While the number of Kiwis in prison is expected to decrease per capita over the next ten years, prison reform advocates are concerned by an increasing reliance on custodial remand

At 7850 people, New Zealand’s prison population is the lowest it’s been since 2008.

In its latest projections for the prison population over the next decade, the Ministry of Justice puts this down to a co-perative justice sector and a move towards therapeutic approaches.

The prison population is expected to rise slightly over the next decade, reaching 8,000 by June 2031. It’s a significantly lower projection than the 14,400 predicted back in 2017.

The report painted a rosy picture for the sentenced prison population, which at 4,900 people is the lowest it has been since 2003 and is expected to decrease over the next decade.

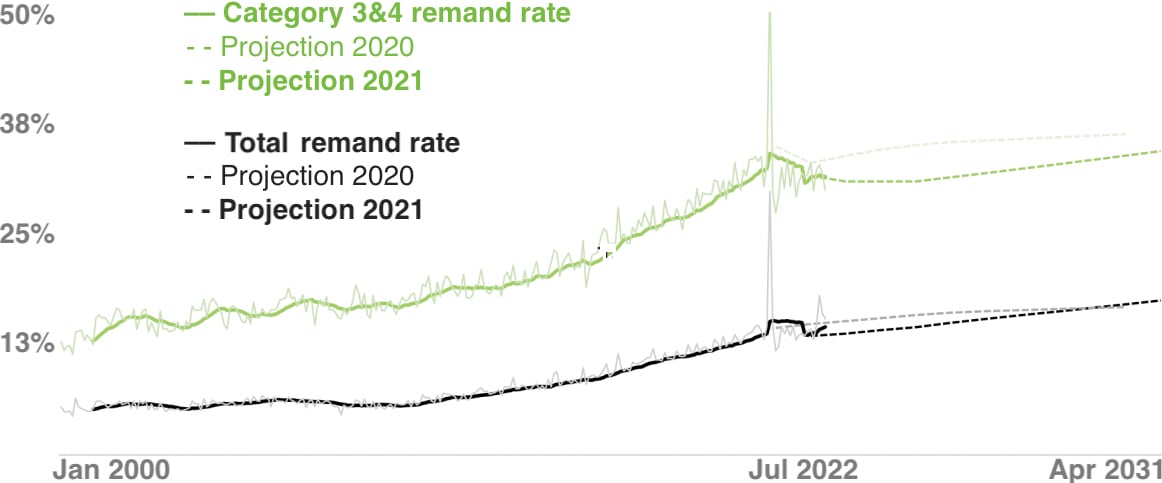

But while this is all good news, prison reform advocates and the Ministry of Justice itself have warned that growing numbers of prisoners in remand may pose a significant issue.

These are the prisoners being held in custody while they await trial or sentencing. Right now, the remand population has decreased from 4,000 at the beginning of the pandemic to just under 3,000 as of November 2021.

These lower numbers are expected to continue in the short-term, but the ministry cautioned that its expected increase over the next decade could be a factor that drives up the total prison population.

Ministry of Justice general manager for sector insights Anton Youngman said delays from Covid-19 and defendants being able to plead guilty later in court cases was contributing to prisoners spending longer in remand.

““The remand population is projected to grow in the long-term as people spend longer in remand,” he said. “Addressing these delays remains a continued focus of the justice sector. A number of initiatives are in place and additional initiatives are being developed.”

Remand is by its very nature supposed to be a temporary, in-between state, with prisoners potentially moving onto a longer prison sentence or having their time already served taken into consideration by the court.

But according to Jordan Anderson, chair of the prison reform charity JustSpeak, the intended temporary nature of custodial remand carries consequences with wide ramifications.

She said rehabilitation was harder to come by for remand prisoners, many of whom could be given community-based alternatives.,

“People on remand don't have access to programmes and that's where a lot of the Covid is spreading because of the design of the remand areas of our prisons,” she said. “As a reult, it’s not a safe place for people to be in terms of being rehabilitated as well as in terms of Covid at the moment.”

She said for the remand population to increase in proportion to the entire prison population was “really alarming”.

“Realistically, a lot of people that are on remand could be released, essentially.”

JustSpeak is calling for greater consideration for community-based alternatives to custody, which Anderson said should be a last resort. Instead, she offered ideas such as court-ordered anger management and Alcoholics or Narcotics Anonymous.

“We would like to see community-based alternatives that enable people going through the justice system to access support services that they will need in order to rehabilitate and reintegrate effectively into the community,” she said. “Custodial remand really cuts off their access to whānau, to support services, to any rehabilitation they might have been able to get on the outside.”

And if prison itself is a criminogenic space - a place that breeds further crime down the road - more people in prison becomes its own self-fulfilling prophecy.

“It isolates [prisoners] in a profoundly harmful bubble,” Anderson said.

According to the ministry’s report on the projections, an increase in the remand population could be blamed on a number of factors leading to delays in court appearances, such as increases in the rate of court adjournments, the number of days between hearings due to lack of court resources and more people electing for jury trials, which take longer to complete than judge-alone trials.

Anderson said custodial remand was also used when defendants lacked access to suitable accommodation outside prison, be it due to gang-affiliated family members or a lack of housing in general - reasons she called absurd.

“Because you have nowhere else to go shouldn't be a reason for someone to be put in prison, that's not good enough,” she said. “We have nowhere else to send you so we'll send you to the most expensive housing in the country - that cannot be the solution that New Zealand has to people in need that are tied up in the criminal justice system.”

The justice ministry says a number of initiatives are in place to try and hold back the increasing tide of remand prisoners, with more yet to be announced.

Some of these include a bail services support pilot that helps people apply for bail and adhere to bail conditions and a programme to improve the efficiency of the court system.

Youngman said projecting long-term trends across the justice sector was a challenge, and these projections weren’t an illustration of a future set in stone.

“These projections represent only one possible future, and not the future,” he said. “It’s essential that we understand what will happen under current settings so we can use it as a baseline to measure the success of future changes.”