels.”

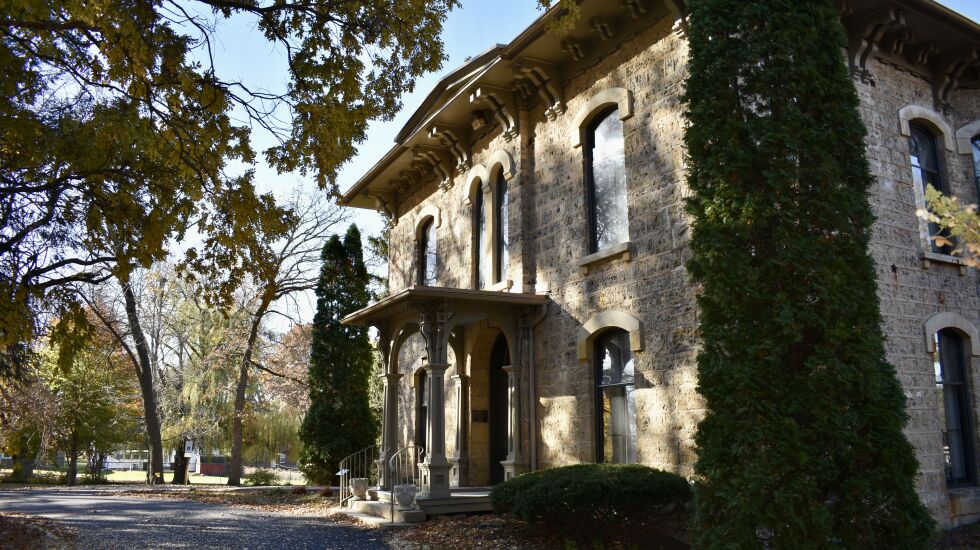

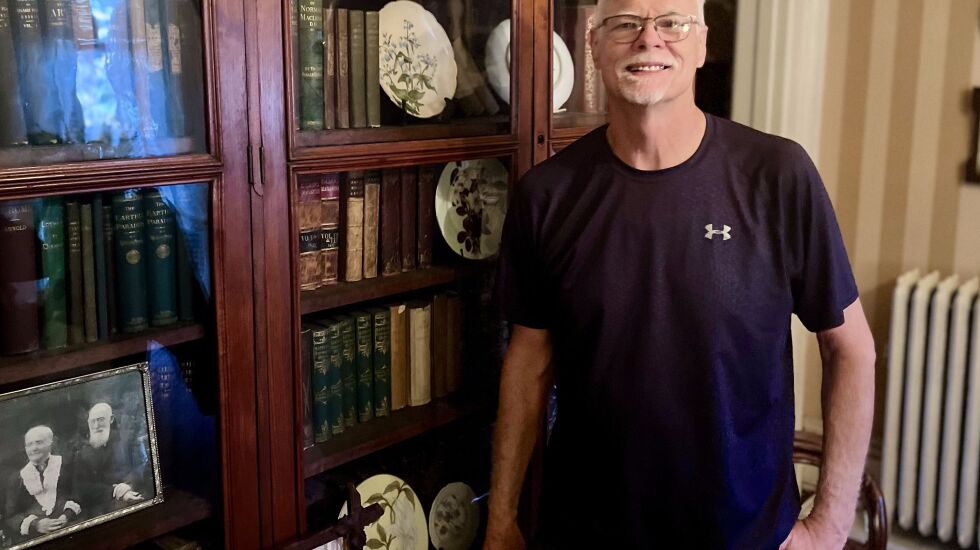

“We’ve always had a little bit of a chip on our shoulder,” Tim Weik, president of the Stephenson County Historical Society board of directors, said at the historic Oscar Taylor House.

The mansion that now serves as a museum was a known stop on the Underground Railroad.

The city also played a key role in the nation’s slavery discourse as host of the second debate in 1858 between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas, which was attended by more than 15,000 people who showed up by train.

Those railroads helped turn the city into a manufacturing behemoth, churning out everything from stagecoaches and home medicines to tires and cast-iron toys and shipping them across the nation and world.

As those industries faded into the 1970s and ‘80s, so did the train lines and the job market.

“We grew on the railroad and died a little bit with the railroad,” Weik said. “We’re kind of a difficult, sad tale of the Rust Belt. … We’ve still got good people and workers who need more opportunities.”

‘Important that we rule for ourselves’

Today, Freeport is about 70% white, 17% Black and 6% Hispanic, by the U.S. Census count, with 21% of residents living at or below the poverty line — well outpacing the statewide poverty rate of 12%.

That’s reflected in the modest workers’ cottages in neighborhoods adjacent to vacant industrial areas on the east side of Freeport but less so in the expansive estates that dot bluffs over scenic Krape Park in the southwest portion of town.

The population loss now has acute ramifications for the city. By falling below 25,000 in the 2020 Census count, voters will decide Nov. 8 whether to maintain Freeport’s home-rule status, which allows local officials to impose taxes and other fees for city services.

Home-rule opponents from the state’s real estate industry argue that it drives up housing costs by giving a blank check for local leaders to impose taxes. But supporters such as Freeport Mayor Jodi Miller say it actually keeps property taxes down because it means the city doesn’t have to look elsewhere to replace a potential 20% loss in revenue.

“It’s really a quality-of-life issue,” said Miller, who leans Republican and became the first woman elected to lead the city in 2017. “It lets us provide the services that help make Freeport a strong community and a destination to do business or raise a family.”

Mitch Ruegsegger, 39, said he’s skeptical about maintaining home-rule status because he’s skeptical of all politicians.

“The men who make the rules are usually the ones breaking the rules,” Ruegsegger said while sunning an iguana outside his Fin Fur Feather Pet Shop in Freeport.

Longtime Freeport residents Carol Morrisett and Jan Kunkle said they think home rule is vital to keeping the city viable.

“It’s important that we rule for ourselves rather than the state of Illinois. There are people down in Springfield who’ve never been to Freeport,” said Morrisett, who volunteers along with Kunkle at Amity’s Attic thrift shop.

Both are staunch Democrats, but they’re not sure either party has a solution to stanch their city’s population loss.

“Once the jobs are gone, the kids graduate, they go off to college, and they never come back,” Kunkle said. “If you figure out a solution, call me.”