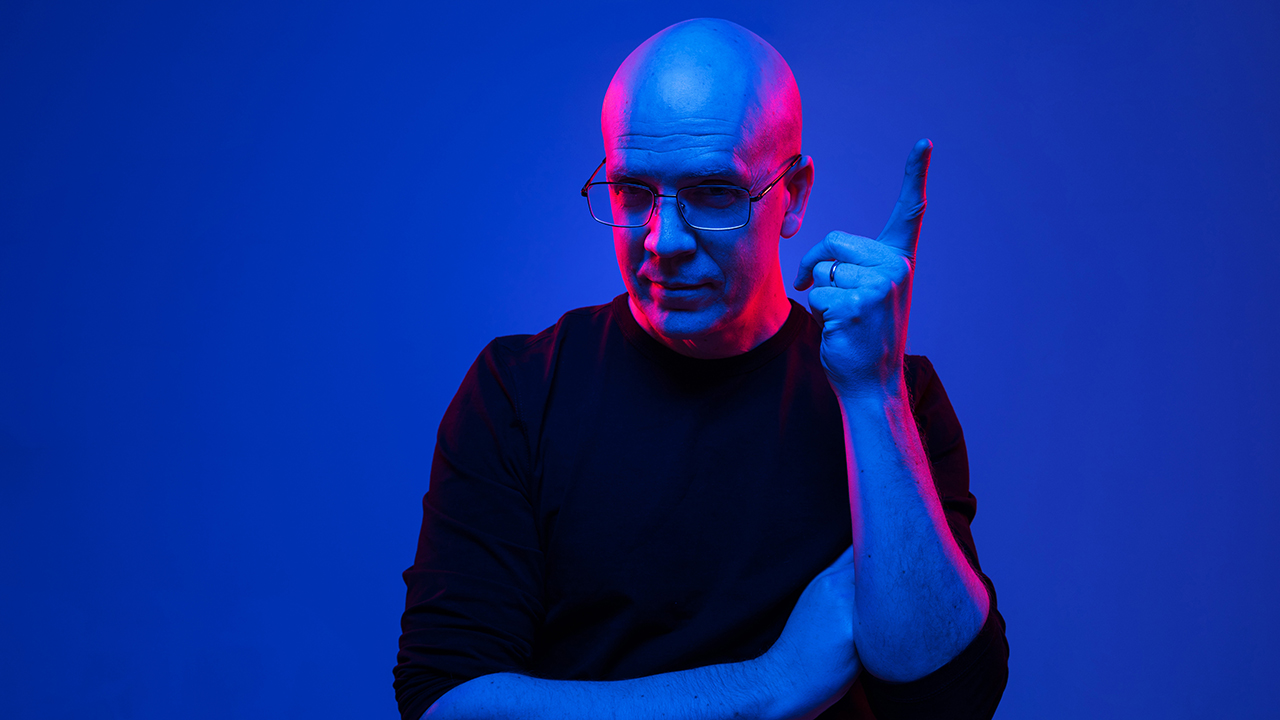

When the uber prolific, uber-talented Devin Townsend released his eighteenth studio album Empath in 2019, Prog made him the subject of The Prog Interview, where he not only discussed his then-new album but his career to date...

Devin Townsend wants to get something off his chest. For the last hour, he has been talking to Prog about his life, his career, his mental state, his view of sex and countless other things. “Can I just say thank you for taking the time to listen to me,” he says without a trace of irony when we’re done. “This process is as helpful for me and I hope it is for you.”

Where some musicians are guarded or inarticulate, the Vancouver-born singer, guitarist and leader of at least half a dozen bands over the last 25 years is the exact opposite. You get the sense that moments like this are as much a chance to work through his own thoughts and experiences as they are interviews.

But then Devin Townsend isn’t like most rock musicians. He’s both prolific and protean enough to qualify for the description of ‘maverick’. Whether it’s the mohawked brat-prodigy who rose to fame as the singer for guitarist Steve Vai in the early 90s, the confrontational presence who fronted heavyweight metallers Strapping Young Lad, the puppet-master behind coffee-guzzling alien Ziltoid The Omniscient or his more prog-friendly incarnation as the leader of the Devin Townsend Band and the Devin Townsend Project, his career has been a grand exercise in confounding expectations.

That’s exactly what happened when Townsend dismantled the Project a few years ago to pick up a solo career he’d abandoned in the late 00s. His latest album, Empath, is credited to Devin Townsend alone and acts as a journey through his entire career. It’s dizzying and disorientating, moments of brutal noise giving way to blissful soundscapes, jackhammer rhythms slipping into calypso beats.

Talking to him requires just as much concentration. A simple question about musical influences leads him off down a path that touches on artistic motivation, authenticity, the subjective nature of reality and more. It’s like a therapy session where he’s both doctor and patient, albeit one with a distinctly Canadian sense of humour and superhuman levels of self-deprecation. “Oh, I think I’m pretty mediocre at most things,” he says cheerfully at one point. “Except maybe talking, as you’re finding out.”

But then it’s those personality traits that make Devin Townsend utterly unlike anyone else out there. And anyway, if you’re going to look back over the career of one of music’s great modern day mavericks, you may as well go deep or go home.

Your new album, Empath, sounds like your entire career condensed into 75 minutes of music. Was that deliberate?

With the last band I found myself feeling, “I’m just chasing my tail here. I got nothing more to write about.” So this time I just started writing, and without having any agenda, I found that I wrote in a ton of different styles. I’ve been told throughout my career that you can’t put them all in one place. Even in my own mind, I didn’t feel you could put it all in one place because without a theme it doesn’t have an identity as a record. It ended up being congruent with the theme of the album. The whole idea of ‘empath’ as a term is referring to how I perceive my environment, how I absorb the energy of situations and of people, which hasn’t always been good in the past. So the loophole for me is the idea of Empath ultimately meaning participating in your own emotions as well as the emotions of others, which gave me a reason for once to put all these different styles in one place.

Was it difficult to get over that mental barrier?

It was one of the most difficult parts of this process. It sounds more dramatic and more romantic than it actually is but it took more bravery to make this record than I had anticipated.

Why?

Prog music, or heavy music in general, is a very conservative scene. When you are willing to expose yourself emotionally, it’s a vulnerable place to be. It’s a lot easier in a lot of ways to stay consistent, make a six out of 10 record every time, make a decent living and let it roll.

Why did you disband the Devin Townsend Project? Boredom?

Boredom was part of it. But my objectives, and why I do what I do, has less to do with music than the process of it. You want to become a better version of yourself, to be able to find compassion for yourself and others amid the brutality and the chaos of things. Everything I’ve done has existed, in hindsight, to recognise the things that I did incorrectly with them. Like, I’m obsessed with where the drummer lands on the beat, to the point where it’s caused problems with drummers in the past. By the end of DTP, it’s like, “Wow, it feels like we’re playing to a track. Back to the drawing board!” So in a sense I wanted to be creatively free. Also, I had all these guys on salary – it was, like, 20 grand a month to have that band. I was touring 11 months of the year to pay the band.

Was it scary to step away from the DTP?

Well, I’m constantly afraid but I keep doing it. I guess I’ve got to credit myself for this kind of meek courage that has sustained me through this whole thing.

Let’s go right back to the beginning. What posters did you have on your wall as a kid?

[Laughs] Loni Anderson, Christie Brinkley… I liked girls. I loved the idea of sex. I thought it was the greatest thing ever, probably because I wasn’t having it.

Okay, what music posters did you have on your wall?

I was really into the hippie, new age stuff when I was a kid. And then I heard Slade, which lead to heavy metal – Motörhead, Judas Priest…

Who was the band that made you think, “I want to do that”?

I don’t think there was ever one band that made me feel that. I was never like, “Oh, I really want to be like Judas Priest” or “I really want to be like W.A.S.P.” They influenced me for sure, but it was never, “I can’t wait to be like Blackie Lawless.” I’ve always considered what I do to be very separate from all of that. The guitar for me is a means to an end as opposed to legitimately having a connection with it. In fact, I always get invited to these guitar clinics to play with these guitar players and I’m always thinking to myself, “I’m a fraud here. I don’t know what I’m doing.”

Some men become musicians to attract women, some do it because they’re scared of them. Which were you?

That goes back to sex. I love sex, but I think I never wanted to have it. So whenever women would want to have sex with me, I would just be like, “No, no, it’s not right.” In my life I’ve slept with, like, two people. Very limited experience but I’m still obsessed by it. I think it’s down to some sense of unity. Throughout my career everything has been about dark and light. Sex was always, “Oh yeah, now it’s all coming together for seven minutes.” Well, three minutes of sex and four minutes of crying.

Let’s get back to music. When did progressive music come into your life?

I never liked the traditional prog stuff – The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway, Foxtrot, that kind of thing. What I did really like was the pop record by Yes [Owner Of A Lonely Heart]. That was a huge record for me. And Pink Floyd – they were so emotionally intense. It manipulated emotions in a way that implied an awareness of the deeper levels of existence in ways that, say, Frank Zappa didn’t. I found that be really authentic and worth pursuing. For me, my interest in progressive music was also tied in with my interest in this sort of hardcore thing that was going on in Vancouver at the time. We had bands like SNFU and Dayglo Abortions and NoMeansNo – it was punk but it was progressive. All these bands were doing things that were really interesting but they were ugly and gross and they had base humour. There was none of that blow-dried hair. The progressive scene was so clean – the bands smelled like nice soap and didn’t think farts were funny. I remember thinking, “I don’t like this at all.”

Did you fit into that scene?

Not really. I think my problem was that because I wasn’t having sex, I learned how to play guitar really well, so I didn’t really fit in with what was happening in Vancouver. And then when I ended up getting into the more progressive thing, I didn’t fit in there either because everybody thought I was kind of crass or a jackass. Which I was. Even now, I find a lot of the progressive bands are so po-faced that I still end up feeling like a jackass. I guess what I find funny isn’t funny.

You mention Frank Zappa. Were you ever a Zappa fan? You’re both mavericks…

Never a huge fan of Zappa. I love Captain Beefheart – the Clear Spot era and the Trout Mask… era and the Bat Chain Puller era. The thing I liked about him that I disliked about Zappa is I felt he was oblivious to what he was doing, and I found that really romantic. I felt that Zappa was so scientific about it that I didn’t feel any emotion from his music. There was almost a condescension to it, like: “I’m the brilliant guy.” With Beefheart, I got the impression that he thought he was writing pop songs and was confused as to why no one understood them.

What do you remember about the first time you stepped onstage?

I was 15 years old and we played in a talent show at this pub. I was the frontman, but we all decided that all the lines I’d say would be scripted, ’cos there was so much pressure. They were funny lines in our heads, but it was so stiff. I came out and I was like [puts on stilted voice], “The reason we’re instrumental is because we forgot the words.” That was hilarious backstage. Onstage, not so much. I realised pretty quickly that you should just be who you are.

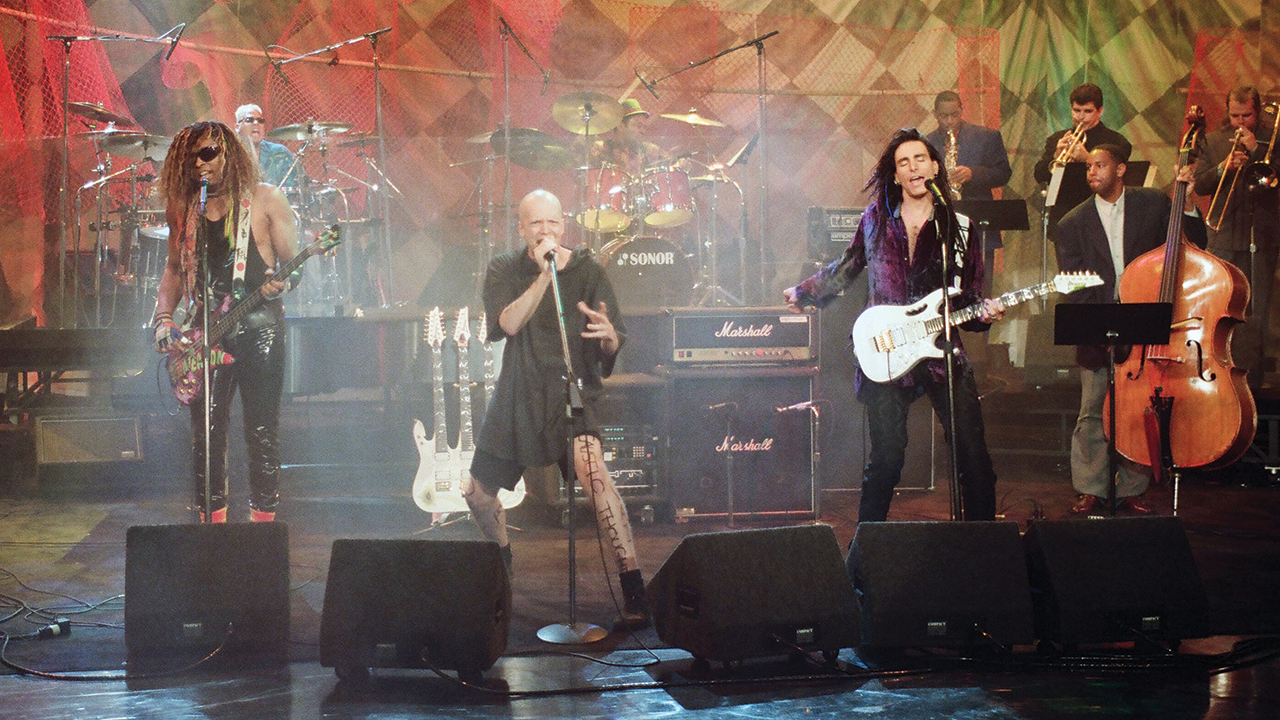

Your first big break was singing with Steve Vai’s band. What did you learn from that?

I learned that I was an asshole. I learned that my inability to express myself led me to do things just to be provocative, that I’ve just about managed to forgive myself for. But then he had just come out of an era of being legitimately a rock star and I’ve always hated that idea.

Why? Didn’t it look like fun?

No. I’m sure the rock star thing is fun to some people, but I’m not a huge fan of misogyny. I’m not a huge fan of a lot of the things that you have to suspend – the main one being that sense of hierarchy. The rock star thing is like you are fundamentally more important than the audience, than the crew, than the bass player, and that manifests as a type of personality trait that I just fucking hate. Back in the day Steve and I were antagonistic towards each other but I don’t think I was a dick to everybody. I think I was confused. I don’t think I’ve ever been, like, a bad person.

You had some well-documented mental health problems in the late 90s and early 00s, around the time you were in Strapping Young Lad…

I was diagnosed as manic-depressive after a really heavy manic episode. The mental health clinic have a list of criteria that if you fall under the umbrella of seven of 12 these criteria, which I did, then the diagnosis is, “Okay, bipolar. Here’s a type of medication that you can go on either indefinitely or until the symptoms wear off.” I was in a mental health institution for a long period of time – over two years. At the time I think I dug it – it played into this illusion of the tortured artist.

Do you buy into the idea of a link between mental illness and creative genius?

I’m in no way saying I’m a genius, but yes and no, a lot of artists find it romantic to be tortured – they’re locked up in a gallery, fighting their demons, cutting their ear off. I think ultimately everything in your life is a choice on some level. Unless you’re stricken with something that genetically you have no control over, like schizophrenia, you have the capacity to not have to suffer through that.

Didn’t you dabble in psychedelic drugs as well?

Yes, at the age of 23 I started doing psychedelics drugs. This was before I was in the mental facility.

Did that help your mental state?

Well, it helped in the long run. But at the time I didn’t have the support network to help me interpret that experience as, “It’s not you who is the centre of the universe, everything is the centre of the universe.” I took a bunch of acid and tied my hands and feet up and put myself in a closet for 12 hours, and then I’m like, “Everything’s physics!” I remember during [his 1998 solo album] Infinity, eating a bunch of mushrooms and then doing a bunch of interviews and saying just stupid fucking druggie shit. I thought I knew it all. But then I ended up hurting a bunch of people that I was close to and also hurting a bunch of people that had some investment in thinking I had answers.

That probably seemed like a good idea at the time.

Yeah. But by really fucking up – not just in a subtle way, but in a profoundly like, “You asshole” way – it took me years to forgive myself.

In the last 20 years, you have done albums as Strapping Young Lad, Devin Townsend Project, The Devin Townsend Band and Casualties Of Cool, plus two separate stints as a solo artist. Where does that prolificness come from?

My dad went broke when we were teens. I saw how he suffered as a result of that, and my mother. And I thought, “I do not want that to happen.” There was a creative impulse, absolutely but it was so military: “I am going to be creative because I’m not going to let the family suffer.” But you hit a wall. And I hit a wall and I had to sit with the management and be like, “This is the reason I am doing this.”

When was this?

About a year and a half ago. [Laughs] I started going on vacations.

How did that feed into Empath?

Oh, a lot of what Empath is about is going on vacation. Seriously. There’s all these monsters and brutality, then suddenly the music stops and you’re on the beach. That was a totally conscious thing. I go down these rabbit holes and then I’m, like, “Dude, take a deep breath. It’s not worth it.”

Can we talk about Ziltoid? There’s an argument that the whole puppet side of things distracts from the music…

I can see why people do that. But that’s my sense of humour. Why do I pull faces in photos? Because I don’t know what else to do. It’s a self-consciousness thing. I feel so self-conscious that I totally over-compensate. But I also think that people

don’t have to listen to it or even register it.

Do you set out to deliberately confuse people, whether that’s with Ziltoid or Empath or your career as a whole?

No, never. I’ve found that what ends up happening with that is that the interpretation that people have of you is selective, and in a certain way you’re always kind of on amber alert because you have to protect this persona that you’re strategically allowing people to see. Empath is different – it’s just like, “Fuck it, whether or not it’s acceptable whether or not this loses half of the fan base.” So much of my process is rooted in fear.

You’ve been doing this for more than 25 years. Fear of what?

Fear of participating in life in an authentic way. When I was younger, the upbringing that I had was very stiff upper lip. Overt displays of emotions were frowned upon, yet because I was highly sensitive and have been since birth, it’s been this weird thing that music has become a place where I can channel those feelings into. But what it also ends up doing is creatinga facade of who you are – this exaggerated, Photoshop version of your identity. It’s me, but just a little better. But then you’re always conscious that thatmmight just be full of shit and not authentic.

What’s so important about authenticity?

Following the muse is about trying to find truth on a fundamental level, and I think that in searching for truth, if you’ve created a version of yourself that you know in your heart is not completely authentic, what ends up happening is you participate in your emotions intellectually as opposed to as a human.

Empath… Ziltoid… The Devin Townsend Project… Casualties Of Cool… Strapping Young Lad… which one is the real Devin Townsend?

They all are. And none of them are, I guess. It’s impossible for me to say. Does anyone truly know who they are? I know I don’t.

What have you learned?

What, from this interview? Lots. From life? I’ll get back to you on that.